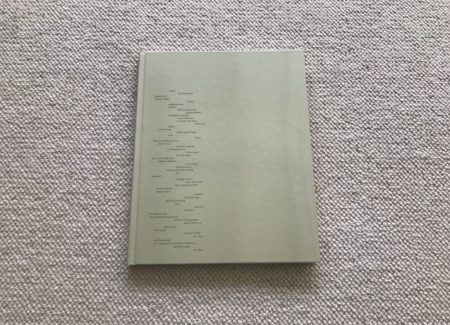

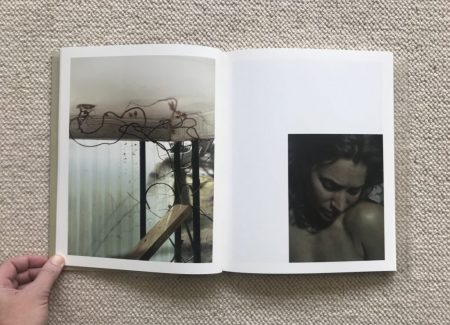

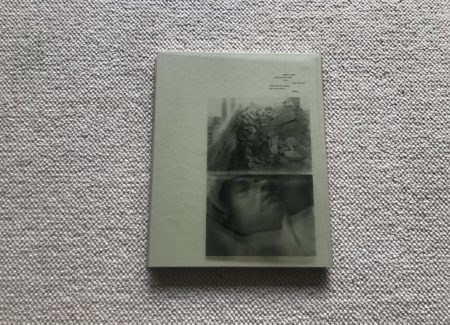

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2020 by MACK Books (here). Hardcover with PVC printed jacket (30×24 cm), 96 pages, with 13 color and 47 black and white reproductions. Includes texts by the artist. Design by the artist and Morgan Crowcroft-Brown. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Deciding to embark on a photography project dedicated to the idea of “home” is riskier than it might seem at first glance. Of course, “home” is often right in front of us, so it’s a potentially handy subject, and one we likely know well already. But in that familiarity lies the challenge – “home” can also feel like an idea that is on the verge of being tapped out, done to the point that its discoveries can feel hackneyed and obvious, full of traps and clichés that threaten to bore us with their sentimentality.

In the right hands though, the concept of “home” is still untidy, very much filled with rich human complexities, contradictions, and relationships worth exploring – it can be people (like family, friends, and neighbors), places (houses, but also cities, wilderness, and everything in between), and specific objects, or more ephemeral things like atmosphere, presence, routine, emotion, and resonant memory. While each of us feels home differently, a sensitive, in-depth study of one person’s definition of home can end up being both highly individual, and somehow plausibly universal.

For Raymond Meeks, it was a move that drew the concept of home into clearer view. At its core, relocating to a new house is a process of exhaustive sorting and separation – deciding what things come forward into the new life and what is left behind, and in a sense, getting a chance to redefine who we are and what we value. For Meeks, the process was complicated by the combined households of his partner, Adrianna Ault, and her two daughters, so there were several competing priorities and versions of “home” in the mix. The process ultimately became the subject of a long term photography project for Meeks, first taking shape as a small self-published 2018 photobook of carbon prints on repurposed book paper. The book took its name ciprian honey cathedral from oblique words found inscribed on the back of an abandoned dresser, and the project extended to include not only Meeks’s house and family (in the midst of upheaval and change), but other empty houses in and around upstate New York where he lives.

This recent photobook (with the same title) builds on and reimagines that first effort, taking a few of the original images and surrounding them with many more made since, in both black and white and color. The result is a book with a wholly different balance, with less of a feeling of imminent transition and upset (the move) and a deeper sense of settling, where the rhythms of home have been reestablished and now attentively observed.

