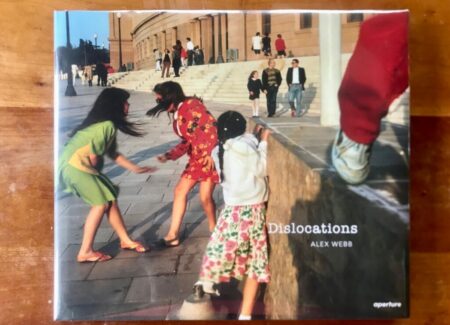

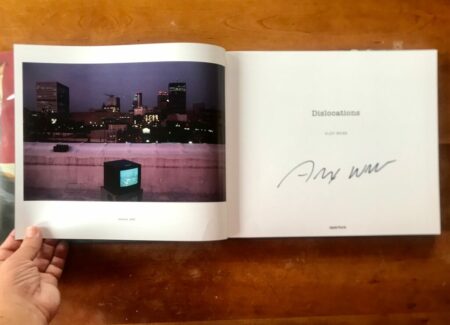

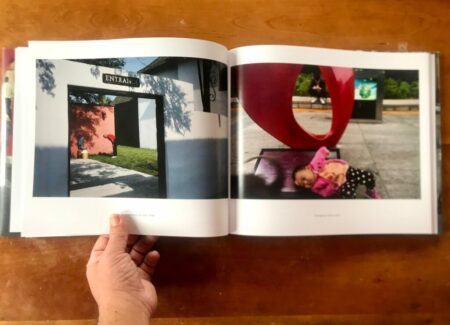

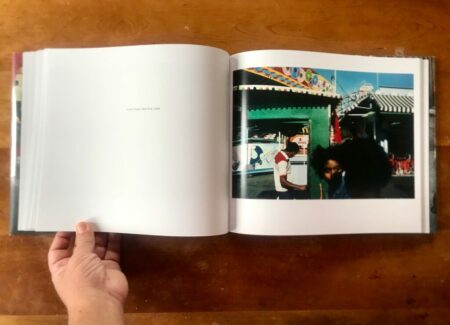

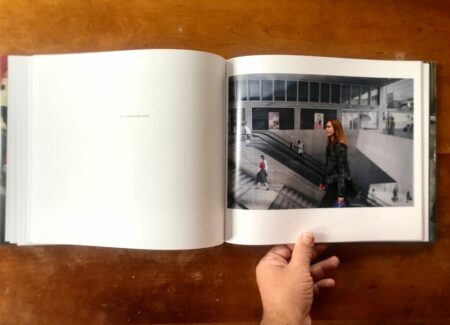

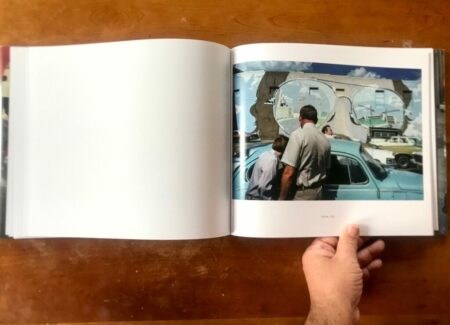

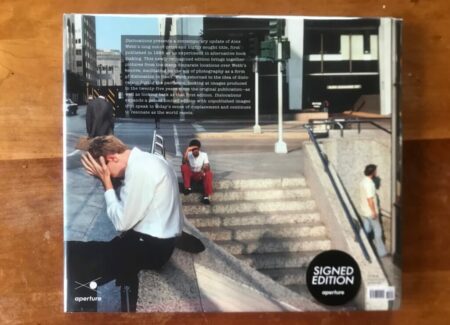

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2023 by Aperture (here). Hardcover with dust jacket, 11.8 x 10.2 inches, 128 pages, with 80 color photographs. Includes an essay by the artist. Design by David Chickey. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Alex Webb’s photography is rooted in candid observation. “I only know how to approach a place by walking,” he’s written, “for what does a street photographer do but walk and watch and wait and talk, and then watch and wait some more, trying to remain confident that the unexpected, the unknown, or the secret heart of the known awaits just around the corner.” When the stars align on occasion, the next step is to expose them with precision. Webb is a master at knitting visual scraps into tight compositions. He blends signs, gesture, pavement, weather, reflections, architecture, clothing, or whatever else is handy.

