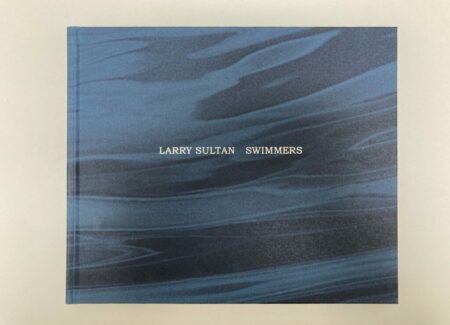

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2023 by MACK Books (here). Hardcover (30 x 25.2 cm), 144 pages, with 66 color photographs. Includes an essay by Philip Gefter. Design by Morgan Crowcroft-Brown. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Larry Sultan’s new photobook, Swimmers, focuses on a lesser known series of photographs he made of people learning to swim in the public pools of San Francisco between 1978 and 1982. With this project, Sultan wanted to confront his own fear of water, as he had had a near-death experience as a child, and the series was inspired by black-and-white instructional images he found in a pocket-sized Red Cross swimming and life-saving manual. “I wanted to do something so absolutely different, and physical, and in a certain way, kind of ill-conceived… I took my camera and went underwater in a bunch of pools. And made pictures.”

While the series was exhibited a couple of times decades ago, the images from Swimmers were largely unknown before the release of this book. According to the publisher’s note, the photobook includes “all the pictures from the series Sultan himself chose and exhibited” and “additional images he marked on contact sheets as well as further selections from his archive which he likely never even reviewed.” Sultan passed away in 2009, and the photographs resurfaced when the artist’s wife, Kelly Sultan, came across a small box of proofs while reorganizing the archive.

Sultan first started making photographs of swimmers in early 1974, in a swimming class for blind people. But he soon shelved the project to focus on a collaborative work with Mike Mandel, which ultimately became their now classic photobook Evidence released in 1977. When Sultan returned to the swimmers in 1978, he used color film, as a friend offered to develop his film for free. The switch to color definitely made the images more painterly and hallucinatory, amplifying their sensual qualities.

