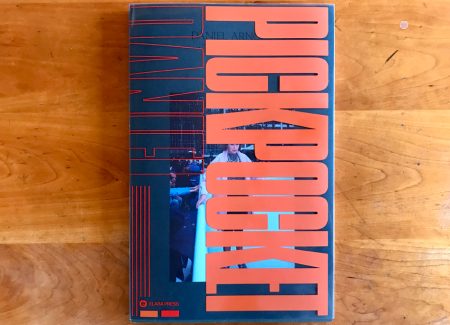

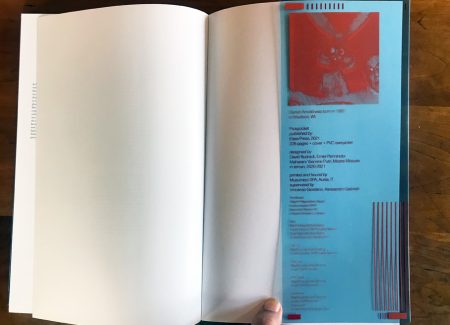

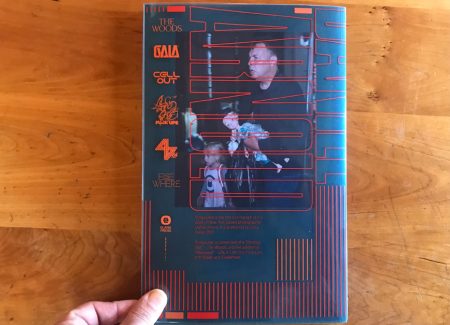

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2021 by Elara (here) Textured softcover with screenprinted mylar clear outer jacket, 302mm x 195mm, 228 pages, with 5 individually bound inserts at offset width. Includes a total of 578 images, with extensive notes by the artist and an afterword by Josh Safdie. Designed by David Rudnick, Emiel Penninckx, Maharani Yasmine Putri, and Mozes Mosuse in Terrain. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: The career of New York street photographer Daniel Arnold has been roughly synchronous with Instagram. The platform was founded in 2010, and began to escalate rapidly in 2012 after its acquisition by Facebook. In its nascency, Arnold was an early adopter. He’d been shooting for a few years at that point, and Instagram seemed a natural outlet. He quickly found an audience there, and it has since grown steadily, currently sitting at around 340,000 followers. With its thumbnail sketch by Jason Polan, Arnold’s IG visage has morphed into a street photo brand of sorts. He has a mustache and wool cap. He shoots a G2. All have spawned imitators.

Visit Arnold’s website today and it feels rather derelict, with an OUT OF DATE / UNDER CONSTRUCTION tag heading various archival material. Instagram is where the action is, although his account has slightly cooled during the pandemic. It’s not merely a blank vessel for sharing – its very form is central to his process. Instagram requires no gatekeeper, no expense or training, no RGB calibration or fussy print specs, no conceptual requirements beyond the simple act of daily observation. If problems and imperfections abound, they merely reflect reality. The world is funneled daily into a small box, then thumbed, liked, scrolled, and soon replaced by the next fleeting image. Street photography fits this form like a glove.

Arnold’s burgeoning career enjoyed a burst of fuel injection with a one-off print sale in 2014. Pitching 4 x 6 prints on Instagram, he struck an unexpected windfall, netting $15K overnight. Hey, maybe there was a future in this Instagram thing after all? Attention begot attention, and virality ensued. Unperturbed, Arnold kept shooting and posting. He began taking on commercial gigs and assignments, but the core of his practice remained self-directed, street photos encountered in passing.

At this point, his work is so closely associated with New York city that one might assume he’s a native. But Arnold grew up in Milwaukee and lived there through his early 20s before moving to New York in 2003. “I knew three people in town,” he writes. “In 2003 common knowledge said I’d just missed New York. But isn’t that always the case? In a city whose whole restaurant lineup changes before you get back from the bathroom one true thing is that you missed it. I felt that from the start and said damn I need a camera. Got busy making proof for the next wave that they were too late, even if that’s a big scam.”

