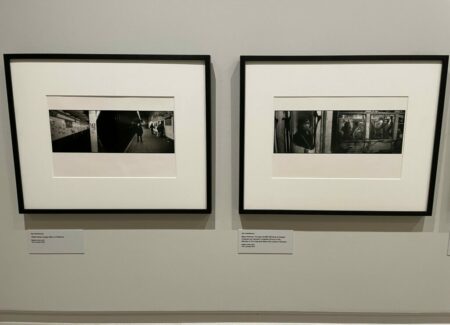

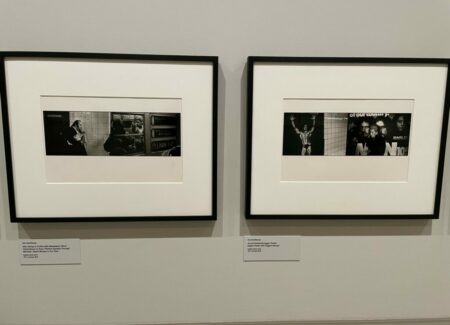

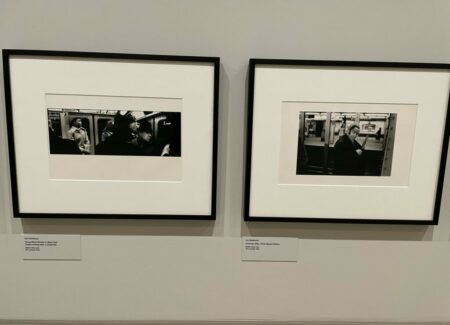

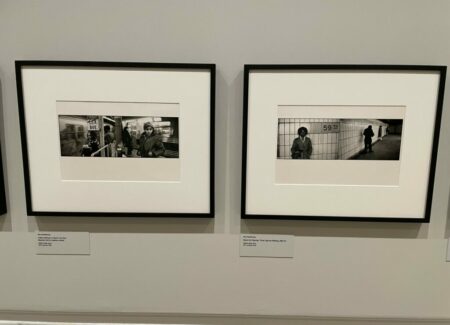

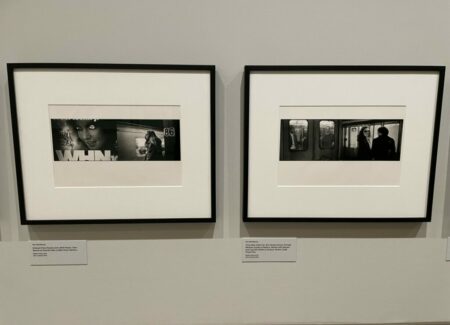

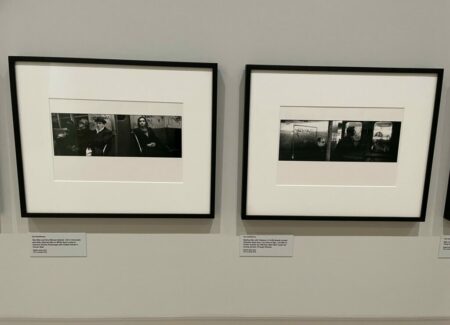

JTF (just the facts): A total of 44 black-and-white photographs, generally framed in black and matted, and hung against white walls on the third floor of the library. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- 42 gelatin silver prints (diptychs and singles), 1977/1979

- 2 large gelatin silver prints (diptychs), 1977/2005

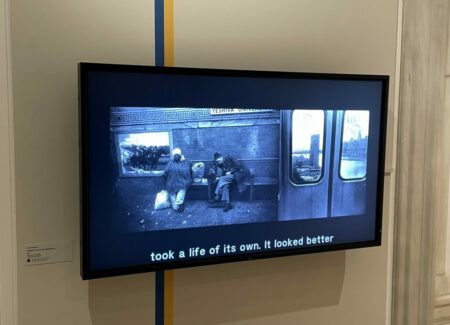

- 1 video, 2021, 12 minutes

- (vitrine): 1 photobook, 2022

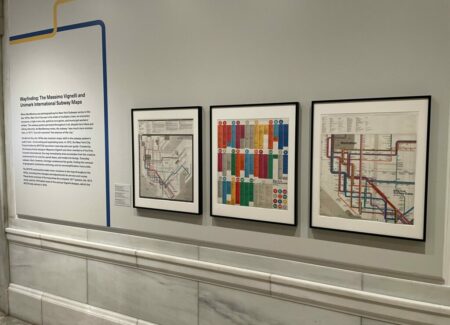

- 3 New York subway maps, designed by Massimo Vignelli, Joan Charysyn, Bob Noorda, Unimark International, 1972, 1974, 1977

Comments/Context: Even more than busy city streets, subways (and other mass transit systems) push strangers together in tight spaces, creating a steady stream of unlikely juxtaposition opportunities for ready photographers. The tight shoulder-to-shoulder seating, the democratic mixing of passengers, the crowded straphanger poses, the layered transparency of windows and doors, and the in-and-out movement and waiting taking place on the platforms all make subways an ever-changing source of inspiration, their popularity as a subject, not only in New York but around the world, making them the common location of their own special subgenre of street photography.