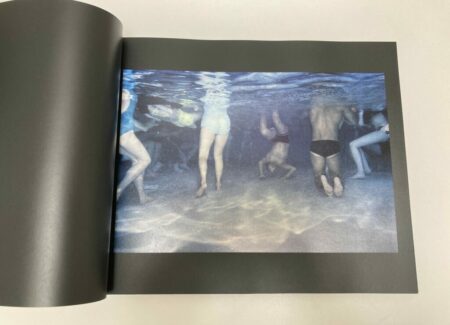

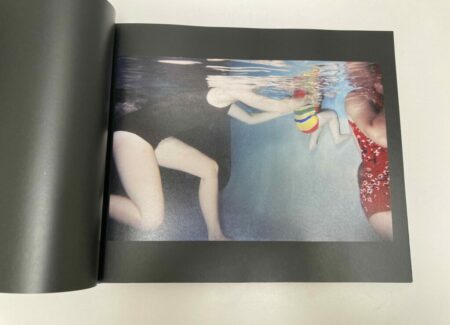

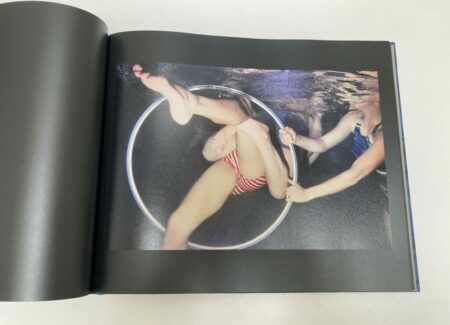

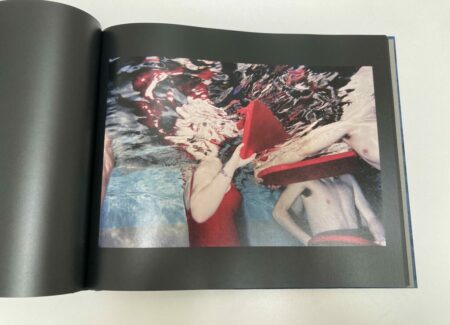

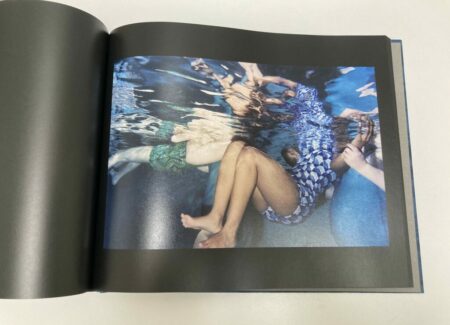

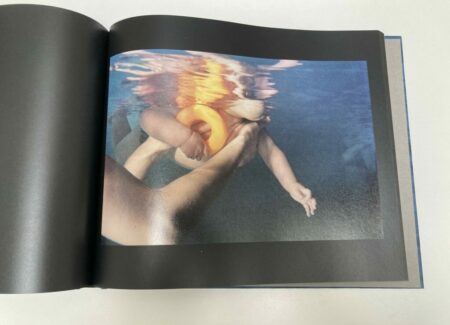

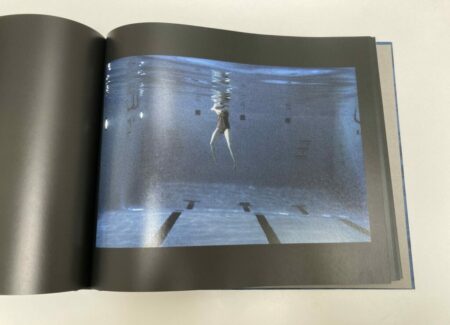

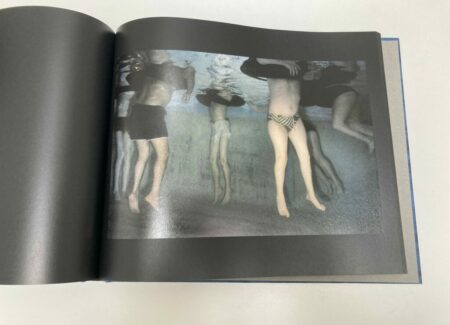

As a photobook, Swimmers is elegantly simple. It is a horizontally-oriented book with an abstract blue cover evoking water movement, and the artist’s name and the title appear right in the center on one line. Inside, the visual flow is consistent – photographs are placed on the right side pages, all against black backgrounds, echoing the underwater settings. There are no captions, page numbers, or other design elements. An essay by photography historian Philip Gefter titled “Deepdiving” ends the book, and it is printed on white paper with a thin black border, connecting it to the main visual flow. Overall, the book is beautifully constructed and printed.