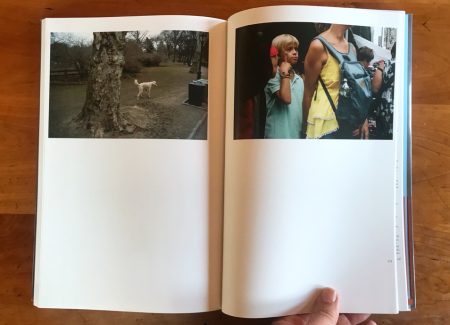

The cynical breeziness of this short passage is typical of his writing style, weaving personal timeline, misplaced nostalgia, and photographic raison d’être. It feels jotted quickly in dismissive offhand voice, as if dropping a poem off at the drugstore for processing. “These are Rorschach captions,” he explains. “I have no agenda. I’ve just been looking at the photos and reacting on the spot.” His photos follow a similar mold. A picture might capture part of a pedestrian’s lips and off-kilter background, or a man in a park sprawled on a bench, or a boy coyly fingering an F-bomb against his cheek. “One way to look at the larger body of my work,” explains Arnold, “is as a collection of instances where my thoughtful mind was unavailable. The art of the basal ganglia. Survival brain.” Many are shot from the hip, spur of the moment. Arnold: “I get zero satisfaction from crafting a pictures, got zero interest in control or direction.” If his exposures are not deeply considered, they resonate with scattershot intensity. In their zeal for humanity and observational obsession, they have a sociological bent: people as solvable puzzles.

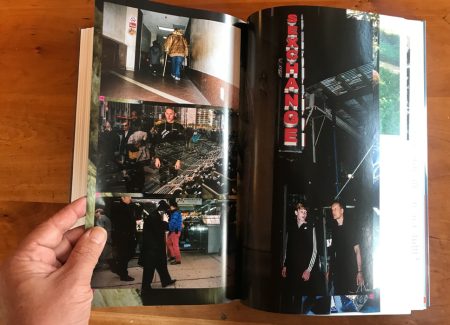

If the style appeals, Arnold’s recent monograph has plenty in store. The book is called Pickpocket—a sneaky steal of a word worn as a street shooting badge of honor—and it’s packed with over 500 photos. These include a few frames from his 2016 book Nassau Avenue (reviewed here). But for the most part, none have been published before in book form. Even better, most come with extensive annotations. They describe the shot logistics. Taken as a whole, and almost as an afterthought, they do a fair job narrating Arnold’s bio. They recount his path into photography, his thoughts about the medium, and life in general. All this while hopscotching across the years—from 2008 through 2020—recalling specific dates and addresses with astonishing accuracy. I must say I’ve slogged through many boring photography book texts in my time. Pickpocket‘s is a happy exception. Arnold (a former copywriter for Nickelodeon) sparkles as a writer, with captions falling somewhere between seen-it-all barfly and wisecracking Big Apple Daybooks.

