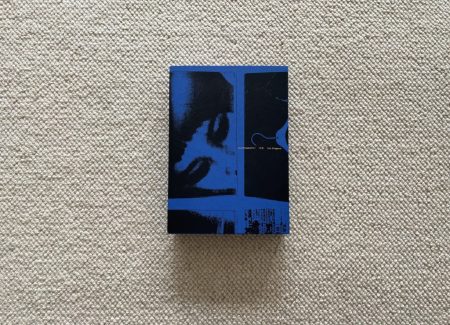

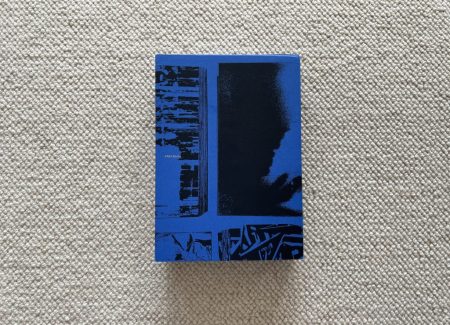

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2021 by Area Books (here). Softcover with paper jacket (black print on either blue/green paper), 150×210 mm, 800 pages. Includes an artist statement in English/Japanese on a separate card, with a list of zine/project titles. In an edition of 250 copies. Design by Bureau Kayser/Colin Doerffler. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Photo zines are an under-appreciated method for delivering photography to an audience, and as a genre, they deserve far more respect and attention than they generally receive. Zines can be designed, produced, and circulated inexpensively, making them a perfect vehicle for risk taking, experimentation, and the exploration of smaller projects. Art students, emerging artists, and others who want to take a contrarian stance to the larger photography establishment have all embraced the guerilla effectiveness of zines, turning them into an underground phenomenon. Often published in small hand-crafted editions, they seem to appear and vanish with striking rapidity, influencing those who are lucky enough to come across them.

For roughly the past 15 years, Koji Kitagawa has been an impressively prolific zine maker. Working on his own, and in conjunction with Daisuke Yokota and Naohiro Utagawa in the SPEW collective, Kitagawa has been seemingly incessantly busy with photographic experiments. Leveraging the simplicity of the zine form, he has obsessively cranked out dozens of thin publications, constantly experimenting with both process ideas and visual approaches.

For those in the United States and Europe, following Kitagawa’s efforts from afar hasn’t been easy, as the zines he’s making come and go so quickly. One more durable solution to this ephemerality has been recently provided by Area Books, in the form of a dense compendium of Kitagawa’s zines gathered together in one anthology. The modestly titled Photography brings together the contents of a total of 29 of Kitagawa’s recent zines, in a thick brick of a book weighing in at some 800 pages. As aggregated evidence of Kitagawa’s almost manic zine-making, it’s a valuable reference volume, literally overflowing with concentrated ideas, tests, trials, and inquiries.

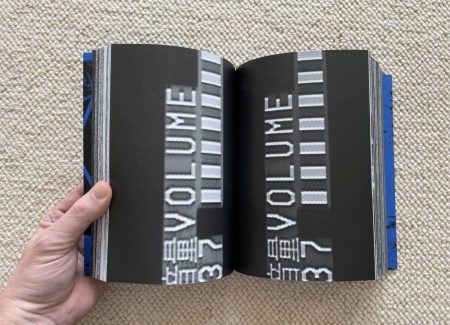

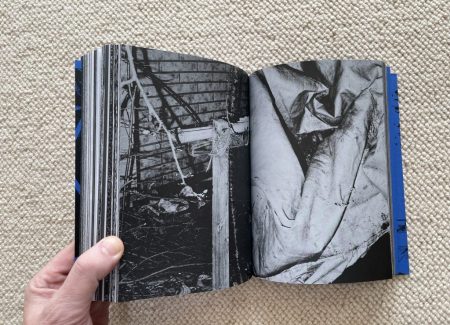

In Photography, Kitagwa’s zines are literally shown end to end, with only a few white pages here and there to provide a separation; in general, they flow from one to the next in an endless series. And while a list of the zine names is provided at the end of the book, no identifying names are found within the flow of the imagery, so it’s nearly impossible to be entirely sure which titles refer to which bodies of work.

