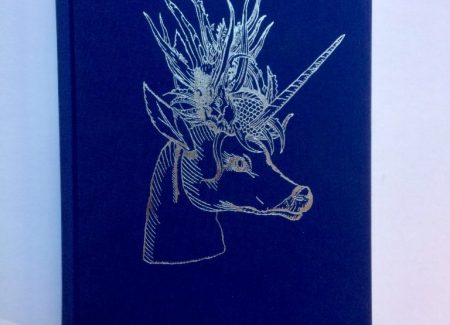

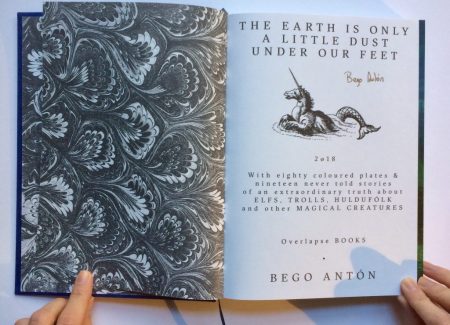

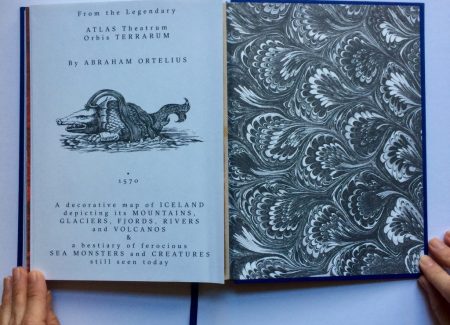

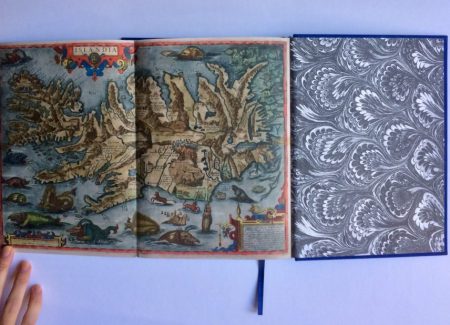

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2018 by Overlapse (here). Trade hardcover with silver foil on linen wrapping on front, back, and spine; section-sewn binding with bookmark ribbon; silver and ‘glow-in-the-dark’ special inks. 216 pages, with ninety-three color and black-and-white photographs, as well as three illustrations, 6.69 x 9 inches. Includes nineteen texts by Bego Antón and Santi García, six text fragments, as well as an endpaper fold-out of a decorative map. Designed by Nicolas Polli, edited by Bego Antón and Nicolas Polli, proofread by Tiffany Jones. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: In 1893, W.B. Yeats published The Celtic Twilight. “This handful of dreams”, as Yeats referred to his chronicle of Irish folklore, consists of stories the poet collected from friends, neighbors, and acquaintances, to which he added his own visionary, experiences. Amongst the book’s first chapters is “A Teller of Tales”, a brief homage to one Paddy Flynn, “a little bright-eyed old man”, who was, as the title states, a gifted “teller of tales”. “And unlike our common romancers,” Yeats writes, he “knew how to empty heaven, hell, and purgatory, faeryland and earth, to people his stories“. What Yeats so emphatically embraces in this short sentence, can also be described as the conflation of fact and fantasy. Advocating the blurry boundaries between the known and unknown, his dedication to “ancient simplicity” and “amplitude of imagination”, common not only in Irish, but all folklore, storytelling; as well as a poet’s commitment to truthfully and respectfully transcribe oral narratives, are among the reasons why the final lines of “A Teller of Tales“ also resonated with Spanish photographer Bego Antón:

“Let us go forth, the tellers of tales, and seize whatever prey the heart long for, and have no fear. Everything exists, everything is true, and the earth is only a little dust under our feet.”