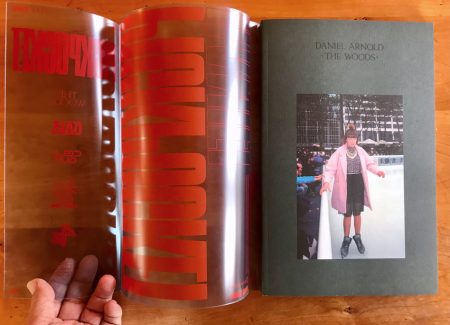

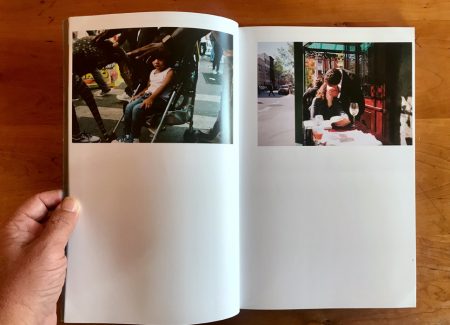

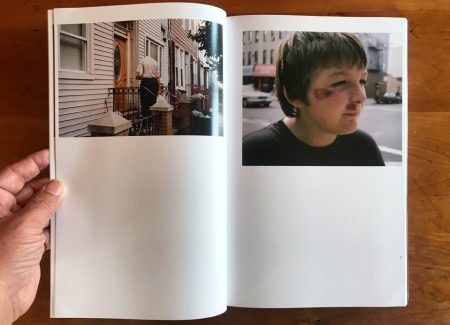

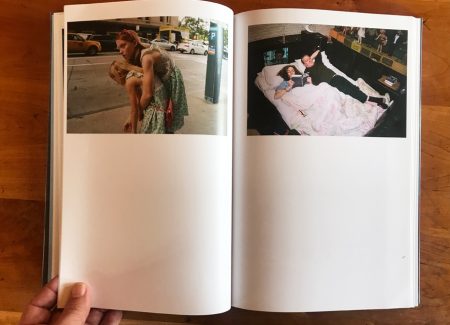

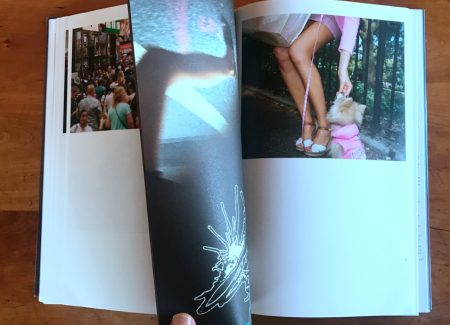

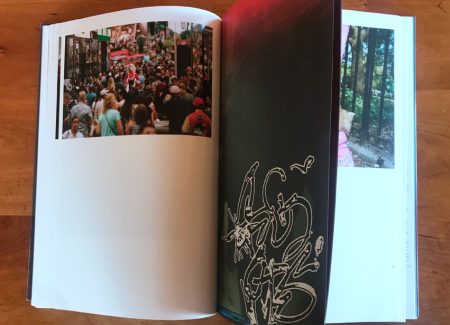

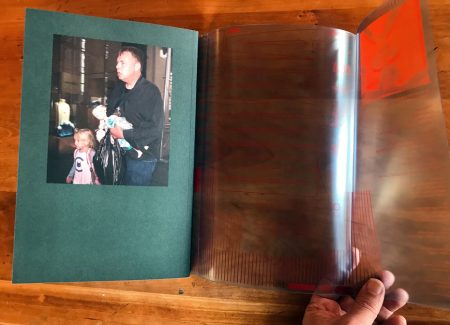

But that’s just the afterword. Before getting to that point, there is the book itself. By any measure, it is an odd duck. It is strangely oblong, for starters. The photos in its main section are shot in landscape format, then tucked in the top half of vertical pages above wide swaths of white space. This core is called The Woods and it comprises the book’s “Prestige Edit”.