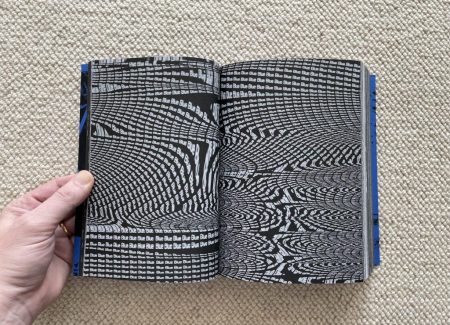

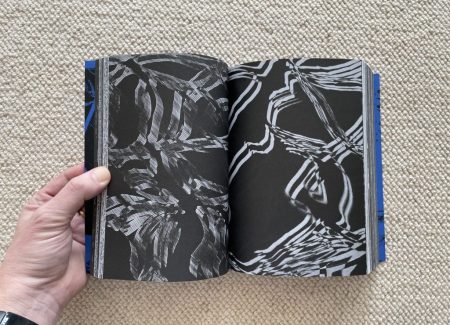

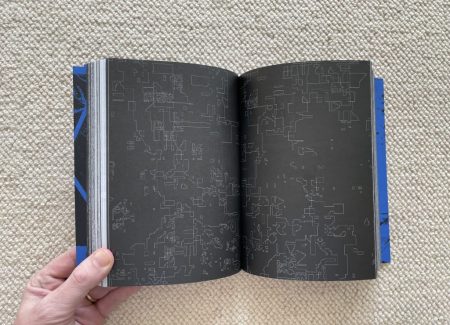

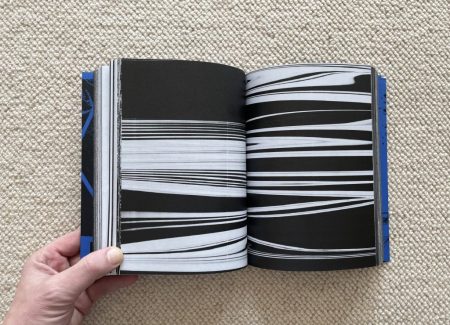

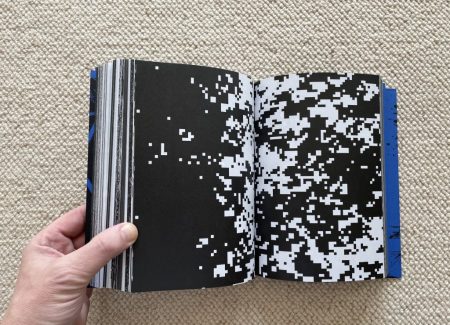

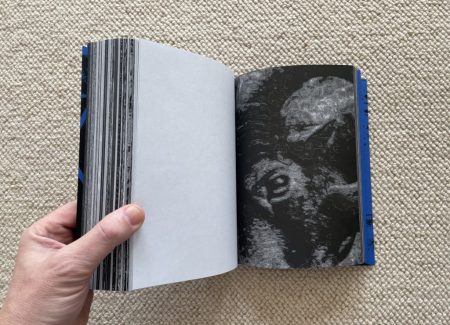

Many of the projects engage with themes of visual technology and digital graphics, exploring how those systems break down when they are intentionally distorted or deconstructed. In one series, the typed word “blue” fills an entire screen, only to be warped, twisted, and morphed into a nearly unrecognizable abstraction of smeared letters. In others – which are all constructed from abstract technical or computational motifs – stripes twist and dance; thin blocky patterns build up and recede; high contrast horizontal lines create changing striations; and black and white pixels aggregate and disperse. And in one mysterious sequence, an image of a goat iteratively dissolves into digital texture, the enlarged fragments of the picture becoming increasingly unidentifiable, almost like a shifting topographical map.

