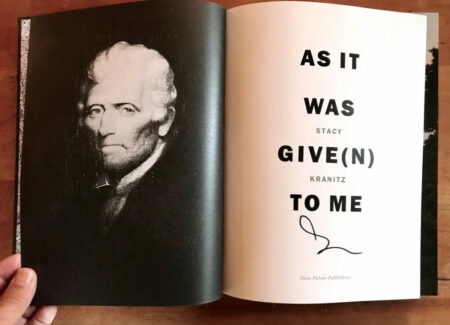

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2022 by Twin Palms Publishers (here). Clothbound hardcover with foil-stamped lettering, 9 x 11.5 inches, 204 pages, with 225 color photographs and numerous drawings by the artist. Design by Jack Woody, Kevin Messina, and the artist. In an edition of 3000 copies. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: The American photographer Stacy Kranitz is closely identified with Appalachia, but the path to that association has been circuitous. She was born in Frankfort, Kentucky, in 1976, the same year Barbara Kopple released the documentary Harlan County, USA, based just down the road. Inspired by the children’s novel Harriet the Spy, Kranitz began documenting her life at an early age, filling notebooks with observations about friends and neighbors. She grew up in several states, including Tennessee, Florida, California, and Oregon, where she was involuntary enrolled in a wilderness education school. She spent time in Louisiana, attended NYU for undergrad, then circled back UC Irvine (her teen haunt) for her MFA. At loose ends afterward and living out of her car, she rekindled her Appalachian roots, eventually settling in Smithville, Tennessee, near her mother’s childhood home.

Smithville is in eastern Tennessee, along the western slope of the Appalachian range. A page on Kranitz’ website called Location includes a map of the area with driving times to regional cities. It shows much of central Appalachia within a half day’s journey. The proximity is by design. “I cover middle America, the deep South and the Appalachian region of the United States,” the page explains, “for editorial clients including: Bloomberg Businessweek, ESPN, Mother Jones, New York Times, Time, Vanity Fair and the Washington Post.” In other words, Kranitz has cultivated access, skill, and family heritage to position herself professionally as a hired gun and regional authority, at least as viewed by media companies.

But it’s not just editorial gigs which connect Kranitz to Appalachia. For the past dozen years, she’s been working on the long-term personal project As It Was Give(n) To Me, a multi-pronged photographic exploration of Appalachia. Kranitz has been engaged off and on with AIWGTM for much of that time, making photos as her schedule allows, exhibiting them regularly, and even publishing an early edit in a 2016 chapbook called Speak Your Piece (titled after a newspaper column which I’ll get to in a moment). The final goal was always a major monograph, but the finish line was elusive. AIWGTM kept growing and shifting, ever more unwieldy and daunting, the monograph pushed continually into the future.

Until now that is. Spurred by her 2020 Guggenheim fellowship, Kranitz teamed with Twin Palms to finally wrangle As It Was Give(n) To Me into published form. As might be expected, her magnum opus is a beast, weighing in at four pounds and 300+ pages. The first encounter is overwhelming, and might be impenetrable if presented en tout. Fortunately the material is broken down into five manageable chapters. Their sequence follows the rough order of white western expansion into Appalachia: Arrival, Exploration, Extraction, Mutiny, and Salvation. If it also critiques the trajectory of parachuting photojournalists, that’s an added bonus.

As one can probably tell from the headings, Kranitz takes a dim view of manifest destiny. Hers are not cheery photos and AIWGTM is not a cheery book. The title might refer to tales of settlement as passed down in misleading history books, or to the actual land grabs, or perhaps something else. After browsing its rather downcast imagery, I’m tempted to draw links between chapter headings and the five stages of grief: Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression, and Acceptance. There appears to be some crossover, but I admit the connection is speculative, and it’s unclear if Kranitz intended any correlation.