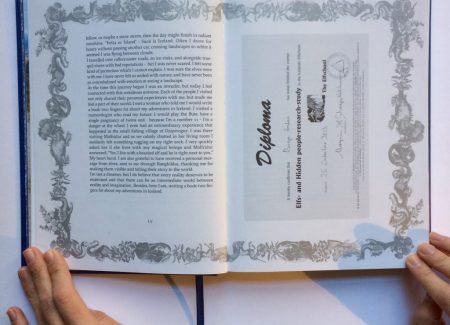

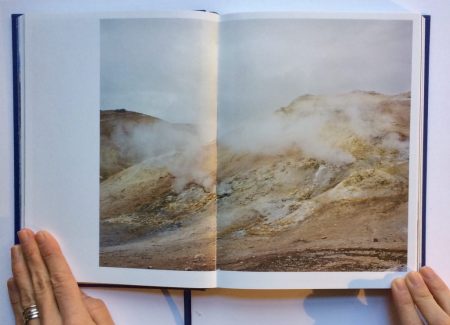

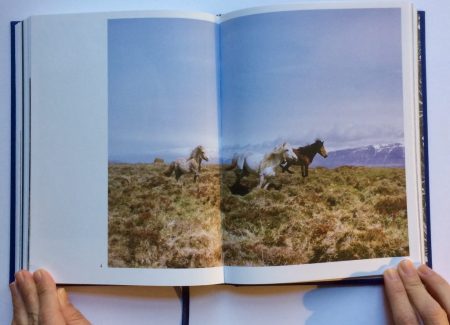

Grounded in the premise that closeness to nature may likely incite belief in – and experience of – magic, Antón’s The Earth Is Only a Little Dust Under Our Feet is a direct reference to Yeats’s text. Her book, however, introducing “eighty colored plates & nineteen never told stories of an extraordinary truth about elfs, trolls, huldufólk, and other magical creatures” (as the title page states), came about from her 2013 residency in Ólafsfjörður – a small town in northern Iceland. When looking for a new project, Antón discovered the website of The Elf School in Reykjavik. Intrigued, she attended the daylong seminar and received a diploma in “Elfs-and Hidden people-research-study”. What began as a curiosity, resulted in a five-year-long project, during which Antón travelled “from north to south and from east to west of the island, searching for places where the magical beings live.” Yet she was even more interested in finding the people with “the ability to see them”. And she did.

