JTF (just the facts): A total of 67 works, variously framed and matted, and hung against light grey walls in the main gallery space, the entry area, and the book alcove.

The following works are included in the show:

- 5 chromogenic prints, c1955/later, 1958/later, c1960/later, 20×16 inches (or the reverse), in editions of 10+3AP

- 42 gelatin silver prints, c1946, c1947/c1970, c1948/c1970, c1950, c1950/c1970, c1951/c1970, 1950s/c1970, c1952, c1952/c1970, c1953, early 1950s, 1954/c1970, c1954/c1970, 1954/later, 1970s/c1970, n.d./c1970, sized roughly 2×2, 4×3, 4×5, 4×6, 5×7, 6×9, 7×5, 7×9, 7×10, 8×10, 9×6, 10×8, 11×14, 12×8, 13×8, 14×11 inches

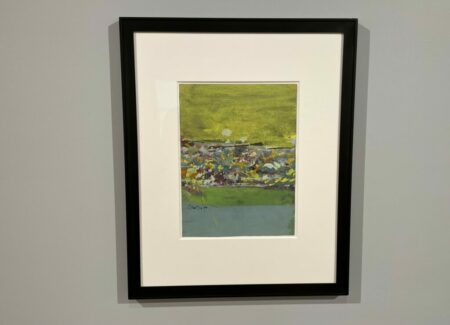

- 7 gouache and watercolor over gelatin silver print, 1972, 1973, 1970s-1990s, 2001, n.d., sized roughly 4×3, 5×5, 7×7, 8×6, 8×10 inches

- 2 Fujicolor Crystal Archive prints, 1957/later, 1960/later, 20×16 inches, in editions of 10+3AP

- 5 gouache and watercolor on paper, n.d., 2003, 7×5, 9×12, 10×7, 11×9, 12×8 inches

- 4 chromogenic prints, 1959/later, 1960/later, 1961/later, 1962/later, 14×11 inches, in editions of 20+2AP

- 2 gelatin silver photobooth strips, n.d., sized roughly 8×2 inches

(Installation shots below.)

A monograph celebrating the artist’s centennial has also recently been published by Thames & Hudson (here). Hardcover, 10.4 x 12.3 inches, 352 pages, with 340 reproductions. With contributions by Margit Erb, Michael Parillo, Michael Greenberg, Adam Harrison Levy, Lou Stoppard, and Asa Hiramatsu.

Comments/Context: Over the past two decades or so, we have been patiently introduced to the work of Saul Leiter, bringing him from a point of relative artistic obscurity to a more defined spot in the history of 20th century photography. Between monographs published by Steidl (and others) and gallery shows by Howard Greenberg Gallery (and others), the Leiter backstory has been methodically unfurled over the years, starting with his best known color work from New York in the 1950s and 1960s, and filling out the arc of his art making to include black-and-white street scenes, intimate nudes, fashion work, and overpainted photographs and watercolors. In many ways, Leiter’s story provides a smart case study of how the right support (including that provided by the artist’s estate) can meaningfully influence how an artist’s reputation is built and maintained.

Starting roughly a decade ago, initial retrospectives of Leiter’s career started to appear at various smaller venues around the world, and now on the occasion of the centennial of his birth, a fuller retrospective volume has been published, led by the artist’s estate. This gallery show hits its mark in terms of coinciding with the publication of the heavy tome, but it isn’t really designed to mimic the scale, scope, and depth of the 300+ images reproduced in the book. Instead, it offers a quick survey of Leiter’s multiple subject matter areas, and in this way, it hits the tops of the waves of his career with what’s still available for sale (including both vintage and later/posthumous prints), as opposed to delivering a comprehensive summary, which would have required linchpin loans and more supporting scholarship.

Leiter’s photographic fame is largely tied to his use of color in New York street scenes made in the 1950s and early 1960s, and a handful of these images provide the structural scaffolding of this installation, with large single images sprinkled through the proceedings here and there. He found particular inspiration with the arrival of snow and rain in the city, where wet windows and dripping condensation offered impressionistic possibilities for blurring and distortion. Against the drab backdrop of the greys and blacks of the winter, Leiter introduces pops of color – a yellow taxi, a red umbrella, the brightness of street lights – which seem all the more unexpected when set off by the cover of white snow. Compositionally, he was constantly experimenting, with shots framed from inside cars and shop windows, layered by reflections, or unbalanced by the intrusion of a dark awning. Another image plays with layers of lettering and echoes of red (featuring a red truck and a red necktie), and Leiter then bridged these kinds of techniques over into his fashion work for Harper’s Bazaar (as seen in a group of images hung in the gallery’s book alcove), where models are staged within interrupted color stories and disrupted flattened depths.

