JTF (just the facts): A retrospective exhibition, spread across four divided rooms on the main floor of the museum. The show was organized by Drew Sawyer.

The following works are included in the exhibition:

Part I: 1968-1976

- 1 set of 2 gelatin silver prints, 1969

- 1 set of 3 gelatin silver prints, 1972/1974

- 4 dye diffusion transfer diptychs, 1974

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1977

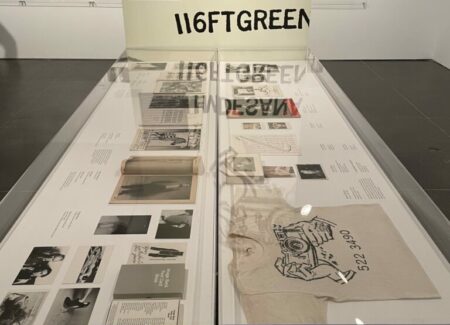

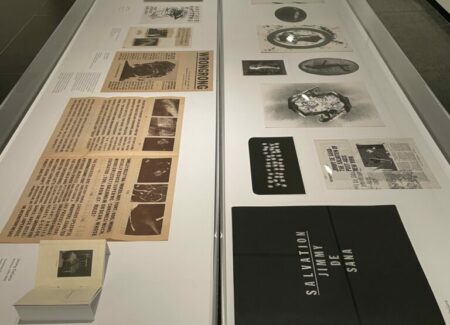

- (4 vitrines): t-shirt 1973, magazines, newspapers, Polaroids, collages, image bank postcards 1977, mailings

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1973

- 3 gelatin silver prints, 1973, 1975

- 2 gelatin silver prints, 1975

- 3 gelatin silver prints, 1973, 1976, 1977

- 2 chromogenic prints, 1980, 1981

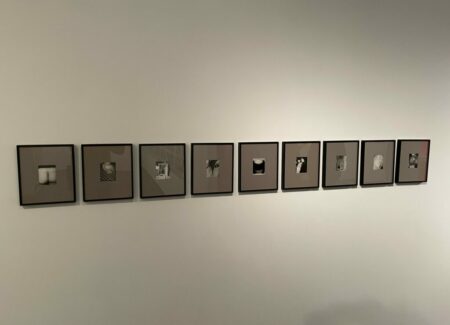

- 1 set of 9 gelatin silver prints, 1977

- 1 portfolio 101 offset prints, 1972

Part II: 1976-1984

- 10 gelatin silver prints, 1978 (with Terence Sellers)

- 1 video (Sylvere Lotringer interview with Terence Sellers), color, sound, 1982, 14 minutes 1 second

- 1 video (Coleen Fitzgibbon, Alan W Moore), b/w, sound, 1978, 11 minutes 40 seconds

- 3 gelatin silver prints, 1978

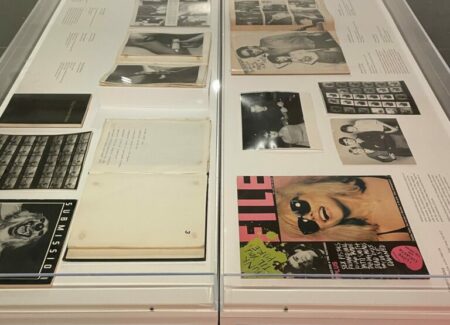

- (2 vitrines): magazines, contact sheets, album covers, artist’s books/maquettes

- 4 chromogenic prints, 1977, 1981, n.d.

- 8 gelatin silver prints, 1977, 1978

- (in red light room): 24 gelatin silver prints, 1977-1978

- 3 gelatin silver prints, 1977-1978

- 1 chromogenic print, 1978

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1979

- (vitrine): newspapers, magazines, photocopies, opening cards, books, contact sheets

- 1 16mm film, color, 1979, 10 minutes 45 seconds

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1979

- 1 Super8 film (Michael McClard), color, sound, 1979, excerpt 22 minutes 25 seconds

- 4 silver dye bleach prints, 1979, 1984, 1985

- 1 cibachrome print, 1979

- 14 chromogenic prints, 1979, 1980, 1980-1982, 1981, 1982

- 2 inkjet prints, 1980/2022, 1981/2013

- 1 video (Matt Wolf), color, sound, 2017, 3 minutes 23 seconds

Part III: 1984-1990

- 11 silver dye bleach prints, 1981, 1984, 1985

- 5 silver dye bleach prints, 1986/1987

- 1 silver dye bleach print, 1986

- 4 silver dye bleach prints, 1985

- 3 silver dye bleach prints, 1985, 1986

- 1 set of 7 silver dye bleach prints, 1987

- 1 set of 3 dye bleach prints, 1987

- 5 silver dye bleach prints, 1987

- (vitrine): magazines, photocopies, photobook maquette, opening cards, newspapers