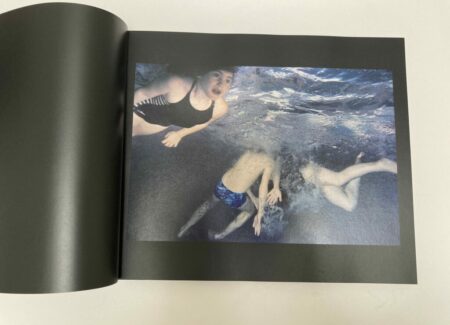

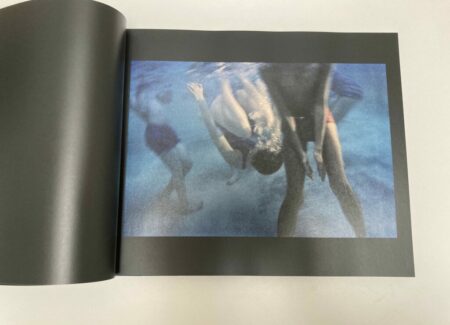

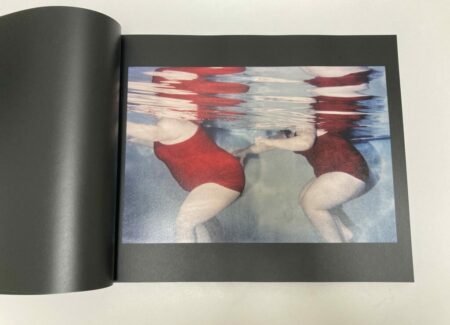

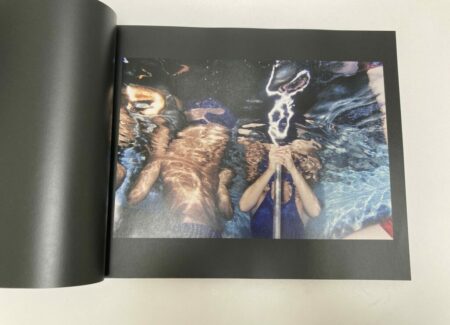

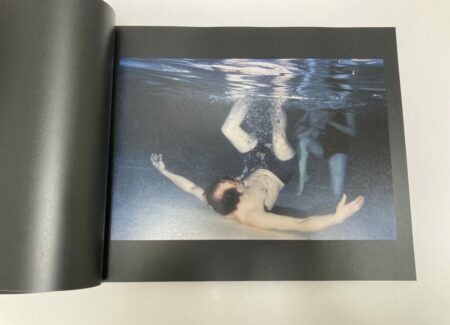

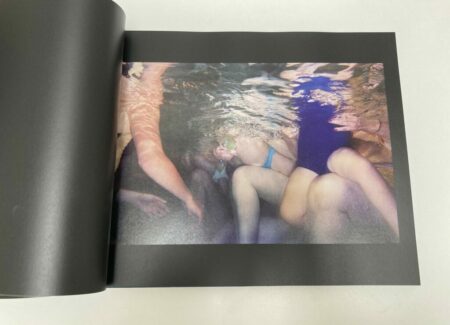

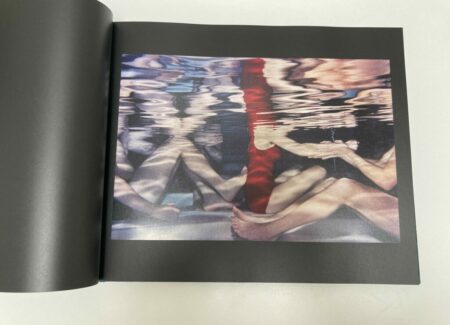

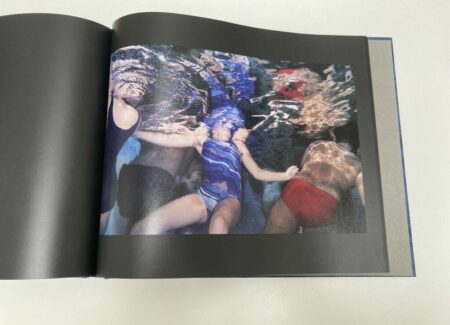

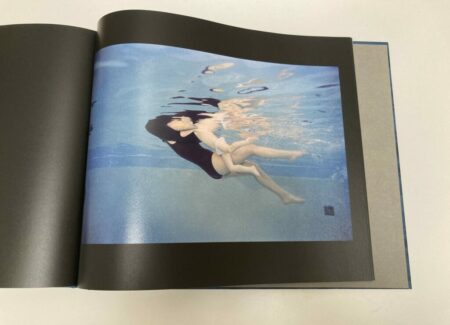

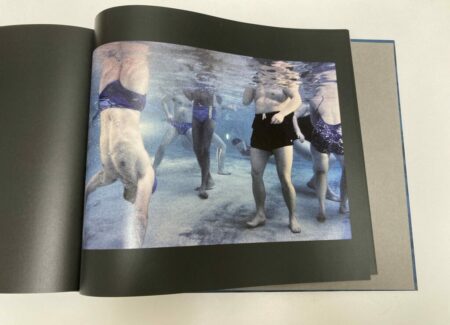

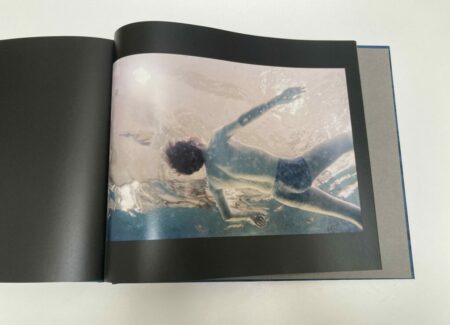

Equipped with a small Nikonos III underwater camera, goggles, and a handheld flash, Sultan would dive underwater and take his photographs of people. There are pictures of parents teaching their kids to swim, swimmers taking lessons with instructors, people standing in the water, and adults swimming and floating on their own. Sultan’s photographs take on a surreal painterly style as the distorted and abstracted bodies float, surrounded by bubbles, reflections, and water movements. In many ways, the series became an exploration of the formal potential of water.

In the opening photograph, a young girl floats in the upper left corner of the image, her eyes and mouth wide open; behind her the limbs of another girl and a boy are caught in a jagged kicking movement. In another image, two women in similar red swimsuits stand in similar poses facing to the left, their heads above the water, with the upper part of the picture capturing their wavy distorted reflection.

While there is a certain degree of muted elegance in movement underwater, some of Sultan’s images also have a splash of humor. One shows six people, most likely learning to swim (they all have black swim rings), as their legs extend in the water. In another, a man holds his breath at the very bottom of the pool, while three boys appear almost on top of him with their heads above the water. The series also features moments of panic, horseplay, intimacy, tenderness, and surprise.

It’s clear that Sultan documented these people in a passively vulnerable state, as they had less control of their nearly nude bodies and facial expressions, and certainly didn’t expect to be photographed while underwater. And while there is nothing inappropriate to be found in these photographs, there’s still an element of voyeurism here, providing access to something usually hidden from view. In our contemporary world, an anonymous man with a camera making pictures in a public pool wouldn’t likely be tolerated for long.

But photographers have always been drawn toward pools and the distorting aspects of water. Jodi Bieber’s photographs capture the chaos of a crowded pool, while Nan Goldin photographed couples making love in swimming pools and Deanna Templeton photographed her friends skinny-dipping. The recent book Pools edited by curator Lou Stoppard celebrated “the joy and enduring allure of the swimming pool”, bringing together a wide variety of photographers and image-making approaches.

The very last photograph in Swimmers shows a boy floating in the water looking up, and this is the only time Sultan shows the world from outside the swimming pool. In his essay, Gefter describes the series as “a transitional body of work in Sultan’s oeuvre,” noting that it had an important influence on his other projects, particularly his now iconic “Pictures from Home”. So while Swimmers is certainly a secondary body of work in Sultan’s long career, it’s a surprisingly engaging and solid photobook, offering both a handful of standout images and a few understated insights into Sultan’s evolving photographic eye.

Collector’s POV: Larry Sultan is represented by Casemore Gallery in San Francisco (here), Yancey Richardson Gallery in New York (here), and Galerie Thomas Zander in Cologne (here). Sultan’s work has only been intermittently available in the secondary markets in recent years, with recent prices ranging between roughly $5000 and $35000.