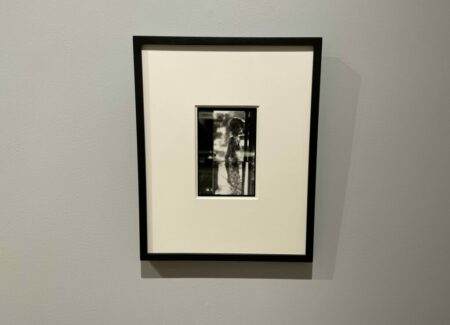

When working in black-and-white, Leiter was employing many of the same framing and organizational techniques, and the show features many examples of his monochrome efforts in the streets. A walk through New York seemingly offered Leiter endless compositional possibilities – window reflections and mirroring; silhouetted forms (both bodies and architectural features, like street lights); cloudy steam interruption and mood setting; views through wet windows; and signage and letter forms that could be cropped and reimagined. Several of the images on display also highlight the way he was actively playing with viewing angles. Leiter looks through ironwork railings, down at the sidewalk below from fire escapes and elevated train platforms, from low angles at feet, and set up behind figures on the street, turning them into anonymous protagonists in tiny vignettes and stories.

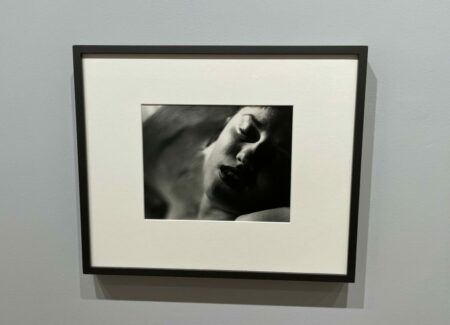

When Leiter moved back indoors, the mood changed significantly, as did his approach to making photographs. In both portraits and nudes seen here (in an echo of a 2018 show at HGG, reviewed here), Leiter settled into a much more intimate zone, where his interactions and setups feel posed but elegantly relaxed. Working in black-and-white and liberally playing with dark enveloping shadow, most of Leiter’s women seem caught in a moment of repose – sitting with a cup of coffee, at the breakfast table hiding behind a teacup, curled up on the bed, or reclining with knowing ease. Light washes across faces and draped arms, with folded limbs and other turned and touched gestures given extended attention.

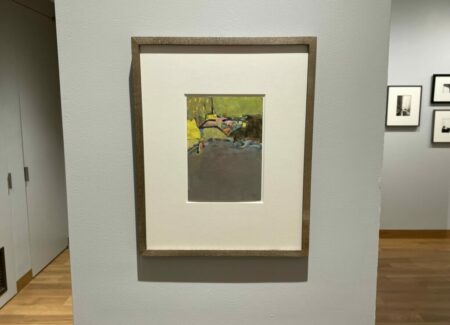

Many of these quiet nudes then became the starting point for another round of artistic exploration, via expressive overpainting in watercolor and gouache. Like his dappled wet windows, the paint has the effect of softening the crispness of the photographic eye, allowing for a sensuous blurring of color and obscuring of specificity. Most of the forms have been reduced to gestural movements and approximations, while a few have traversed all the way to complete abstraction, with compositions that feel like they might be based on something representational, but have been intentionally pushed toward shimmering effects and more elemental color arrangements. By hanging the photographs and paintings together, the show highlights the continuum of aesthetic thinking going on, and the connections and evolutions taking place between one expressive mode and another.

In a certain way, this show is an eclectic relative of a more definitive Leiter retrospective, following the same overall structure but filling in the specifics differently with available works. Most importantly, it successfully guides us through the chapters of Leiter’s artistic life, teaching us the key lessons from his career, but with alternate examples. Perhaps the best way to think of this show is as a worthy companion to the thick retrospective monograph recently published, adding in richness to a story told more robustly elsewhere.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show range in price from $5000 to $40000. Leiter’s work has begun to enter the secondary markets more consistently in the past few years, with recent prices ranging between roughly $2000 and $25000.