JTF (just the facts): A total of 30 black and white photographs, framed in white and matted, and hung against white walls in the single room gallery space. All of the works are vintage gelatin silver prints, made in 1968. All of the square format images have been printed on 11×14 inch paper, and no edition information was provided. (Installation shots below.)

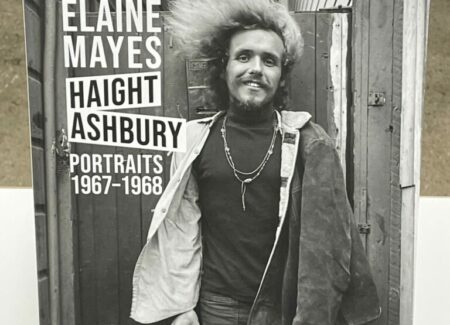

A monograph of this body of work was published in 2022 by Damiani Editore (here). Hardcover, 96 pages, with 50 black-and-white reproductions. Includes an essay by Kevin Moore. (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: When photographers decide to make portraits on the streets and sidewalks of a busy urban environment, almost the first question they have to wrestle with is how to engage their subjects. Will they stay a few anonymous steps back, in essence snatching portraits from relatively unsuspecting passersby, or will they stop and engage their potential subjects, creating a momentary personal connection that will enable a different kind of portrait-making? This seemingly obvious decision turns out to be a crucial one, as the kinds of pictures that emerge from the two approaches tend to be markedly different in tone and feel.

In the summer of 1968, Elaine Mayes was living in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco, and had come to the conclusion that the media’s broad portrayal of the 1967 Summer of Love, and in particular the young people who were living in the Haight at that time, had left out important nuances. The simple through line of optimistic hippies, music, psychedelic drugs, the anti-war movement, and free love connected some of the dots, but a year later, the mood was shifting ever so slightly, with the tougher realities of living on the streets becoming more apparent. Mayes had made photographs of concert goers at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 in a photojournalistic style, but she decided for her portraits of the young people in the Haight to move back to a more formal approach, with her square-format Hasselblad perched on a tripod and each picture requiring the authentic engaged collaboration of a longer exposure.

The photographs that emerged from this process weren’t an arms-length anthropological study; Mayes had moved in closer, actively interacting with young people (nearly all in their late teens or early 20s) she met on the street in her neighborhood. Most of the images seem to have been made wherever she encountered her sitters – on the sidewalk against a nearby wall, sitting on a stoop or in a doorway, or against a tree in the park, with a few inside seemingly where the person lived. What’s surprising about the pictures is just how consistently direct they are – every single person (or group) looks directly into the camera with a kind of quiet intensity, actively participating rather than passively being seen.

In making these portraits, Mayes was deliberately cutting across the hippie stereotypes of the day, looking closely and compassionately at individuals and their choices rather than at broad brush assumptions or criticisms. Her pictures run the gamut from single individuals to groups of half a dozen young people, with friends, couples, families, and young mothers with their infants or toddlers all fitting comfortably into the community around her; she similarly captures a range of young men and women, white and Black, without particular emphasis on any one race or gender. In each and every photograph, we get a connection with a complicated person, not a confirmation of a type, even when the stylistic signifiers of the age (long hair, scraggly beards, bare feet, peace medallions, guitars, and traveling backpacks) are prominently present.

Mayes’s portraits are generally sparse and intimately framed, but even with just a minimum of surroundings, she often finds a resonant detail that gives us a clue to a story or at least something that gives her sitter a sense of individuality. She notices a huge American flag as a wall hanging, plenty of bibles and crosses (and one stained glass Jesus), a motorcycle, a pair of slippers, a checkered suit, a cat, a number of earnestly held thick books, a scrawl of Where Has All the Love Gone? on a nearby wall, a torn curtain, and a hand-drawn double bill of “How I Won the War” and “Black Orpheus”, each detail filling out potential situations and personalities. Her titles also offer a few more signposts, from “Kathleen, Pregnant at 16” and “Man Who is Avoiding the Draft” to “Two Women from Atlanta” and “Sherry Johnson Wearing Tablecloth”. Seen as a group, her results are understated but engrossingly open-eyed and attentive, with optimistic hope and disillusionment both lingering in the shadows.

In the time capsule of that period, Mayes’s photographs fit between Jim Marshall’s images from the Haight from a few years earlier (his with a more music, crowds, and atmospheric focus) and Richard Misrach’s street portraits from Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley from the early 1970s (which use the same formal tripod approach that Mayes used). The gap she fills is an important one, both historically and stylistically, and these portraits deserve to be better known than they are. Mayes gets the contract of trust-driven photographic portraiture just right, leading to intimately seen and often revealing single frame stories of actual people, not categories. Her pictures from the Haight are indeed a step back into the past, but they remain filled with a freshness and energy that hasn’t been diluted by the passing of time.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced at $8000 each. Mayes’s work has little secondary market history, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.