- 2 silver dye bleach prints, 1988

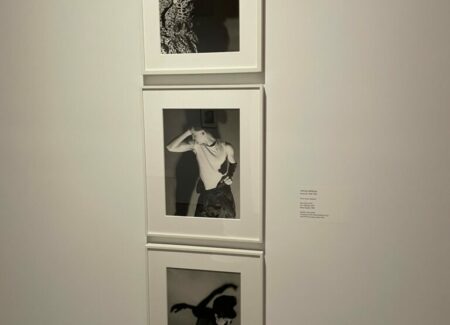

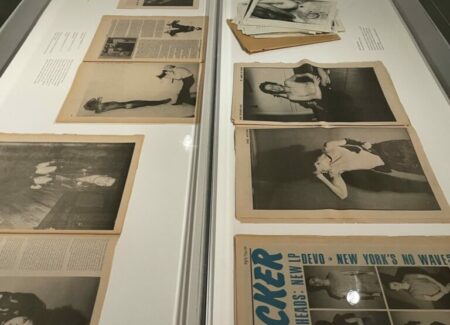

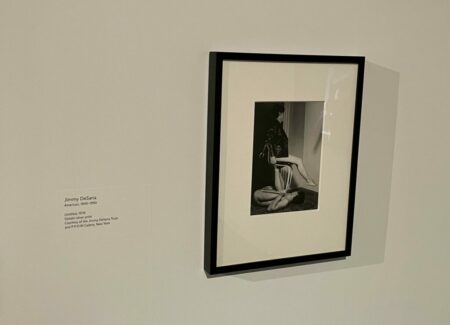

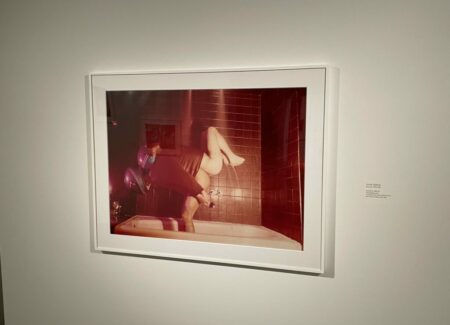

(Installation shots below.)

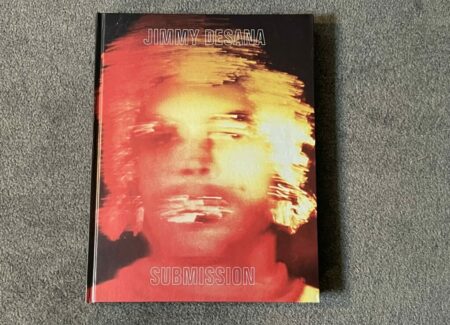

A catalog of the exhibition has been co-published by the museum (here) and DelMonico Books (here). Hardcover, 176 pages. Includes essays by Drew Sawyer and an epilogue by Laurie Simmons. (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: Given the significant amount of time and effort that is invested in the creation of career-spanning retrospective exhibitions, it’s not entirely surprising that the eventual scheduling of such exhibits often feels strangely timed. In many cases, a retrospective arrives long after an artist’s reputation has been cemented, so the exhibition can feel almost too safe and crowd-pleasingly obvious, like we already know much of what is being presented, making the whole enterprise feel like a victory lap. In a sense, when our reaction is “Now?”, we can assume that the art world collectively missed its chance to educate us and shape our opinion about the artist much earlier, and so the retrospective comes “too late” to matter all that much, except as a congratulatory and confirmation milestone.

In other cases, artists that would meaningfully benefit from a retrospective never quite get one, so our questions simmer and pile up answered. Often exactly what such an artist (and the audience) needs is the clarifying through line that an insightful curator can pull though a messy career of art making. And so when our reaction to the announcement of a retrospective is instead “Finally!”, we know that it is both overdue in some larger and more amorphous chronological sense of art historical importance, but still urgent and relevant, in that we’re keen to see the artist’s story told much more fully.