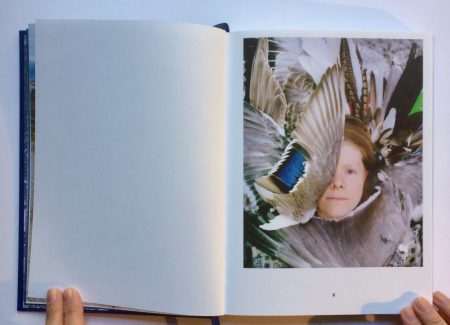

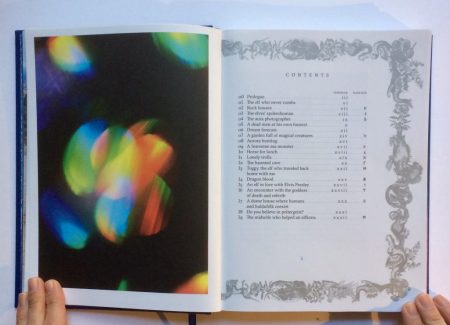

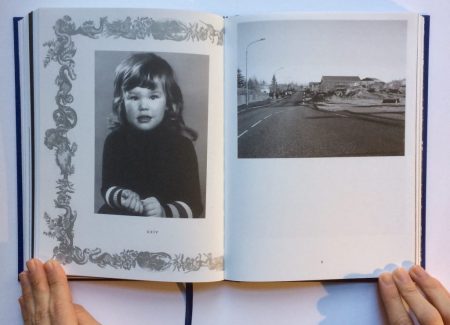

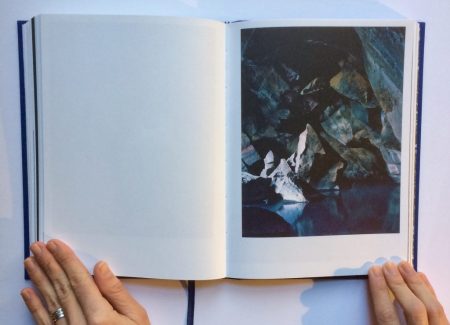

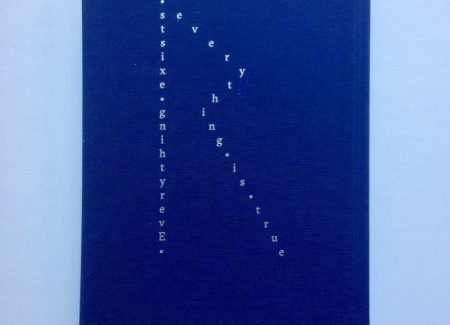

An homage to storytelling in its own right, The Earth Is Only a Little Dust Under Our Feet takes the shape of a Victorian-era book of fairy tales or fables – and exudes the kind of marvel that only childhood or longing can impart to an object. Graceful like a well-fit glove, a blue fabric tightly wraps the cover. Absorbing any source of light, the color is rich and infinite, as if shushing the eyes for the silvery outlines in its center. Bold and sentimental like a tattoo on some ancient sailor’s arm, a shimmering unicorn encourages you to turn the pages. As you reach the table of contents, you’ve crossed paths with close-ups of rainbow-colored rock- and ice-formations, magnificent landscapes, and the headshot of a woman, who, given the intricate feathers surrounding (and partly covering) her face, can’t be anything but a shaman.

