JTF (just the facts): Published in 2021 by MACK Books (here). Embossed hard-cover with tip-in (17 x 24.5 cm); 72 pages with 37 monochrome and 4 color reproductions. Includes texts by the photographer and Abigail Meeks. Edited by Adam Meeks. Design by Raymond Meeks, Adam Meeks, and Morgan Crowcroft-Brown. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Also available as a signed and numbered limited edition of 150 copies, including a silver gelatin print hand tipped-in to the front cover, and a unique drawing, inserted into the back endpaper.

Comments/Context: A somersault is a movement in which a person turns head over heals and lands on their feet. For children, it is one of many ways by which they learn how to gauge distance and gravity, how to trust the space that surrounds them and the small bodies they inhabit. As their bodies grow into young adulthood, this playful exploration of possibility slowly settles into an awareness of boundaries – their own, and those imposed by others. Then it dawns that a once unbound movement, a somersault, has stalled into metaphor: into a state populated by doubts and questioning, where grounds shift and balances are off. Parents tend to call this realization a phase, rebellion, or coming-of-age, and they know that only by leaving and breaking away, eventually, their children will find their feet again. It is within this threshold of tension and suspension, awaiting the leap of departure while holding onto what is dear, that Somersault, the new photobook by Raymond Meeks, so gently unfolds.

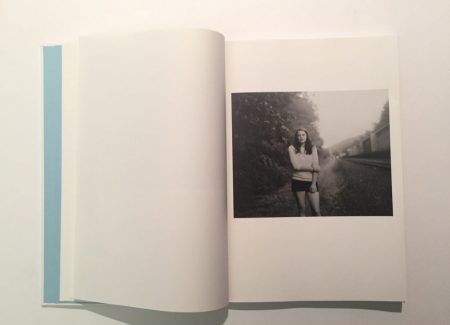

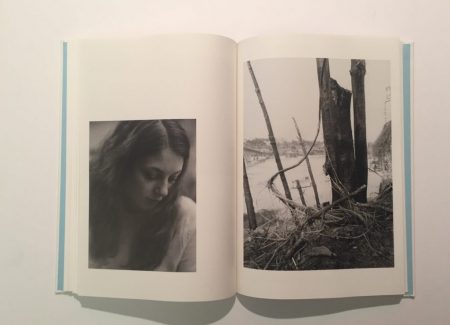

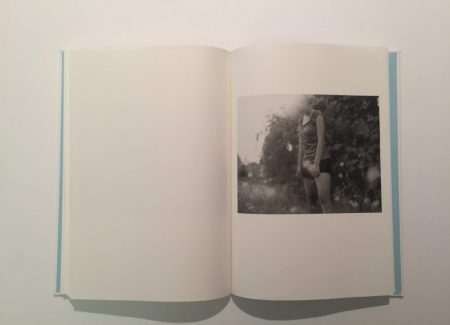

For Meeks, the transitional moment, when “a daughter ceased trying to please her father,” as he writes in a short accompanying text, arrived as “unannounced” and “without advance warning,” as for any parent. Unlike many, he was able to capture these moments in a series of delicate black-and-white portraits – perhaps most revealing in the photograph reproduced on the book’s cover. In it, we see his daughter Abigail (Abbey) dressed in jeans and a cardigan, facing the camera. Caught under a canopy of haze, she stands in a lot overgrown by suburban wilderness – a somewhere in the middle of nowhere, beautified by a blooming bush of roses. I look at her hand nudging the petals of one flower, her legs suspended in counterpoise, her slightly leaning shoulders, and notice the breeze that drifts through her hair, while everything else is dauntingly still. Within this stillness (a signature of Meeks’s photographs), small details continue to accumulate – painted toenails in worn-out flip-flops, a little dimple on the chin, the slow curve of her waist. And through these details, Abbey asserts her presence: a presence that appears both ancient and newly found – that is so inevitably physical, the frame, and landscape, can barely corral it. Among the many portraits, which are at the heart of this book, this is the only one in which her eyes meet the lens directly. But her gaze remains impenetrable. What does it take for a father, I wonder (while thinking of my own), to reconcile the sight of his daughter, the girl, becoming a woman?