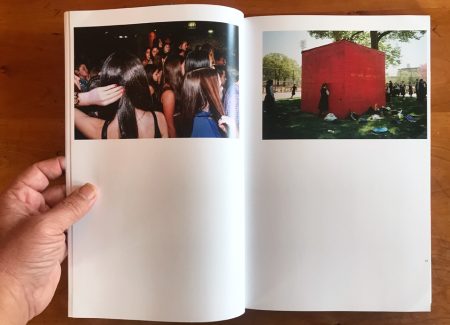

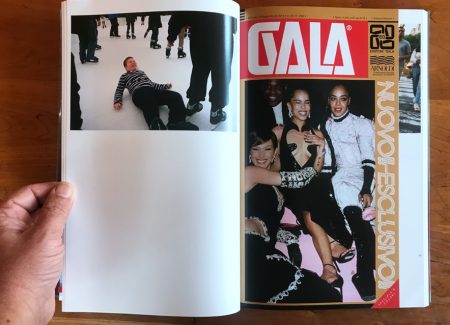

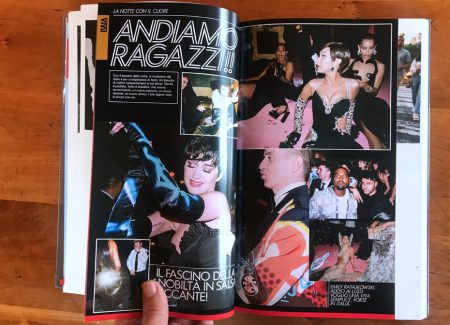

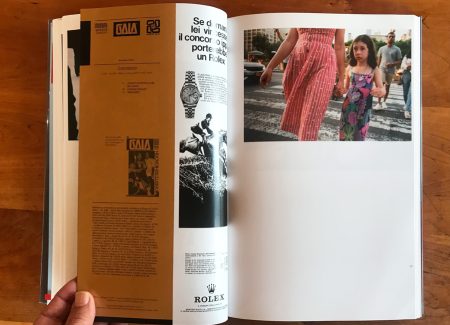

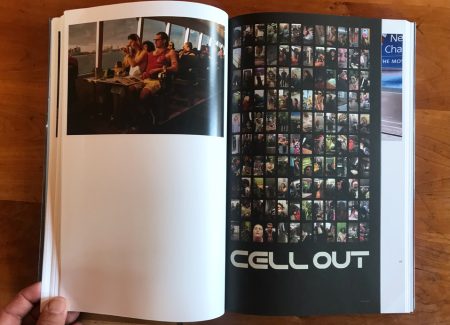

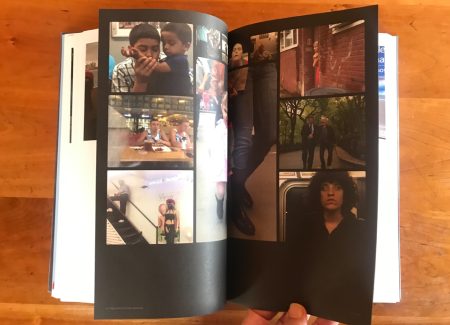

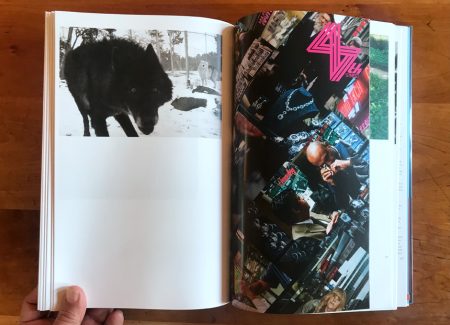

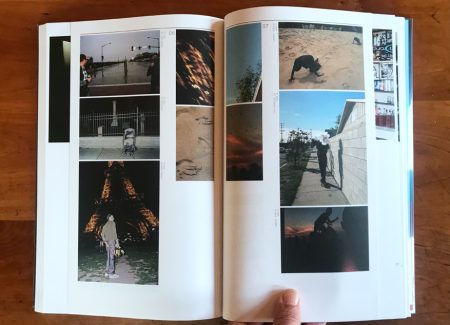

Tucked inside are five additional “Alleyways”. These are thin zines spaced twenty pages apart through the central section. Although ostensibly “less prestigious” than The Woods, the photos are essentially similar. However, the layouts are different, generally smaller and more crowded. Each “Alleyway” has a unique design, typography, paper type, and focus. Taken in order: Gala shows glossy spreads from fashion shows, with text in Italian. Cell Out displays iPhone photos on black matte paper, shot in candid street style. Fuck Ups is just what you might guess, misexposures, light leaks, and accidents. 4th Street focuses on the Diamond District on 47th Street in Manhattan, an area which gave even Bruce Gilden trouble, but which Arnold reportedly navigated without incident. Lastly, Elsewhere collects photos shot beyond New York City. Most are from the US, but they extend as far as Morocco, Greece, and Liberia.

With The Woods and 5 interior zines, Pickpocket is stuffed to the gills with photos. There is no letup, and the book feels overwhelming. At first I was put off. Surely it’s a photobook truism to edit ruthlessly? Kill your darlings—that’s bookmaking 101. But after spending some time with Pickpocket, there is a method in the madness, and I forgive Arnold his excesses. This book embodies the wall-to-wall experience of living in New York City. The metropolis is in your face at all times, and so is Arnold. It’s only natural that his book feels the same.

Like an old time New York street character, Pickpocket has other endearing idiosyncrasies. The whole package including pictures, inserts, and end notes is perfect bound in a softcover book, wrapped in a cyan mylar dust jacket. With bright orange lettering spelling PICKPOCKET DANIEL ARNOLD along with chapter headings and other notes, it is quite unlike other monographs. It feels more like an airplane safety manual in the hand. But its odd nature hasn’t diminished its prospects. Like Arnold’s print sale, Pickpocket has been a viral phenomenon, selling out two months before publication.

If the design is an outlier, it may be because it’s published by a movie studio. Elara is a publishing subsidiary of Elara Pictures, the production company of filmmakers Josh and Bennie Sadie. To the best of my knowledge, this is Elara’s first and only photobook. But the connection is less of a stretch than it might seem. If Good Time or Uncut Gems had a still-frame equivalent, it might look something like Pickpocket. The Safdie brothers are fans. They’ve used Arnold as an informal casting agent, sometimes finding actors through his pictures. They’ve invited Arnold to shoot on recent sets. “Daniel’s the human paparazzo,” writes Josh Sadie in the afterword, “The bipolar nature of his work compounds itself to a form in a new chaos: a certain type of catastrophe.” So an Elara monograph was not completely unexpected. But the process had some wrinkles. “They wanted an edit of my photos that were movies,” recalls Arnold. “That was a classification they came up with and I wasn’t totally sure what it meant, so I adapted it to mean instances of our New Yorks intersecting….Sweet tragic hustler muscler Safdie city, stepping into my subverted sentimental mystery coincidence Americana.”