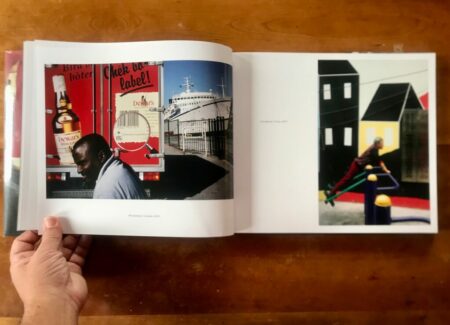

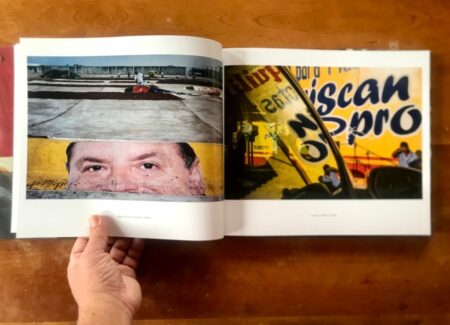

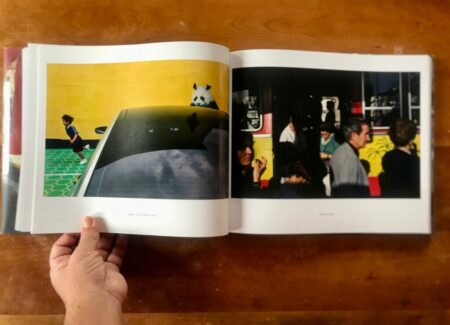

In his early career, these visual elements were captured in monochrome. In the late seventies Webb transitioned to color, and his sensitive treatment of tincture has developed into a signature trait. The bulk of his activity has been south of the border (e.g. La Calle, reviewed here) and thus his photos typically feature the bright colors and sharp lighting of afternoon tropics. Body parts alight from deep shadows, flatten into miniatures, or twist into statuesque poses. Murals and advertisements lend layers of trompe-l’œil ambiguity, while clouds and water provide visual spice.

Choreographing these unplanned elements into compositional jigsaws is a challenge. Not only has Webb mastered the technique, he’s probably its foremost living practitioner. Indeed he may bear some responsibility for its burgeoning popularity, although exact blame is hard to assign. Whatever the reasons, street photography in the 21st century has gravitated toward Webb’s style, notwithstanding the more character-driven approach of Daniel Arnold (reviewed here), Melissa O’Shaughnessy (reviewed here), and others. Browse contemporary street photography on Instagram and you’ll find reams of aspiring acolytes flouting a doom-scroll of juxtaposed limbs, shadow-play, frames-within-frames, and background posters. All are techniques from the Webb toolbox, but they require skilled application. In clumsier hands, they come off as cheap visual gags. Worse, an emphasis on formal rigor typically subordinates qualities like emotional depth, personality, and narrative context. Even integral traits like physical location become secondary.

These facts form the context for Webb’s latest book Dislocations. The book is a heavily revised edition of an earlier artist proof, published in a limited run in 1998. That version contained 58 photos, and the print run was 40. Aperture’s republication culls roughly two dozen photographs. Thirty-four have been held over, and dozens of new photos added. The whole collection–80 photos spanning 5 continents—has been resequenced and redesigned. All in all there are enough changes that the 2023 Dislocations stands on its own as a new title. That said, it contains vestiges of the first, including several well-loved Webb classics, and even the original silver title placard, now debossed under a new dust jacket.

That placard spells out the book’s raison d’être with a dictionary definition: Dislocation 1. Displacement; removal from its proper (or former) place or location. These are photographs which, for one reason or another, did not fit easily into Webb’s other geographically-organized projects. The photos are pulled from all corners of the globe—physically displaced, if you will. That’s the methodological explanation, but there is a secondary meaning as well. In Webb’s words, the pictures are “sometimes emotionally, visually, psychologically, culturally” dislocating. Taken collectively and sequenced in a globe-hopping medley, they’re a rootless bunch, stripped of any home base or community. Captions list date and location, but these words seem to be mere formalities. The purpose of the pictures is not to impart vernacular facts. Instead they are vehicles for Webb’s street practice.