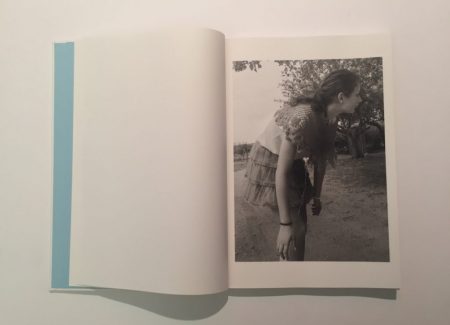

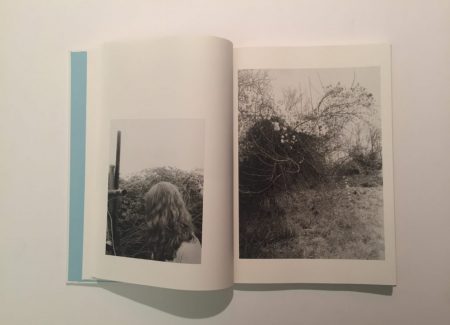

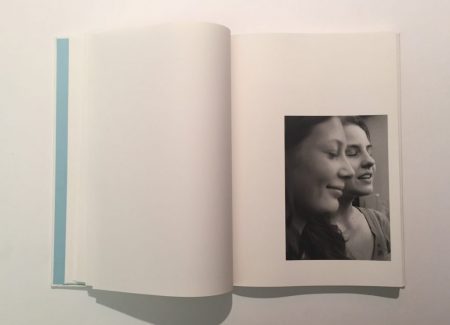

Having photographed his daughter from a young age, out of curiosity and investigation, to spend time with her and get to know her more, perhaps differently – it seems that Meeks has found a way, at least visually, to grapple with mystery and embrace the ambiguous and unresolved. In Somersault, we can see that in the often-fragmentary nature of Abbey’s images, when her face is obscured by the profile of a friend or a lock of unruly hair; when she turns her back; when her eyes are closed, lost in thought, or directed elsewhere. No matter how long we look, she won’t give herself away. What we can sense, however, is what unites these seemingly disparate photographs: a persistent search for meaning in visibility itself and the essence it might reveal.

This quest is no stranger to images of children on the cusp of transformation. Think, for instance, of the photographs by Sally Mann or (in respect to Somersault, perhaps, more synchronous in timing and spirit) of Sian Davey’s Martha – a photographic journey documenting her sixteen-year-old stepdaughter over the course of three years. As I look at Davey’s portraits – observing the kaleidoscope of gazes exchanged between two women – to better grasp the ones taken by Meeks, I understand why this comparison is infallibly slanted. Both photographers dive into the psychological landscapes of intimate relationships. Yet, while Davey’s appear as mirrors of female reciprocity, Meeks’s seem like a reflection of fatherly longing and amazement.