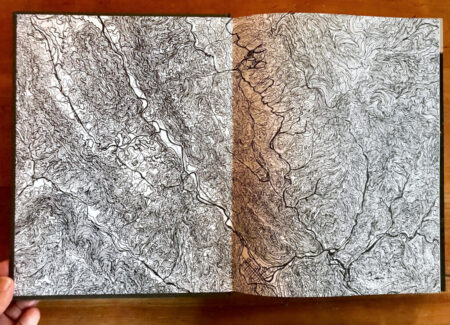

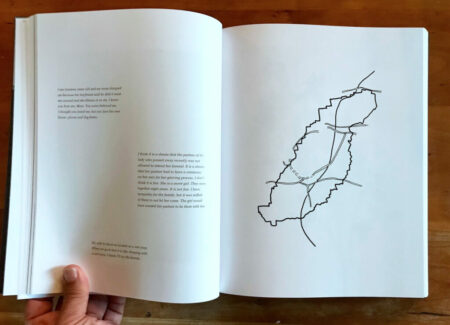

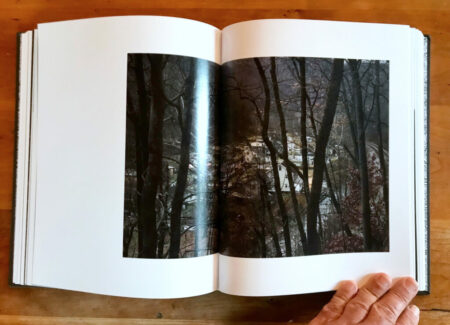

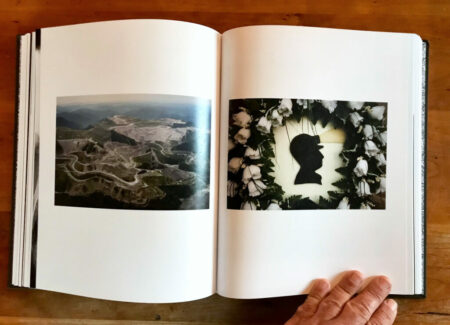

As It Was Give(n) To Me is a regional study, strongly rooted in place. Provincial cues begin immediately with the cover graphic and end pages, which show topographic maps of Appalachia drawn by Kranitz. The lines are tight, depicting incredibly steep relief. They feel closer to a fingerprint than a physical location. Even if Kranitz has perhaps taken poetic license with the illustrations, their implication is clear: Appalachia is a land of precipitous hills and hollers, lined with twisty drainages and scant flat territory. These facets are crystalized in the book’s opening double spread, a broad landscape of rural hills draped in fog. A few ridges poke above the white. Most of the territory’s secrets remain buried underneath.

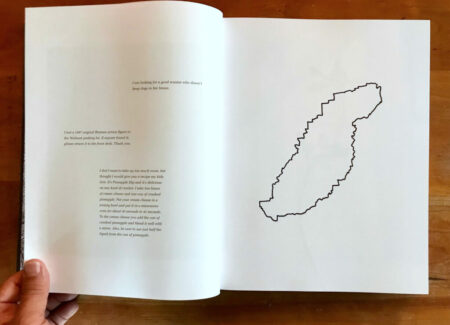

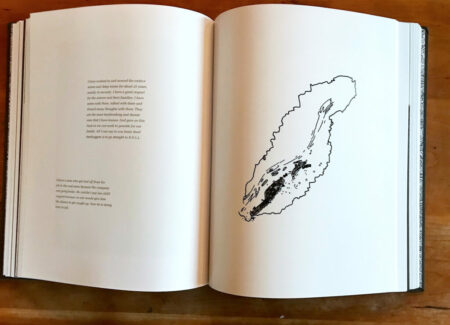

On the following page, the opening section Arrival sets the framework for the book’s structure. It begins with a monochrome reproduction of a cropped Daniel Boone painting, facing the chapter heading across the spread. Several photographs follow, then a break for text passages and a schematic map of Appalachia, as drawn by Kranitz with shifting impact patterns imposed. We see a spider web photographed against a black background, a nod to deep entanglements and local fauna.