In the roughly three decades since he died, and particularly in the past decade or so, Jimmy DeSana’s work has been bouncing around in the New York art and photography worlds with surprising consistency and potency, but without much coherent context. His images have shown up in solo and group shows, as adjacent to (or part of) the Pictures Generation, as an essential element of queer art and AIDS-related art making, in process-centric photographic discussions, in vitrines of 1970s mail art, in posters and album covers from New York’s underground music subcultures, and as documentation of S-M practices. How all that creativity actually fits together was never quite explained, even with Laurie Simmons and other still-living artists of his generation championing his cause. So my own reaction to seeing this DeSana retrospective pop up on the calendar was absolutely “Finally!”, with the hopes that the arc of his narrative, and his durable importance as an artist, would get clearer.

Thankfully, this exhibit is built atop a straightforward chronological scaffolding, with a distinct progression through early, middle, and late periods, which slots all of the aforementioned artistic interests and bodies of work (and several others) into a succinctly orderly survey, with key projects given deeper attention. The first room creates an initial framework for DeSana’s artistic perspective, offering a range of early works (some of them made while a student at Georgia State University) that find him testing out ideas and aesthetics. What’s fascinating is almost from the very beginning, DeSana was intrigued by the dissonance he saw between the stifling conformity of suburbia and his performative interest in the nude figure. His first works capture suburban houses at night and nude figures cavorting in bland domestic rooms, eventually taking shape in 1972 as a portfolio titled “101 Nudes” which pushed these ideas further, mixing conceptual staging with bluntly playful provocation. The black-and-white images from the portfolio feature both male and female figures posing nude in suburban settings – on furniture in the living room, on the dining room table, out in the garden, and in various other mundane settings (holding a dog, twisting the telephone cord, sitting at the piano) – the images blasted into eerie, high contrast strangeness by the use of overwhelming snapshot-style flash. Breasts, butts, genitals, and pubic hair are seen with a range of casual attention, blunt inspection, and fleeting glances, and the general prevalence of fully nude figures traipsing all around the house plays with our assumptions about the dull lives taking place behind closed suburban doors. DeSana introduces both theatrical absurdity and knowing deviance into this commonplace domestic setting, adding a dose of bite to dated definitions of “acceptable” private lives.

As seen here, the early and mid 1970s were a whirlwind period of artistic experimentation for DeSana, much of it taking place in alternative scenes or underground circles. He was exchanging irreverent queer mail art with Ray Johnson and others, contributing portraits to artist publications and magazines, and doing album covers for punk, No Wave, and New Wave bands, all the while refining his photographic techniques and aesthetics, particularly in his use of dramatic shadows, paparazzi-style intrusion, and performative color flares. Several vitrines are stuffed with DeSana’s ephemera from these days, each zine spread or collaborative image fragment documenting the simultaneously gritty, glamorous, and DIY downtown New York scene in which he was actively participating.

One of DeSana’s earliest self-portraits (from 1973) captures him nude, with an erection, hanging from a noose from an interior doorway, and in the years following, his interest in sado-masochism, fetishes, and bondage grew, as both a photographic observer and as a participant. One project (from 1978) found him collaborating with the author and dominatrix Terence Sellers on a series of images of Sellers with her clients, often in what she called the “Dungeon”; his photographs brought an artist’s eye to the proceedings, capturing the consistent tension between eroticism and violence and the performative aspects of the acts.

At about the same time, DeSana began his own series featuring many of the same ideas, that ultimately became the body of work “Submission”; prints from the project are shown in a side room lit with red light, further amplifying the atmosphere of knowing illicitness. And while the black-and-white photographs do feature figures posed in leather masks, panty hose, and high heels, with ropes, masking tape, dog collars, whips, dildos, and other S-M accoutrements, there is an edge of surreal wit and comedy in many of even the most dark and provocative of the scenes. Mundane suburban settings resurface in DeSana’s visual vocabulary, the shag carpets, dated sofas, and tiled bathrooms of bland homes becoming the stage for various transgressions, with scenes like a man awkwardly bent into a coffee table, another tied naked to the top of a family car, a third masturbating with the toothy smiling snarl of a dog nearby, and a woman folded inside a refrigerator filled with eggs enlivened by a splash of surreal playfulness. The strongest pictures from the series find a satisfyingly conflicted position, mixing real sexual desire and expression with smart undercurrents of parody and cultural criticism. When a submissive nude subject in a leather hood is forced to hold a TV up with his feet, it’s clear we’ve entered a hybrid world of visual consumption.