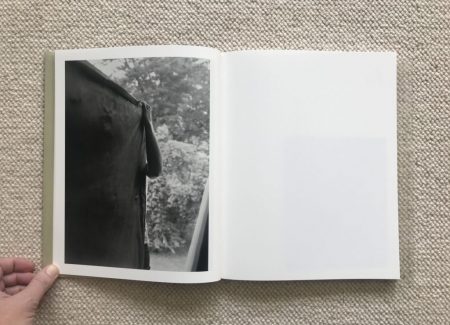

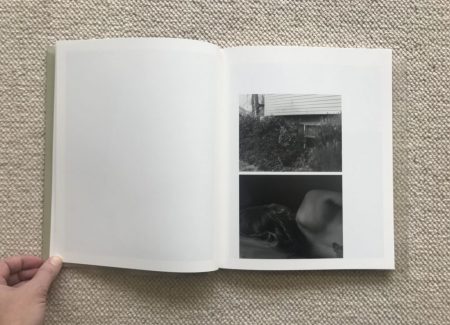

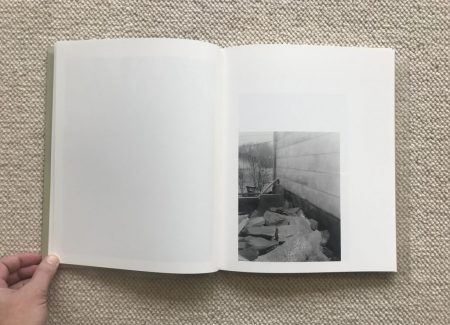

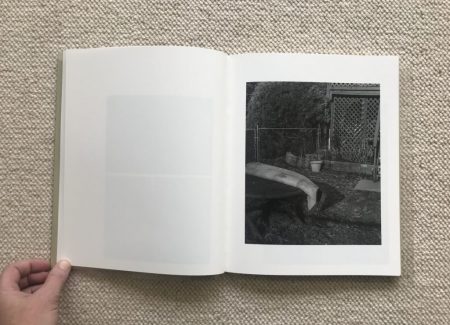

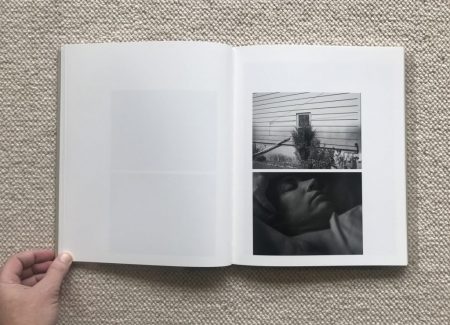

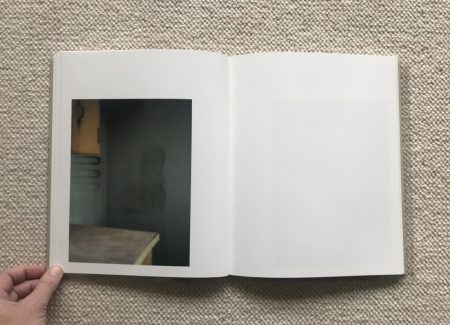

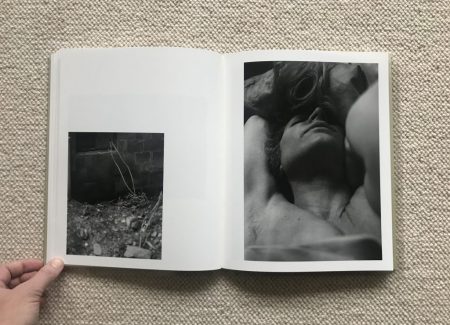

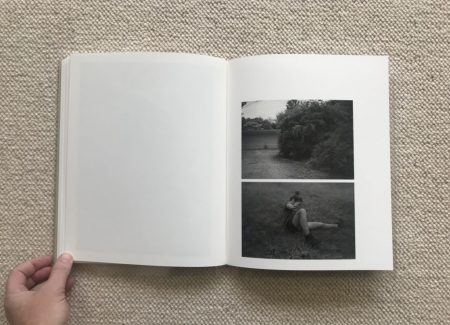

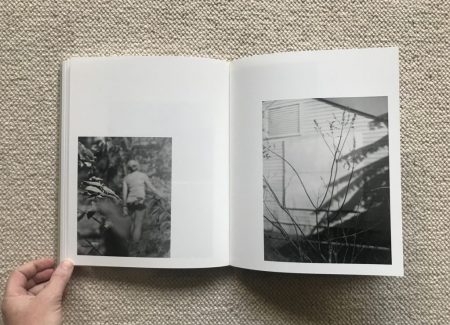

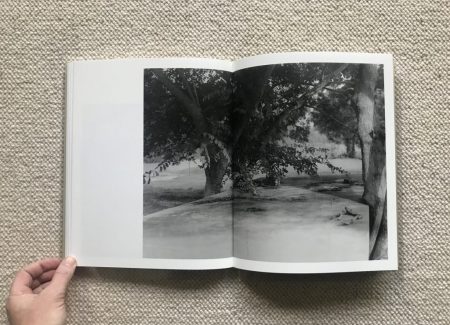

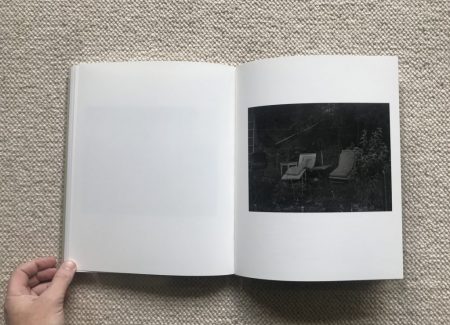

Roughly half the images in this ciprian honey cathedral document the surfaces, textures, and details of home, in this case broadly defined to include not only the specific Meeks house but any number of other empty and anonymous houses and yards that share a similar geography and mood. A quick flip of the photobook would almost certainly lead to the conclusion that these are consistently unremarkable spots. Forgettably scraggly bushes and hedges surround the house and hide the foundation. There’s a tree in the front yard. Out back, there are things better hidden from the view of the street – piles of broken cement blocks and rocks, random construction debris, pipes, a patio table holding a rolled up carpet, a sink hole near the corner of the house, angled wires that climb up the siding, and a garage partially obscured by overgrown bushes. Further into the nearby forest, Meeks shows us shady private nooks with mismatched lawn chaises and rotting cushions, an old swing hanging from a tree, and an aging barbecue that has seen its better days.