The texts, spaced across several pages, are excerpted from the weekly column “Speak Your Piece”, published in the Mountain Eagle Newspaper in Whitesburg, Kentucky, from 2009 to 2021 (roughly the timeline of Kranitz’ photos). The original presentation is unknown, but in the book they’re anonymized and culled into barbed commentary, sampling a range of views and issues, touching on everything from daily encounters to political opinion to long-simmering grudges. Most are quite poignant, and correlate in general way with the surrounding photos. But they reach a part of the reader’s brain quite distinct from the photo receptors.

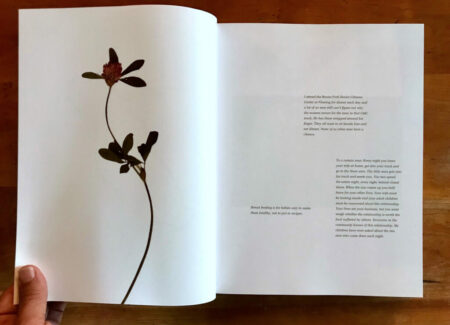

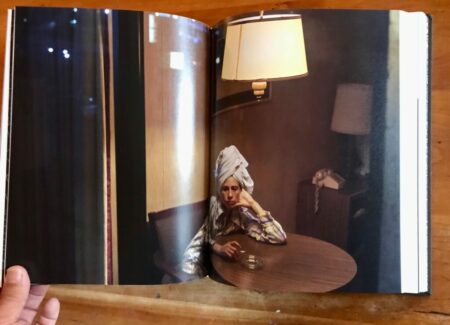

Capping the “Speak Your Piece” sections, some of the quotes are accompanied by one or two photos by Kranitz of pressed plants and flowers. “I made this book that was like a cure for depression,” Kranitz explained in an interview. “So now I continue to press flowers and I often do it when I’m feeling stuck. It keeps me engaged in the landscape.” The plant images are followed by dozens more photos, before each chapter ends in the same way: with a photo of Kranitz role playing a local character, shot by one or another of several photo friends, and seemingly well integrated into the gloomy fabric of Appalachia.