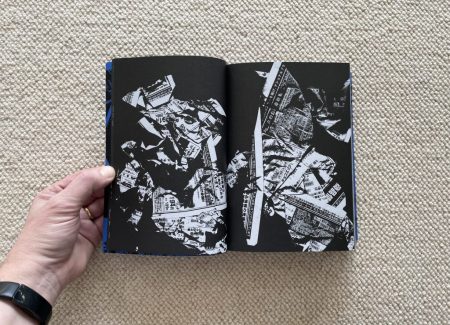

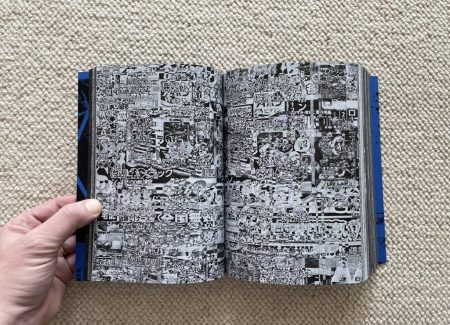

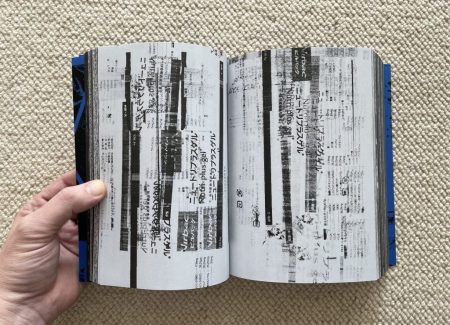

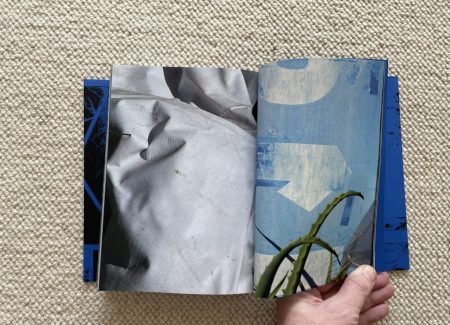

Paper and layered photocopying form the basis of several other innovative projects. Crumpled and torn pages of Japanese advertisements open the anthology, with each page turn leading to yet another formal twist and rework of similar content, the text patterns and graphics bent, folded, and smashed into new sculptural shapes. Dense layers of Japanese graphics pile up in another sequence, becoming more and more illegible with each iterative layer, almost like a hopelessly interwoven carpet of numbers and characters. And in third series, layered photocopies of ingredient information (some for a mysterious Nutri-plus gel) become increasingly ghosted and overlapped, again to the point of breakdown. In these and other projects like them, Kitagawa is exploring the ephemeral edges of visual legibility, testing how aggregation and reformatting change the nature of printed information.

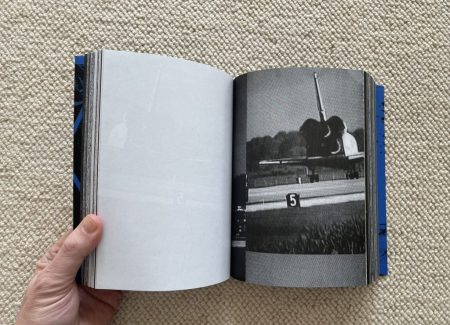

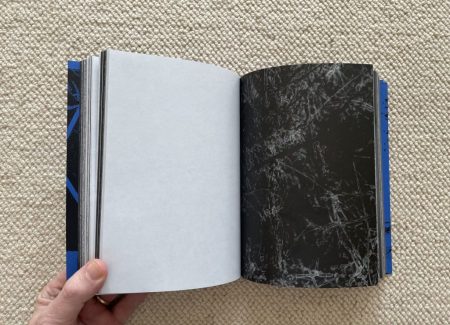

Although it is difficult to be entirely sure about what kinds of approaches, methods, and processes Kitagawa is employing in his zines, several of the projects seen to be activated by chemical washes that create surface drips, pools, and dislocations on top of the imagery. In one series, a single image of the space shuttle on a runway (perhaps as seen on a monitor?) has been multiplied out into a sequence, with each image covered with different arrangement of wet veiling. In another, various images of thickets of underbrush are set in dialogue with one another, some with negative reversals, others with what looks like areas of solarization. A dated round speaker or intercom provides the subject matter for a third series, again with each sequential picture interrupted by different kinds of darkroom drips and flares.