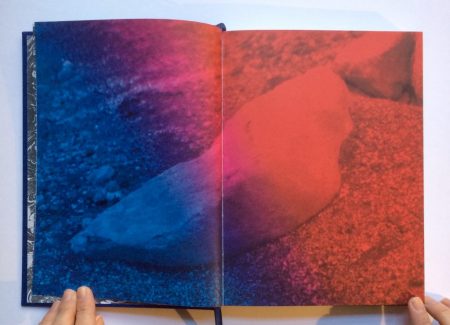

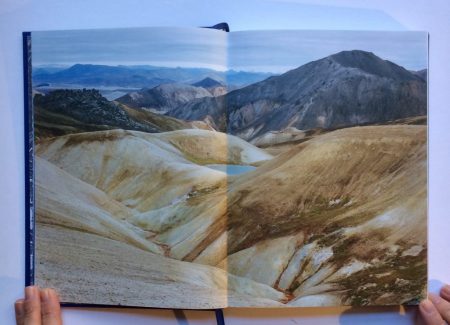

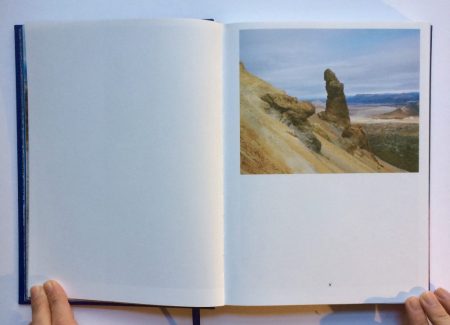

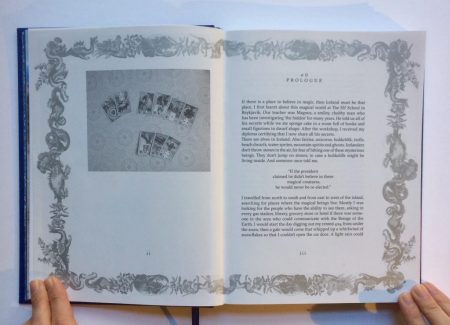

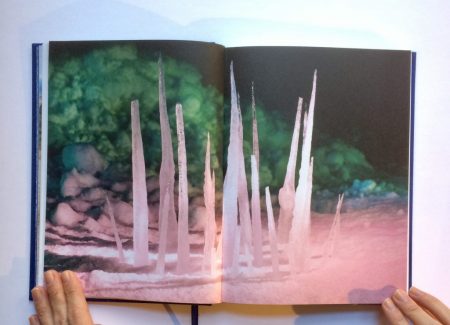

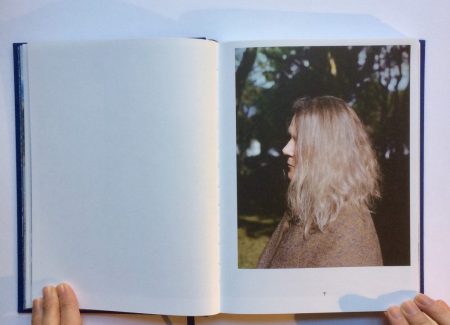

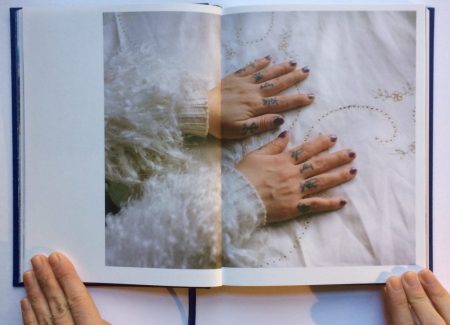

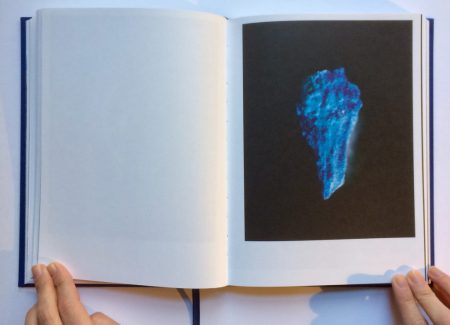

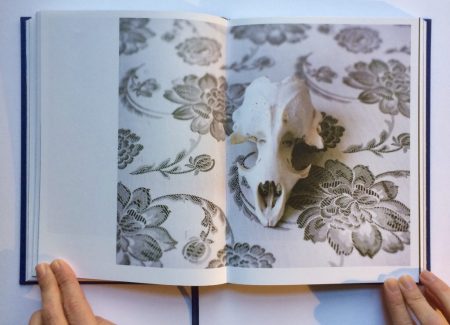

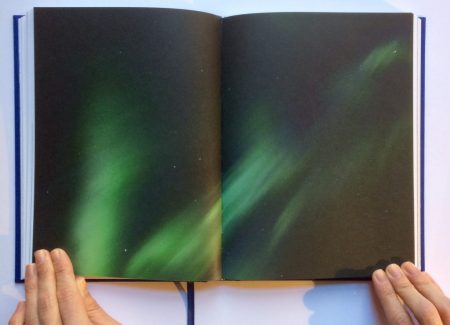

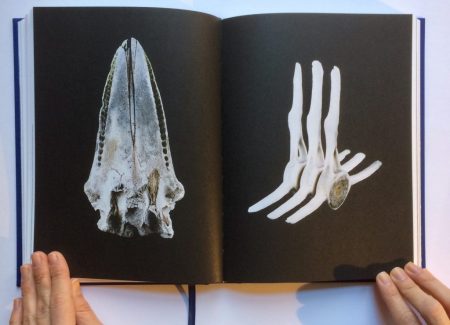

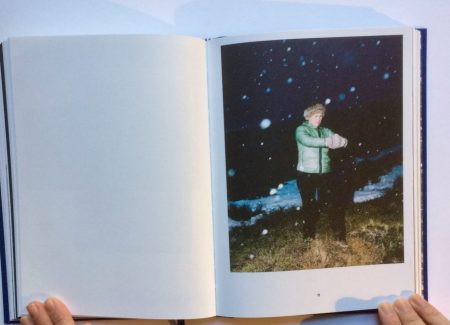

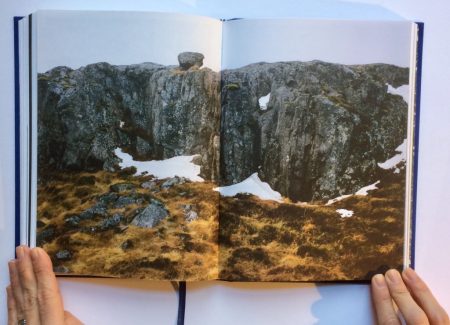

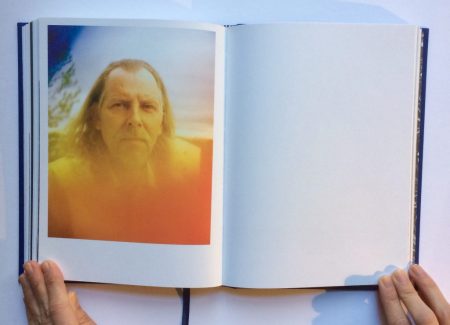

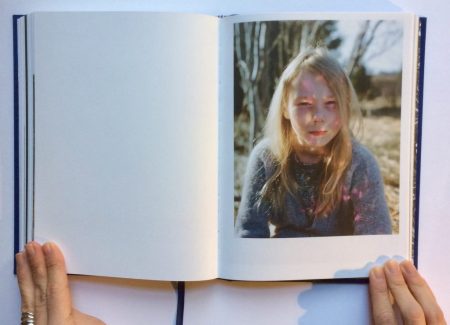

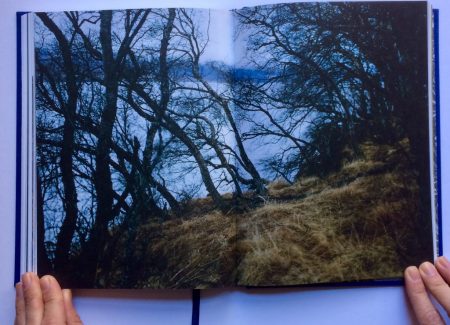

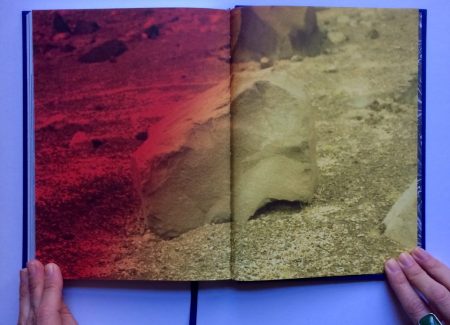

While Antón’s “Prologue” provides you with insightful descriptions and background information of her journey and motivation, including a reproduction of her diploma, it’s her color photographs that make up the main body of The Earth Is Only a Little Dust Under Our Feet. Soft in gradation and lush tonality, they range in size from a small notebook, to full-bleed single- and double-spreads. Printed on thick paper, many of her images show the deserted, mountainous landscapes, populated by patches of grass and moss, altering layers of ice, and forests. Other photographs zoom-in on detail, such as individual boulders, stones, and trees, as well as animal bones, the night sky, and the colorful streaks of the aurora borealis. The best of Antón’s images, however, are those of people, inside their homes or out, connected to a place, element, or animal of their choice. With attention to detail such as a certain gaze, the movement of a hand, worn nail-polish, or the pattern of a fabric, they are portraits, intending to characterize the respective person they depict – whether the sitter engages or neglects the camera.

You might, of course, wonder about the elves and the magical creatures. But like Antón herself, you won’t be able to see them – at least, not explicitly, but only through the eyes of others. In conversations preceding her photographs, some of the Antón’s subjects told her that they were sensitive to auras and energies, which, depending on the temperament of the respective being, appeared to be blue, green, yellow, or red. In order to make their experiences palpable, the photographer represents these effects through the use of filters, colored plastics, sheets, and prisms.