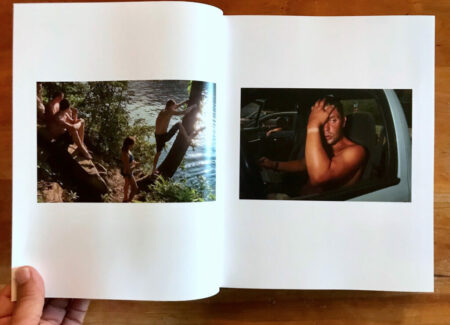

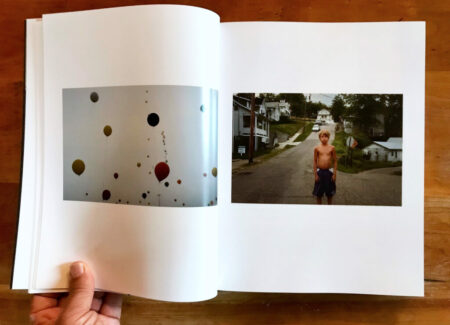

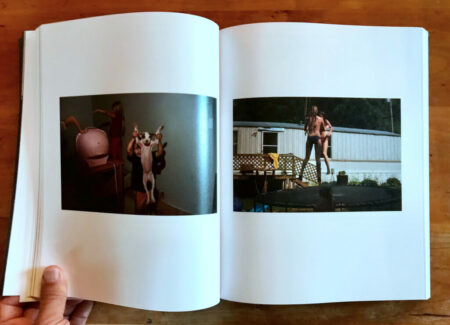

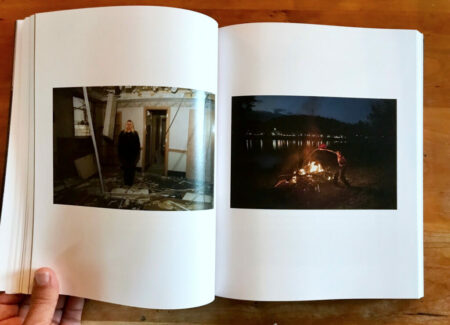

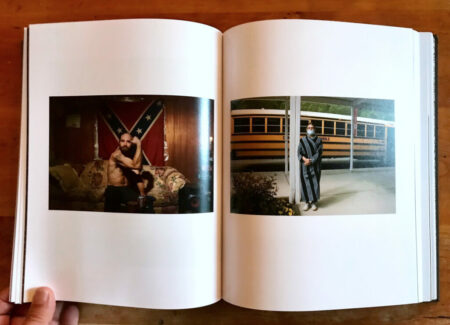

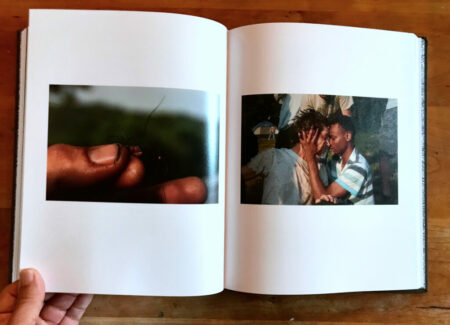

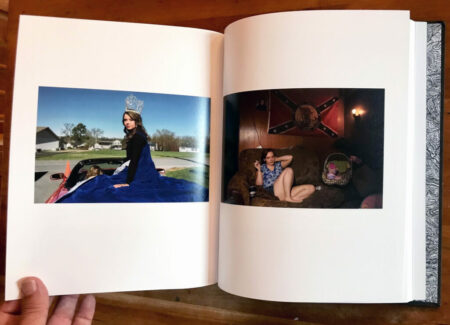

Each chapter assumes this rough structure. But they are merely the framework. The meat of the book is comprised of Kranitz’ pictures. They cover a range of subject matter but her primary interest is humans and their curious rituals. Some frames can be loosely categorized as portraiture, depicting people in their environment gazing back at Kranitz with even-handed attention. A bus driver in her morning bathrobe peers out at us over her Covid mask. A young beauty queen looks bored staring back from her chair.