The list of photographers who have ventured down into the subways to make images is long and full of esteemed names. Walker Evans is often given top billing, with his hidden camera images of New York City subway riders from the late 1930s, but even a cursory glance through the history books will quickly bring up Stanley Kubrick, Helen Levitt, and Bruce Davidson, along with more contemporary efforts from Michael Wolf, Adam Magyar, Natan Dvir, and Reiner Gerritsen. Each artist has found his or her own way into the subway as a subject, from straight on portraits, down the car scenes, and fragmented overlapped bodies, to people pressed up against the glass, people reading books, and people arranged on the platform. And of course, New York isn’t the only notable venue, with Tokyo, London, Paris, and other locales each having their own subway photographers and projects.

Alen MacWeeney’s contributions to subway canon came in 1977, at a time when New York City was particularly grungy and the everyday life of subway system reflected much of that grittiness. Born in Dublin, MacWeeney was a press photographer and freelancer for fashion magazines before taking a job working as an assistant for Richard Avedon in New York. He rode the subway often during that time, from his apartment in the East Village to jobs uptown, and took along his camera, making images of the people and serendipitous New York moments he encountered along the way. And like any accomplished street photographer, he had an eye for the fleeting juxtapositions of riders that from time to time coalesced into a memorable single frame.

Back in his apartment, MacWeeney laid out dozens of prints in messy stacks and piles on tables, and it was something he noticed about this arrangement of his subway images that turned out to be an important flash of inspiration. What he saw was that when he put two of his images together as edge-to-edge diptychs, the seam in the middle would sometimes essentially disappear, making it look like the two pictures were actually one wide panorama. Soon MacWeeney was pulled into a deeper effort to make pairings, finding not only formal and structural patterns and resonances, but also the possibility for choreographed emotional connections, shared looks, and intimate interactions that hadn’t actually taken place but could be constructed by putting images next to one another.

MacWeeney is clever in his choices, and the frames aren’t always equally divided between the two images, making the illusionism harder to discover in a few cases. The most straightforward pairings create doubled sets of ideas: people in hats and bulky winter coats, people looking in the same direction, large faces on platform posters, repetitions of light reflections or silver metal handrails, and people sitting in corner seats or surrounded by graffiti. Other images play with the subtle linking of the two images, connecting sweeps of white tile, the platform posts used as architectural verticals, and blurred silver cars whizzing by, making two images with the same background characteristics almost appear like one.

The physical closeness of the subway creates plenty of alone together moments, and MacWeeney then builds on these separations to create new connections. One smart pairing places a young woman in a beret holding an overhead ring looking right with man in turtleneck and blazer looking left, the two together seeming to kindle a spark of romance, or the “missed connections” that used to appear in newspaper ads. Other pairings create the appearance of exchanged glances through windows, passing figures moving in different directions, and possible communications between those inside passing cars and those on the platform. Another resonant pairing combines looking out and looking in, with an old man in a Russian hat looking out, while we look in to a Black woman in a headscarf, with various glass distortions and light reflections further merging the two images.

Still other diptychs make unexpected matches, between an Indian woman and a Spanish girl, or two Black women in coats and a White woman in a coat holding a package. Subtle serendipitous comedy comes through in an image of a man holding a painting of a tiger connected to a picture of a graffiti covered car, with both images featuring dark crosshatched marks. And other single images or halves of pairings offer plenty of classic New York eccentricity, including Olivia Newton-John with her eyes scratched out, a woman with a doll, a man with a prominent “Christ is the Answer” button on his jacket, and a man with slicked back hair, long sideburns, and some seemingly illicit drumsticks. And then the train keeps moving, the cars rumble by, and we get a glorious momentary glimpse of the Brooklyn Bridge out the car window, regrounding us in the obvious reality that we are in the one and only New York City. And it is this second layer of re-interpretation that makes these works original and memorable. MacWeeney went beyond sustained observation and opted for something more abstract, where he actively played with (and reorganized) time, space, and intention. The strongest of his diptychs are a classic 1+1=3 situation, where two solid images come together to make something altogether more powerfully unexpected.

Collector’s POV: Alen MacWeeney does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. As a result, interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artist via his website (linked in the sidebar).