Antón came to photography through journalism, but she quickly realized that it wasn’t for her. “My way of organizing and playing with ideas is different. Instead of describing them, I want to tell them. In images,” she told me. And while she is “not a dreamer”, she does “believe that every reality deserves to be examined and that there can be an intermediate world between reality and imagination”.

The Earth Is Only a Little Dust Under Our Feet isn’t Antón’s first project engaging the contradictory, at times mysterious, relationship existing between humans and the natural world, or subjects on the margins of society. Her previous works include Everybody likes to Cha Cha Cha – a series about “Musical Canine Freestyle” (yes, dog owners dancing with their dogs) – or Butterfly Days, for which she documented a small group of people living in Southern England and their passionate, perhaps metaphysical, interest in butterflies and moths.

However, for The Earth Is Only a Little Dust Under Our Feet, she knew that images weren’t enough to thoroughly capture and engage “the concepts of real and phantasy”, which is why she knew from the beginning that she wanted to make a book. “Because it allows me to tell stories differently.”

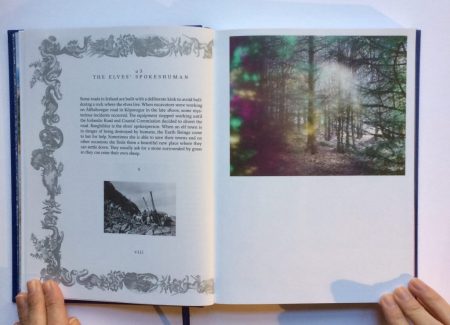

With images, like the one of a teenage-girl, facing the camera with such determination and defiance, that any doubts in her beliefs seem futile – the photographs of The Earth Is Only a Little Dust Under Our Feet are self-contained works that run deep and can stand on their own. Yet, they truly begin to shine once you connect them to the stories throughout the book. There is, for instance, the story of Ranghildur, the Earth Being’s self-declared spokesperson, who contacts the Icelandic Road and Coastal Commission to request the deviation of a road if certain formation of rocks – the habitat of magical beings – is under threat. Or the story of the aura photographer Brynjoldur, the only person on the island to own a scanner that captures a moving image of an energy field, which allows him to (successfully) spot diseases. Then there is Antón’s visit to a home for the elderly, where a group of residents successfully forecasts the weather based on their dreams, or the story of a dead man attending his own funeral. Written with candor and meticulousness, all of these tales vary in tone, but not in their intention to distill and testify to a truth that mere logic will never grasp.