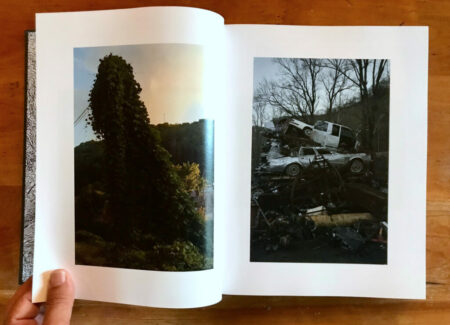

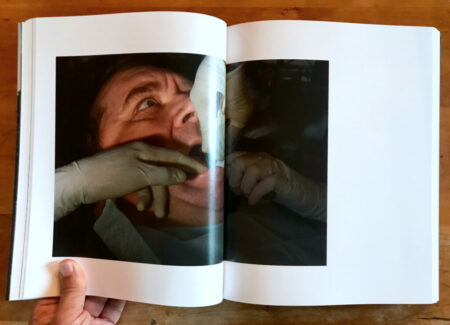

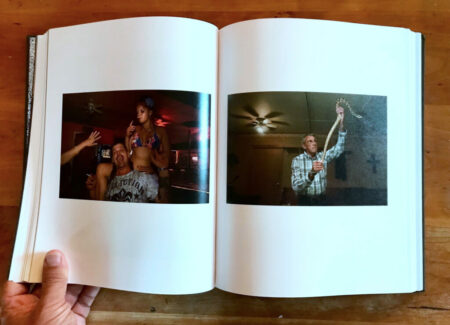

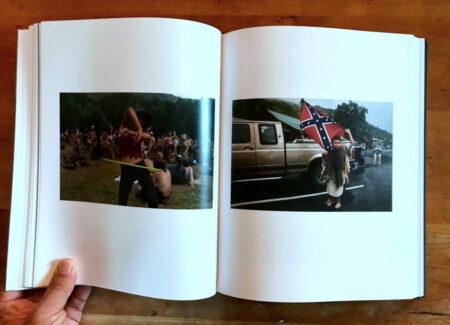

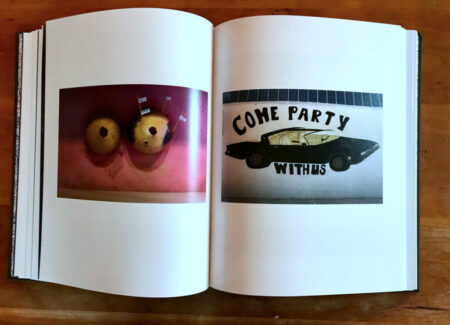

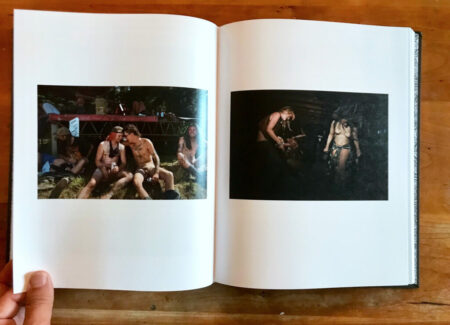

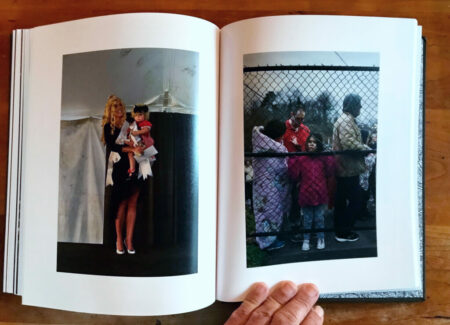

These still frames take a stab at Appalachian culture, but they aren’t the main event. Where AIWGTM really picks up speed is in photographs of active engagement. Kranitz seems to relish immersion and interaction, catching subjects candidly consumed in daily life. She photographs church revivals, strip shows, festivals, swim holes, parties, smoke breaks, and more. When there are no people around, she documents housing or town corners (one such scene bears an uncanny resemblance to the original Uncommon Places cover shot). All in service to the bigger picture: Appalachian ritual. What do people do there? What is it like? Well, here’s one impression, at least as it was give(n) to the reader.

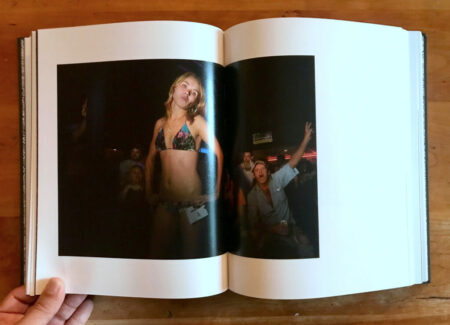

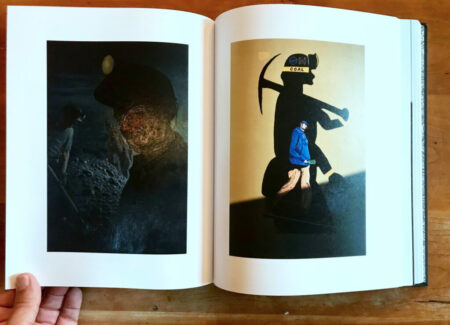

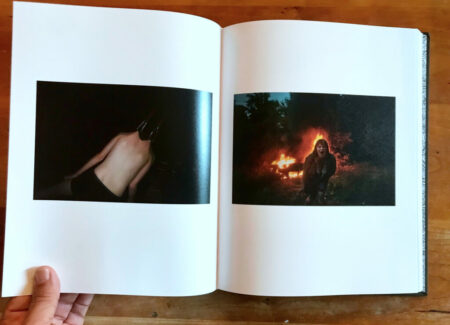

Dark undercurrents surface regularly—e.g. Confederate flags, snake handling, junkyards, coal-blackened miners, and enough individual cigarettes to fill a few packs. No single picture is too much over the top, but collectively they contribute to a simmering tension which builds for three chapters until finally boiling over in the book’s emotional crescendo: Mutiny. It’s worth noting that the photos in this chapter were not initially part of the book. They were incorporated at Jack Woody’s suggestion from Kranitz’s tangential project “From The Study On Post Pubescent Manhood”, which she shot while living in a dystopian compound in rural Ohio called Skatopia. “I went there searching for displays of violence that function as catharsis,” she writes, and by all appearances she found it. Mutiny captures young ruffians in all manner of debauchery, burning cars, caked in mud, bleary eyed, grasping at dirty panties, hanging from meat hooks, fleeing flames, and carrying on. The final photo shows Kranitz having sex with a man in a basement laundry room.