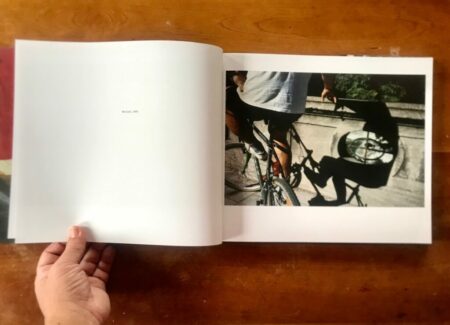

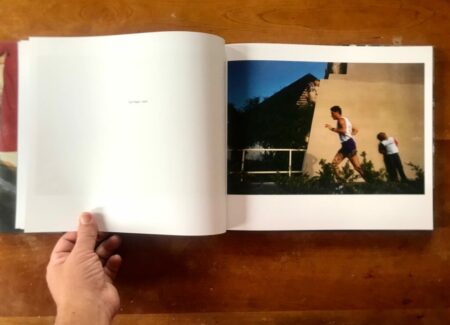

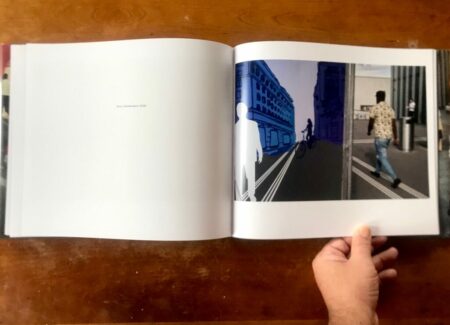

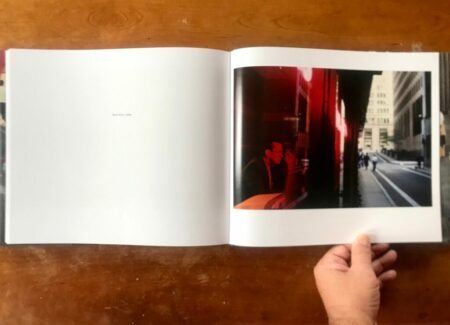

A photograph from Dallas, 1981, for example, may not have much to say about Texas. But it’s a visual tour-de-force nonetheless, weaving proximities of paint, mural, sky, and body parts into a winning frame. Another time-tested classic is included, Webb’s bridge photo from Munich, 1991. It combines a bicyclist, concrete bannister, shadow, and river surfer into a one-in-a-million bullseye. Lest we consider these as lucky accidents, Webb the magician performs the trick repeatedly, right before our eyes. A fruit stand photograph from Brooklyn, 1994 affirms his uncanny knack for layering humans, colors, and distances. A photo of crimson car hoods playing against a pyramid mural lifts Atlanta, 1996 above the Olympic fray. In New York, 1994, Webb demonstrates he can manage mood lighting as well as form. A man in a deep red fog studies the world through a shop window, holding a cigarette. Not much is happening in the exterior street scene before him. Internally it’s a much richer story.

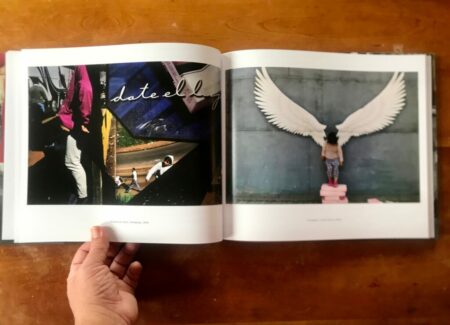

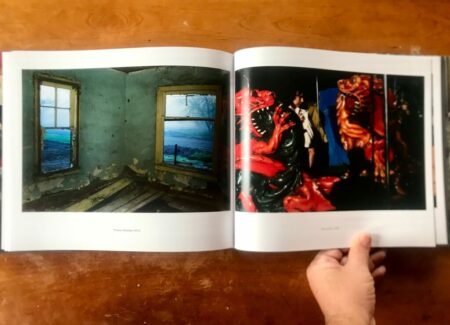

If it seems I’m focusing on old favorites, guilty as charged. But there’s a good reason. These holdovers are the most reliably strong images, forming the core of the book. As for the new additions, quality varies. Some show evidence of a Magnum photographer who, at 71, continues at the top of his game. But others make me wonder. It’s a fine line in street photography between masterwork and failure—whether a split second or a split figure—and several images here fall on the wrong side. A shot of balloons found in Cincinnati, 2022 is rather forgettable, as are two others from the same year, both shot in Bern, Switzerland. I won’t claim that pedestrians juxtaposed with background images are always lifeless. They can offer possibilities, and they’ve been a go-to move for Webb throughout his career (well represented in this book). But at this point, they feel depressingly routine, and even Webb’s vision can’t salvage the Bern pair. Nor can he rescue a scene from South Korea, 2013 of a child framed against an angel wing mural. No need to jet set around the world for such scenes. The same picture is shot 100 times daily in downtown LA. Rubbing salt in the wound, the angel wings share a spread with a much stronger photograph of old, from Ciudad del Este, Paraguay, 1998.

For me this mismatched spread exemplifies the book as a whole. Frankly it’s a mixed bag, an amusing blend of A-listers and B-sides. The idea of dislocation may provide an interesting curatorial framework, but it’s no guarantee of quality. For consistently high caliber work, Webb’s similarly dislocated retrospective The Suffering Of Light (reviewed here) is a better bet.

That said, Dislocations does raise worthwhile questions. Its timespan neatly bridges the millennial era of street photography, from pre-social media to global pastime. Many young shooters now emulate the Webb’s formality, corralling shadows and colors from urban sidewalks. One locale blends into another, and the term dislocations seems increasingly applicable to the genre. Street photographers parachute into cities and festivals, extracting digitized content, with scant long-term investment or attachment. Perhaps they’re merely the leading edge of deeper cultural dislocations. What does it mean to treat the world as personal building blocks? What does it mean to operate in a state of disconnection? Alex Webb has been at it for five decades, with more success than most. Most of his pictures are rooted in place. It’s the others which can teach us something about ourselves. Dislocations is a career marker of sorts. It’s also a touchstone for the wider culture. And that certainly includes street photographers.

Collector’s POV: Alex Webb is represented by Magnum Photos (here), and a variety of galleries including Etherton Gallery (here), Stephen Daiter Gallery (here), and Robert Koch Gallery (here). Webb’s work has little secondary market history, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.