JTF (just the facts): A total of 15 color photographs, framed in white and unmatted, and hung against white walls in the main gallery space and the reception area. All of the works are archival pigment prints, made in 2008, 2009, and 2010. The prints are available in three sizes – 17×17, 29×29, and 37×37 inches – and are available in total editions of 7+2AP (regardless of print size). (Installation shots below.)

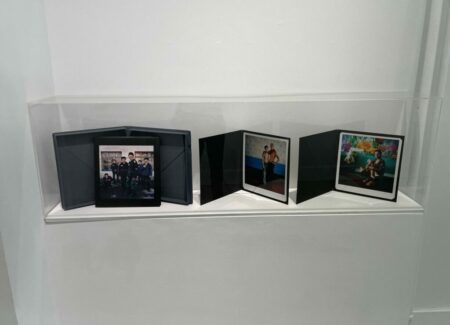

The show also includes a vitrine with a clamshell edition of the photobook Sailboats and Swans, with chromogenic prints, made in 2010 and printed in 2012. These prints are sized 10×10 inches, in editions of 30+12AP. A copy of the original 2012 edition published by Twin Palms (here) is also on view. (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, our news feeds and newspapers have been filled with a steady stream of images of people on both sides of the conflict. Politicians, soldiers, and everyday civilians caught in the crossfire are the principals in many of these photographs, and as the months of brutal war have dragged on, the kinds of pictures that we are regularly being exposed to have become almost routinized, with noticeable patterns in the ways the hubris of aggressors, the tenacity of defenders, the destruction of cities, and the plight of local victims are portrayed.

Michal Chelbin started making portraits of Russian and Ukrainian prison inmates in 2008, several years before the first invasion of Ukraine by Russia in 2014, and unlike the photojournalistic images of war we are now consuming, her photographs don’t offer any easy answers or neatly polarized characterizations. In fact, the staging of a show of this older body of work, titled Sailboats and Swans, at this particular moment in time of conflict intentionally forces us to wrestle with a range of expectations and preconceived notions, particularly in terms of what we assume a criminal or a prison in one of these countries is supposed to look like.

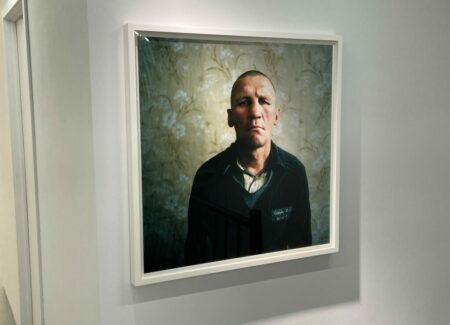

Chelbin worked on the project for a total of six years, visiting seven different prisons in the two countries, balancing her attention between men’s and women’s facilities, including those specialized for juvenile boys or girls. Each portrait session was voluntary, and Chelbin was careful never to know the crimes or the sentences of her sitters until after she had made her photographs, so there are no hidden clues or inherent biases to help us distinguish a small time thief from a violent murderer, or a two year sentence from a lifetime charge. What is perhaps most ironic, given the horrific grimness of many prison facilities, are the many floral wallpapers and painted mural backgrounds that she discovered and used in her portraits; the softness of the imagery directly contradicts the hardness of our (likely correct) perception of prison life, immediately putting us off balance.

Already wrong-footed by the settings, we now return to the even deeper mysteries of what a criminal really looks like. Each portrait is an attentive confrontation, where the sitter is both seeing and being seen – eyes invariably look right at the lens, creating a tight link between viewer and viewed. What emerges most consistently from these photographs is the reality that these prisoners are not anonymous; they are individuals, with stories to tell, and their participation in Chelbin’s project is a signal that they don’t want to be forgotten or overlooked, even if they are locked away.

Broken noses, gouged eyes, and hollow stares populate many of the images of men and boys, hinting at some of the traumas that are taking place off camera. Chelbin’s portraits combine an unsettling mix of hard and soft, where toughness and vulnerability are two competing sides of nearly every sitter. The floral backdrops further amplify this subtle sense of dissonance, as do many momentarily slumped poses, where a sitter’s guard comes down for just an instant – Stas leans back on his bunk, tattooed Vania is still within the shadows, and a group of boys huddles outside with the protection of numbers providing some safety. In other portraits, the darkness of the stares is more relentless, from Skarhod’s grim frown to Sergey’s vacant blankness, making the painted scenes and flowery patterns that surround them all the more surreal.

Chelbin’s images of female prisoners, both women and girls, have a different mood, almost more protective, as though staged in a convent or hospital. Nadia quietly crafts artificial flowers in the pure light of the morning, while Diana and Lila care for their infants surrounded by flower decals and stuffed animals. In other images, the girls sit on sparse beds or stand outside among the birch trees, almost like they are at summer camp. But vacant stares, controlled looks, and the evidence of injuries soon reappear in some of the portraits of somewhat older women, who have developed more coping mechanisms for dealing with the realities of prison life. Nearly all of these portraits feel calmly resigned, as if the more vibrant personalities of the women have been muted, or at least hidden away for awhile.

As with neatly all formal studio portraiture, the real magic happens when the sitter actually reveals him or herself; since the invention of the medium, photographers have tried countless ways to get subjects to show their true personalities, and the prison context here both helps and hinders that effort. On one hand, there is a desperation for being seen that lies underneath some of these pictures that likely fostered some of the willingness to engage that we witness, but the invisible protections that the inmates have put up around themselves are even more hardened and practiced than usual, so Chelbin’s portraits end up documenting a mix of these realities. Most commonly, Chelbin’s compassionate eye captures a look of deadened shock, which no amount of incongruously soft floral wrapping can undo. In the end, it is the silent personal isolation that pervades these pictures that is so dispiritingly wearying, seemingly grinding each individual down in his or her own way, day by day by day.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced at $4000, $5500, or $7500, based on size. Chelbin’s work has little secondary market history, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.