At first glance, you might think that text pages make for another book within The Earth Is Only a Little Dust Under Our Feet. And to some extent they do: Printed on thinner paper, and enriched with silver ornaments and tiny black-and-white photographs – some of which were taken by Antón herself, while others were appropriated or given to her – they seem of a more inductive, or archival nature, than the color photographs. But, in fact, almost every story directly relates to an image – both of which are connected by an index of symbols from the rune alphabet (which are printed on the respective text and picture pages alike).

The photographer as storyteller is trope that emerged as soon as people began to pair images with text, creating narratives. The exploration of the supernatural occupies a specific place within this tradition. Whether it is the spirit photography of the nineteenth century, collected in albums and enhanced by enigmatic descriptions of séances or the appearing ghost; or more contemporary variations, such as Laia Abril’s Lobismuller, a brilliantly creepy reconstruction of the life of a 19th century serial killer, who considered himself a werewolf, and was purportedly living with the syndrome of intersexuality; or Virginie Rebetez’s Malleus Maleficarum, an investigation of mediums and healers grounded in the story of Claude Bergier, who was accused of witchcraft, and burned in 17th century France.

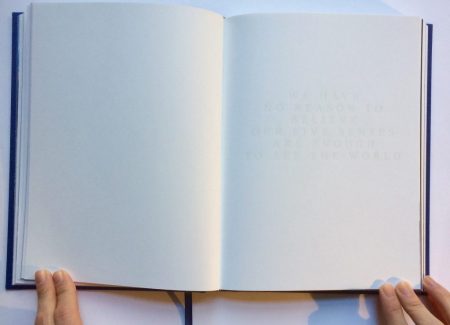

Yet, as much as The Earth Is Only a Little Dust Under Our Feet might be considered a book of stories and images, ghostly photographs, and outrageous tales – the magic Antón encounters and evokes, is never evil, or frightening, but instead a means of reciprocity. As all fairy tales and fables, also The Earth Is Only a Little Dust Under Our Feet aims to bridge the past with the present, continuing and preserving oral traditions and archaic beliefs. As such it also contains a space for one’s own imagination, even skepticism, materializing in a deliberate number of white pages that are interspersed throughout the book. If you look closely, some reveal secret messages such as “When you turn the radio on, so you see waves?”, “We call magic to things we can’t understand”, or “You can only see what you understand”. And even if you decide to remain a skeptic, you might be able to treasure The Earth Is Only a Little Dust Under Our Feet’s carefully considered design, its preciousness as an object – perhaps most beautifully rendered in the reproduction of a 16th century a fold-out map at the book’s end. It shows Iceland surrounded by sea monsters and all sorts of magical creatures – a reminder that the belief in magic is ingrained in the country’s history and mythology.

Given our continual estrangement from – and willful destruction of – the wilderness that surrounds us (throughout the past fifteen years Iceland’s number of tourists has quadrupled) – Antón’s book pursues a courageous and empathetic mission: not only does it value a culture rich in imagination, it is also a humble reminder of respect and indulgence. Most importantly, though, it allows for a special kind of encounter – with an ability that most of us used to have, but have lost along the way. Enchantment.

In a passage of Marco Polo’s Book of the Marvels of the World, the travelogue he composed after his return from China, Polo describes the animals he encountered. One passage is dedicated to the unicorn:

“They have hair like that of a buffalo, feet like those of an elephant, and a horn in the middle of the forehead, which is black and very thick. They do no mischief, however, with the horn, but with the tongue alone; for this is covered all over with long and strong prickles. […] The head resembles that of a wild boar, and they carry it ever bent towards the ground. They delight much to abide in mire and mud. ’Tis a passing ugly beast to look upon, and is not in the least like that which our stories tell of as being caught in the lap of a virgin; in fact, ’tis altogether different from what we fancied.“

The animal that Polo and his contemporaries commonly described as a unicorn, is known today as the rhinoceros. As Yeats, who reappears the silvery letters on the back of Antón’s book, has said: “Everything exists. Everything is true.” Only time will tell.

Collector’s POV: Bego Antón doesn’t appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. Collectors interested in following up should contact the photographer directly via her website (linked in the sidebar).