But Meeks finds quiet poetry in nearly all of these details – his attention (and the lusciousness of his tonalities, particularly in color) makes us look again. Once we’ve slowed down a bit, what emerges is that each of these overlooked finds is infused with intention. Someone planted that bush (and the thin plants next to it), painted the shutters green, tossed those rocks back there, built that trellis, and set up the chaises, and this is where the “home” we’re in search of actually lies. Even though they are not our memories, we can see that they are someone’s (maybe even Meeks’s), and that there are embedded stories, anecdotes, and family lore potentially tied up in all of it.

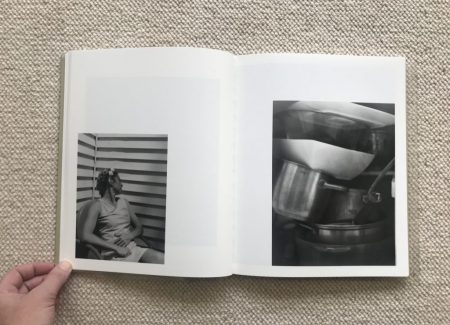

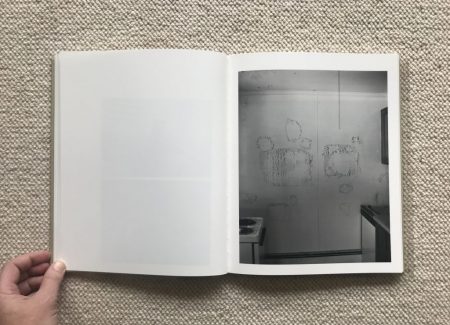

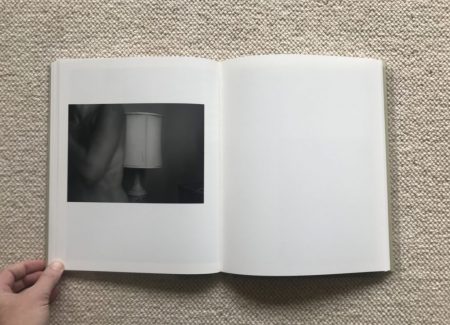

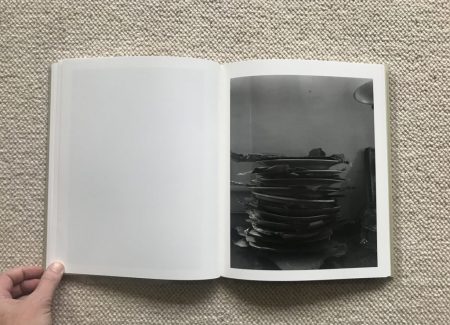

Inside the house, there is a muted stillness that pervades the space. Evidence of moving is still to be found here and there – stacked plates with paper between them, peeling paint once covered by something hanging on the wall in the kitchen, piled up pots and pans, a grease stain now exposed on the wall – with the rhythms of home momentarily interrupted and rerouted. Other makeshift solutions, like curtains bunched up to let the light in and a 2×4 used to brace a corner where vines creep in underneath a gutter, feel either temporary, or so ingrained that they are now left as accumulated normal.