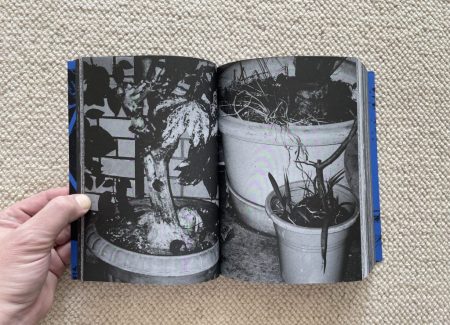

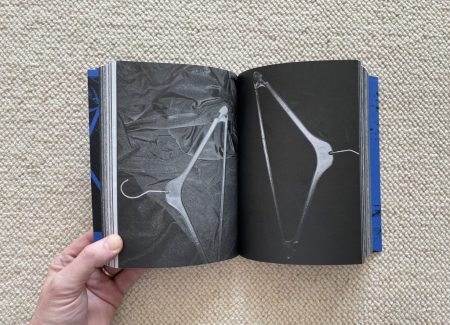

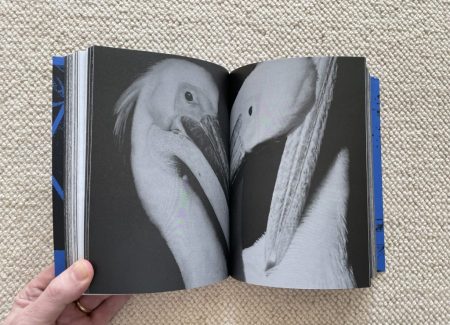

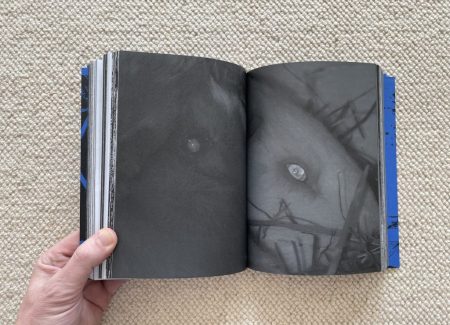

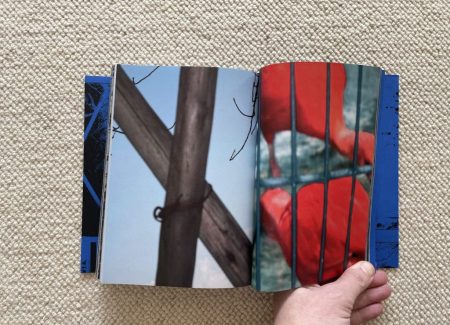

Even when Kitagawa is making straight photographs, he seems to be constantly looking for patterns, sets, and repetitions. He shows us sequences of plants in planters, plastic hangers set against black cloth (like specimens), pelican beaks, glowing animal eyes (rabbits, or some other furry creatures), and an intermingled mix of textures consisting of woven bags, nets, and various leaves and branches. Near the end of the book, Kitagawa switches from black-and-white to color, offering us a parade of formal discoveries and pairings enlivened by bright splashes of color, almost as if he was reteaching himself to see yet one more time.

If there is a through line through all of these very different projects, it is a commitment to generating deliberate ambiguity, and to the possibilities that can emerge by encouraging systems to devolve. As seen in his zines, Kitagawa is clearly a smart photographic risk taker, who is willing to actively push on the edges of photographic convention. While an anthology-style survey like this one materially changes the dynamics and feel of the original zines, it provides the important service of both archiving much of his output (over this recent period) and delivering it in a sturdier format. Kitagawa deserves to be much better known here in the United States, so hopefully this well-produced volume will broaden the universe of those who are aware of his systematically obsessive photographic mind.

Collector’s POV: Koji Kitagawa does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time, so interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artist via his website (linked in the sidebar).