Is this an accurate description of Appalachia? Well, yes and no. As with all so-called documentary photos, Kranitz’s are a translation of reality as found, but only to a degree. Kranitz acknowledges the inherent subjectivity of the genre with open skepticism. “Working within the documentary tradition Stacy Kranitz makes photographs that acknowledge the limits of photographic representation,” she explains on her website, before adding that “her images do not tell the ‘truth’ but are honest about their inherent shortcomings, and thus reclaim these failures (exoticism, ambiguity, fetishization) as sympathetic equivalents in order to more forcefully convey the complexity and instability of the lives, places, and moments they depict.” In other words, As It Was Give(n) To Me is intended more as mythology than raw evidence. These photos might bear roughly the same relationship to reality that Daniel Boone has with later glorified depictions of him. That is to say, tenuous.

In the current post-truth era, Kranitz’ stance is no longer an outlier. It’s difficult for any photographer to claim fly-on-the-wall objective purity. But Kranitz takes things a step further than most by injecting herself into the material. Not only is her methodology participatory, she appears several times in this book. “I am very interested in the erasure of the distinction between my personal life and my professional life,” she explains. “I live and breathe my art, and that’s how I have always wanted it to be.”

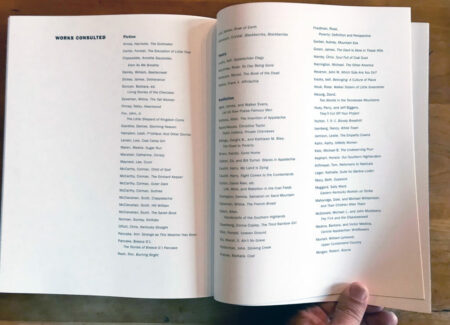

A rear index in the book called “Works Consulted” signals Kranitz’ involvement and dedication, listing books, essays, films, music, and photos which she researched as background information. Kopple’s Harlan County, USA is listed, along with Appalachian mythologists like Hazel Dickens, William Gedney, and Chris Offutt. Each has contributed to the region’s self-understanding, even if in admittedly subjective ways.

Kranitz’ process might herald a new photographic approach. But her photographs seem to reinforce Appalachian tropes. Rural communities appear tired and worn before her lens, inhabited with muscle cars, peeling paint, and laundry lines. Smiles are outnumbered by litter. Bored kids bike shirtless near railroad tracks. We may be a few generations advanced from the tar-paper shacks of Walker Evans and Marion Post Wolcott, but in some ways not much has changed. “Since Lyndon B. Johnson announced the War on Poverty in 1964,” Kranitz told Huck Magazine, “photographers have portrayed Appalachia as the poster child for American poverty.” It’s a cruel irony that her book seems to follow stereotype. Perhaps her intention is to highlight continued economic woes, and bring attention and relief. If so, great. More power to her. But considered in purely photograph terms, her depiction seems alarmingly conventional. These pictures are incisive and entertaining, but unlikely to alter preconceptions.

One aspect of publication which is not conventional is Twin Palms decision to supply 50 copies to various Appalachian libraries, in the counties where Kranitz shot the photos. “Making an expensive book about poverty is inherently problematic,” she says, a statement which might apply to broad swaths of photoland. For a book which lists at $85, Twin Palms’ donation is significant. In some communities it may mean the difference between seeing this book in person, and never encountering it. The gesture embodies the title As It Was Give(n) To Me in a simple overture which lives up to the book’s last chapter: Salvation.

Collector’s POV: Stacy Kranitz is represented by Tracey Morgan Gallery in Asheville (here). Kranitz’ work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.