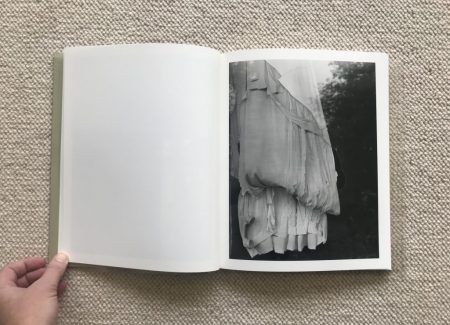

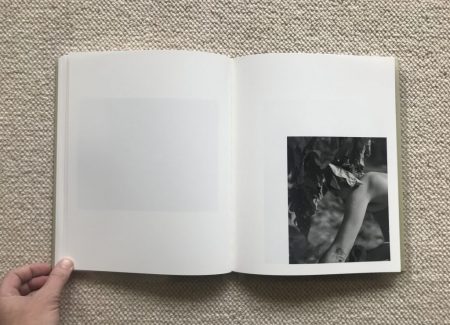

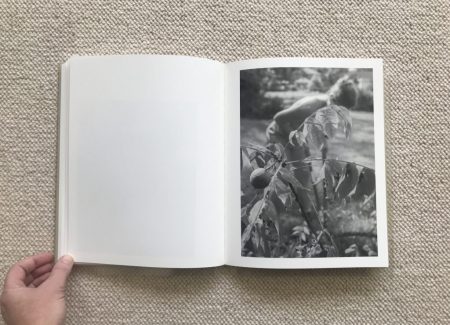

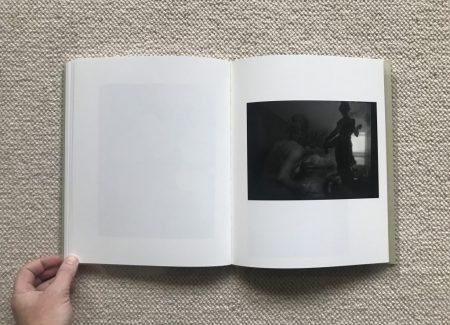

A different definition of home doesn’t root itself in resonant places or historical objects – it’s simply wherever your spouse or partner is, the idea being that the place doesn’t matter much as long as you’re with the one you love. In this way, ciprian honey cathedral is a straightforward love story, with Meeks’s partner Adrianna at the nexus of his world. In conjunction with the process of moving, we see Adrianna hoisting what looks like a mattress, in the basement with boxes and furniture, and up in the attic with a gracefully swaying statue. More often, Meeks captures her gestures and movements as the motions of ordinary life – she folds laundry in her bathrobe, picks up clothes left lying around, and repeatedly works in the garden, digging, walking, working, and even playfully falling down, screened by leaves and ripe fruits. These pictures are filled with gentle shared domesticity, the kind where one partner notices and appreciates the labors of another, while also seeing the fleeting moments of elemental grace that can be found in these overlooked routines.