In the following years, DeSana continued to explore this intersection of S-M motifs and suburban life, now with the addition of more visual styles borrowed from fashion and commercial photography, including colored gels and tungsten lights that added more garish tints to the setups. In these “Suburban” pictures, DeSana skewers consumer culture with glee, turning a life of washing dishes, cleaning toilets, sitting on pool loungers, and eating hors d’oeuvres with party picks into a kind of sexualized bondage or torture. His allusions and scenarios are consistently clever, including the nude couple wrapped in plastic wrap posed with their fluffy white dog, the man asphyxiating himself with the exhaust from his car, and the man walking on green astroturf with orange cones on his extremities, and DeSana’s formal inventiveness shines in a pair of nudes connected by a plastic hangar, a body sliced into sections by cardboard sheets, and four kicking legs emerging from a gym bag. It was these “Suburban” photographs that pulled DeSana into the Pictures Generation orbit, and they remain some of his most engaging deconstructions of consumerism. Photography itself also gets upended, in an image of a female nude taking a photograph of a clothed man, the reversal of the seeing and watching (with the man actually hiding his face) made incisively surreal by a flare of pink light.

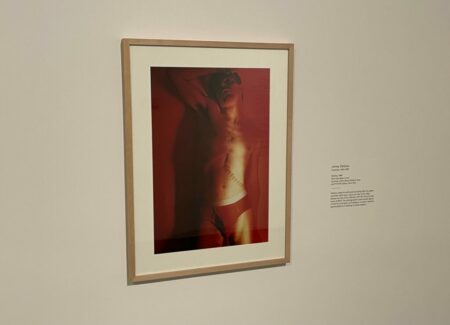

The logical progression of aesthetic ideas in DeSana’s retrospective loses steam a bit at this point, with a cross over through double doors into a final gallery that tries to sum up his work from the last half dozen years of his life. In 1984, DeSana’s spleen burst (apparently due to complications from celiac’s disease and HIV/AIDS), and the final section opens with a self portrait of the artist in deep red light, with a jagged stitched scar across his torso. It’s a haunting, anguished picture, and certainly makes clear that DeSana was increasingly aware of his own mortality.

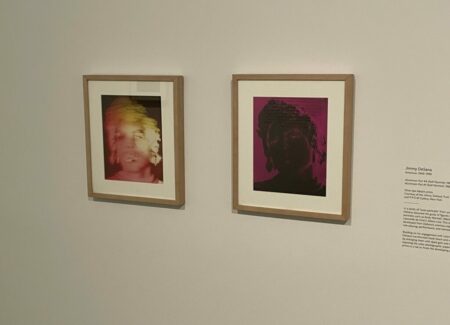

From there, DeSana seems to dive headlong into extending the boundaries of his photographic process, making the colored tints richer and more enveloping and exploring negative reversals, photogram techniques, and cutting negatives in peeled back starburst patterns. Some of the resulting pictures edge toward satirical surrealism (with bodies inflated and distorted, cellophane tape extending from a woman’s mouth like a tongue, and a doubled self-portrait in a crumpled tinfoil headcovering), while others leave the body behind and turn their attention toward simple still life objects, like a spoon, a softball, or a tangled ball of string, which DeSana bathes in deep color and transforms into something more poignant and reverential. The last few works introduce collage elements, mixing bodies and flowers in a triptych of X shaped forms and building portraits out of scavenged images of faces and objects, culminating in an unfinished maquette for a project titled “Salvation”. At the end of his life, DeSana was apparently interested in creating abstract works about “nothingness”, but the conceptual connective tissue that links the process-centric works in these last years (beyond an overtone of loss, death, and despair) is much less well defined and explained, and it feels like a deeper dive (with a few more works on view) might have made the key points of this late portion of DeSana’s career somewhat clearer.

DeSana’s durable legacy as an artist and photographer lies in the innovative ways that he grafted the charged sexuality and stylized aesthetics of queer subversive subcultures to the mundane realities of 1970s suburban America. It was a decidely daring and unconventional pairing, but in his hands, it turned out to be surprisingly resonant and approachable, particularly in the ways that it exposed natural veins of surreal eccentricity underneath a stifling surface of conformity. Hopefully, this handsome retrospective (and its accompanying catalog) will help reslot DeSana back into the right historical conversations, where his slyly sophisticated approach to disruption will be better appreciated.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum exhibition, there are of course no posted prices. Jimmy DeSana’s estate is represented by PPOW Gallery (here), which has a show of his “Dungeon Series” works on view between February 3 – March 11, 2023 (here). DeSana’s work has very little secondary market history, with only a handful of lots coming to market in the past decade or so. As such, gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.