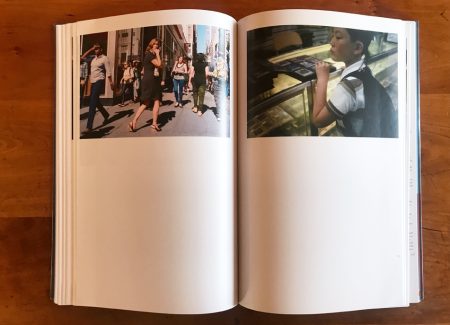

What subverted sentimental mystery looks like in practice is basically people captured in situ. There are few nonhuman frames in Pickpocket. Within that basic parameter, the variety is impressive. He may be based in Brooklyn but Arnold seems to bounce around all boroughs at all hours. There are interiors, park shots, photos at night, dusk, and day, in bars, bus stops, downtown, suburbs, and of course plenty of pedestrians on sidewalks, the bread-and-butter of any NY street photographer. Somehow he manages to track the exact location and date of each exposure, a tough task amid the daily rough and tumble of shooting, especially with film, which does not record metadata.

With photos hopscotching locations and timelines, Pickpocket has an impressionist quality, more flâneur’s sketchbook than masterpiece. It’s a perfect fit for Instagram, but in book form, pictures naturally assume more gravitas. Presumably these several hundred were printed out for a reason. Perhaps feeling the weight of finality, Arnold strives to keep perfection at arm’s length. Even the final edit is fluid. Self-deprecating captions emphasize its half-baked quality. March 2017 at the corner of 40th and 7th. This photo has always struck me as nothing special…February 2019 at the Ducks Pond in Central Park. To me this one kinda sucks. But don’t let me spoil it for you…July 2018. The photo never did for me what it seems to do for others…October 2014 on the subway. Always felt that something was off about the color here, but I have no idea what it is or how to fix it. I’m generally interested in letting go.

It’s rare for a photographer to express doubts so openly, and a canny way to earn trust. By unloading his misgivings Arnold pulls the reader into his corner. Once there he can unveil deeper problems, for example: September 2018 in Cleveland, Georgia. I can’t believe how long it took them to kick me out of this place…May 2013 at Amerind Cafe on Manhattan Ave. I put the camera to my face and this woman exploded out of her car screaming…August 2019 on Spring between Broadway and Crosby. If you follow the lady’s hand, you can faintly see how I got away with this one, but my explanations end there. I’m no physicist. A photo shot from the hip of a girl at 14th and Union Square carries a particularly revealing caption. “Up there they can’t conceive, when they catch you belly shooting, of any purpose beyond creepiness, because pure curiosity doesn’t quite compute in the grown-up zone. Up there, romance is a sex word. A couple feet down it means wonder.”

Setting aside creepiness, romance, and wonder for the moment, a primary difficulty shooting from the belly (or hip) is that one can’t see through the viewfinder. The method naturally results in a lot of garbage frames. In some ways this is just another difficulty inherent to street shooting. Any process that relies on chance and serendipity will produce varying results. Hip shooting merely lessens the odds further. If a frame doesn’t work out, there is always the next one. And yet good photos do come in time, especially to someone as active as Arnold. Pickpocket contains several dozen clear winners. A kissing couple caught in a perfect chiaroscuro of shadow, for example, or a woman engulfed in the aroma of a newspaper cone. A kid flopped over on his amusement ride is a perfect catch, as is a 6th Avenue encounter with arms, limbs, stroller, and crosswalk. To be sure, there are lesser frames too, as in any book with this many photographs. But they don’t detract much. The variance of quality provides a fitting vehicle to showcase Pickpocket’s ever fluctuating scenes, and Arnold’s roaming eye. The book’s design might bring some to question the very goal of “good” photography. Perhaps the magic lies in the process. The continual hunger for new pictures might be enough.

Arnold hints in this direction with his annotated captions. They veer more into philosophical territory as they go, eventually negating themselves.“Between you and me, at the end of a marathon of captions: if it requires an explanation it’s probably not a very good photo. If it begs for one, that’s a different story.” If that sounds vaguely Winograndian, other captions hew even closer. “I prefer not to exist, if possible,” he says at one point. Elsewhere, while shooting sheep’s meadow in Central Park: “I still prefer a self-contained world that doesn’t acknowledge my existence. To be invisible.”

That may be the ultimate street photographer fantasy, but of course it’s impractical. And publishing a monograph would seem to be a major step toward existence, away from invisibility. So Pickpocket is an affirmation of sorts. It joins a long history of street photography monographs, many targeting New York City. A crowded field! But there is enough here to distinguish Pickpocket from the pack, and to make it worth seeking out. The unusual design and sheer volume are distinctive. The rush of images is quite contemporary, a cousin to Instagram and social media. The annotated notes are as engaging and informative as any monograph. Taken as a whole, this book has pulled Arnold from the woodwork and placed him in the spotlight for a moment. He can go back to being invisible in due time. But for now, Pickpocket deserves a look.

Collector’s POV: Daniel Arnold does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. As a result, interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artist via his website (linked in the sidebar).