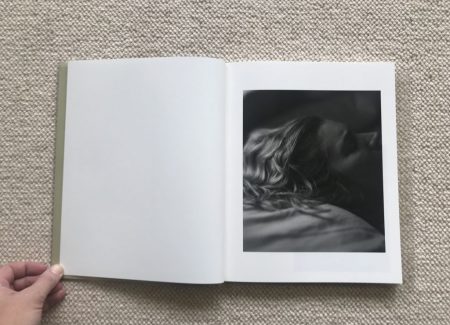

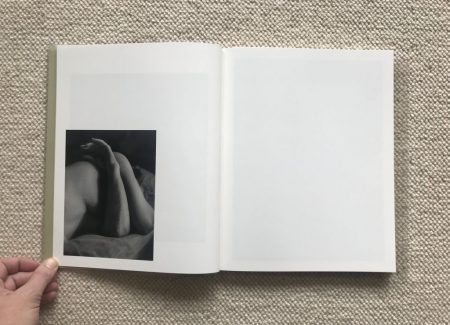

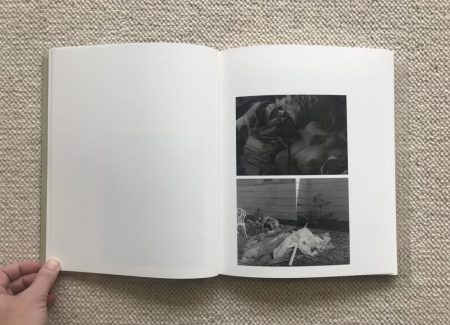

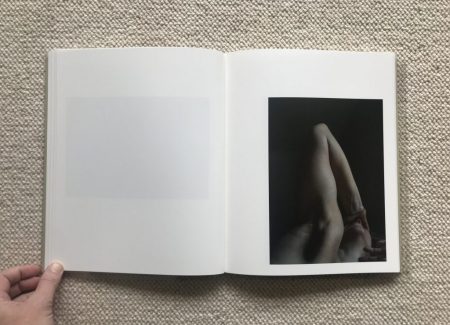

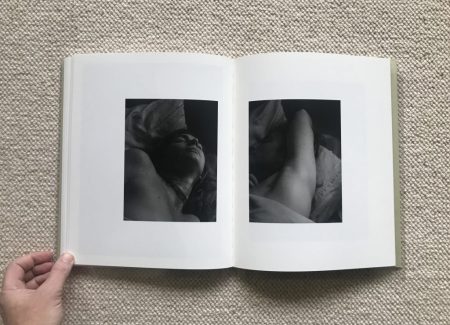

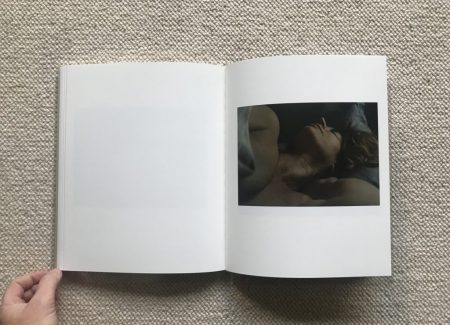

Even more tender and affectionate are Meeks’s portraits and nudes of Adrianna in bed in the morning, asleep or at least dozing. These images provide the underlying structure of the book – it’s where we start, where we end, and her presence is felt intermittently but persistently in between and throughout. While Meeks’s photographs are recent, they dig their aesthetic roots in the photographic soil of the late 1960s and early 1970s, particularly the nudes and portraits of Imogen Cunningham (especially Phoenix Recumbent) and Emmet Gowin (of his wife Edith).

In the pure, shadowy light of the morning, Meeks watches Adrianna, capturing the subtle nuances of the texture of her hair, the bend of her arms, the turn of her shoulder, and the highlights that dance across her nose, lips, and chin when the light is just right. A few of these moments are undeniably lovely, understated photographic knockouts filled with calm repose and dreamlike vulnerability. Meeks thoughtfully uses soft blur and the veiling effect of a nearby plant to make his views more indirect, and his attention to the folds of drapery and the tactile scrunching of sheets adds further interest to his images. The photographs feel relaxed but intimately caring – it is clear that Adrianna provides Meeks a sense of comfort, and his pictures celebrate and repay that mutual kindness.

The only text that accompanies the photographs begins on the front cover, continues across one spread near the end of the book, and finishes on the back cover. It is a “text collage” by Meeks, a flowing poetic tumble that incorporates the words in the book’s title, as well as a range of small memories and personal anecdotes. It is both descriptive and allusive, filled with fragments only those involved might entirely understand or remember, with a romantic air of shared everyday secrets.

Meeks has already long ago proven that he can smartly craft projects into memorable photobook objects, and ciprian honey cathedral continues his winning streak. It is intimate, observant, meditative, and heartfelt, in ways that draw us into the tiny details of a particular life. And more broadly, it reminds us of what a photographic valentine should be – attentive without being precious, emotional without being cloying, and authentic without trying too hard to be convincing.

Collector’s POV: Raymond Meeks is represented by Casemore Kirkeby in San Francisco (here), Charles A. Hartman Fine Art in Portland (here), and Galerie Wouter van Leeuwen in Amsterdam (here). Meeks’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.