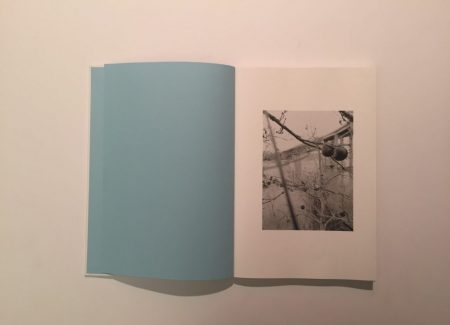

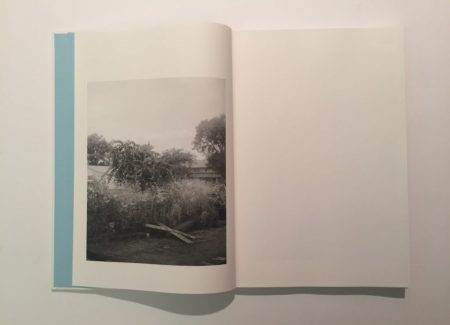

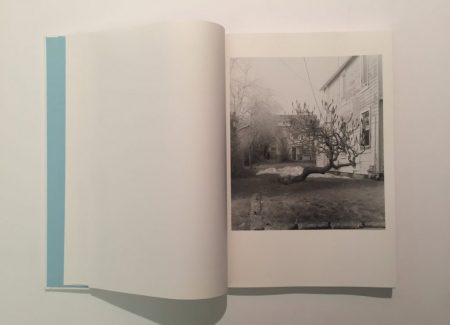

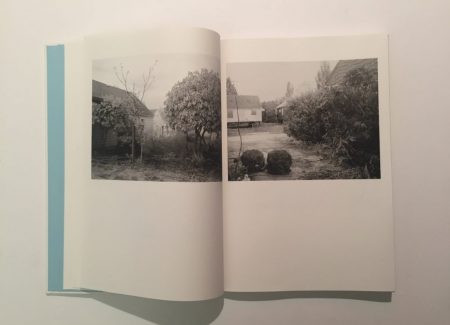

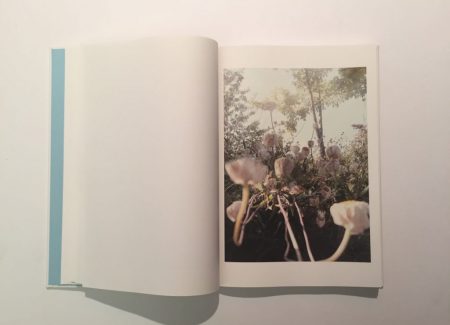

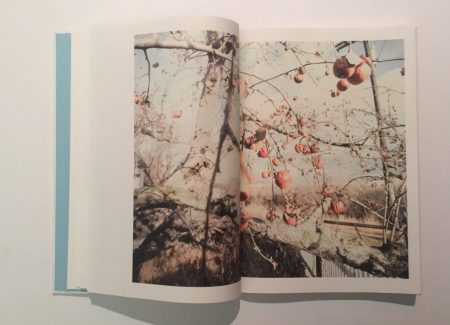

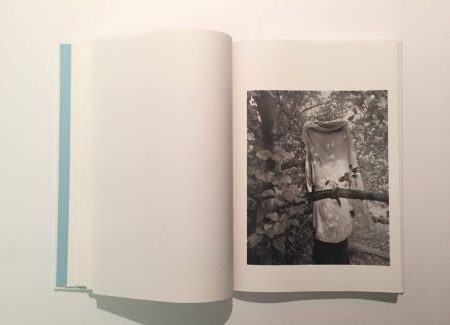

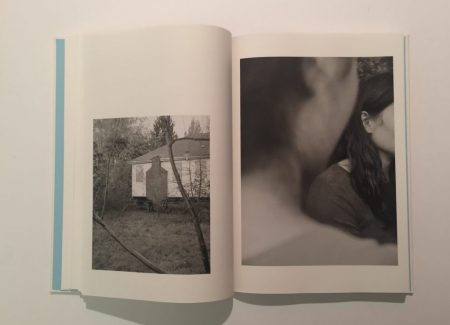

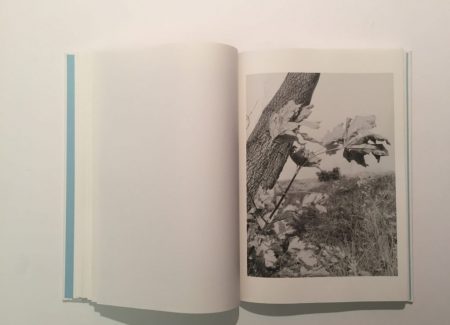

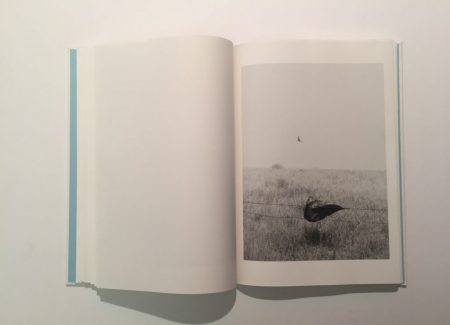

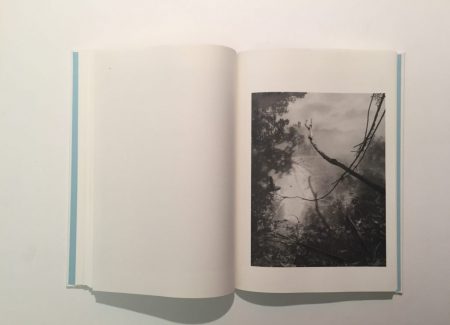

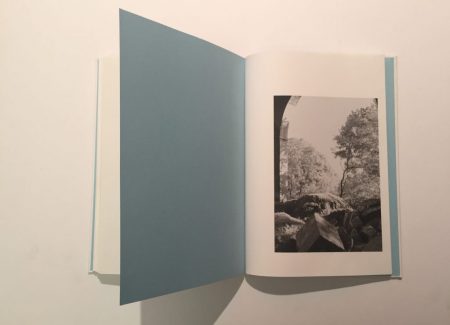

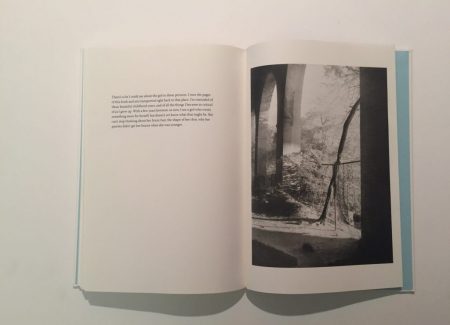

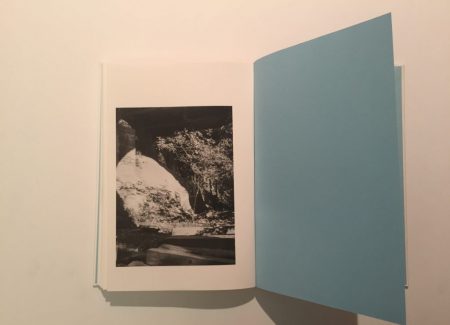

A similar longing is also palpable in Meeks’s domestic landscapes, which are interspersed throughout the book and define it just as much. We see houses resting on wooden platforms, thickets and railroad tracks, branches that look like wires and vice versa – all of which were taken in neighborhoods of former and current homes, including Missoula (Montana), Portland (Oregon), and upstate New York. There is a tangible weight, almost melancholy, to these pictures that unfurls in nuanced tonalities – in what is captured and how – and is difficult to describe, because there is neither nostalgia nor commemoration, but a feeling closer to memories dissolving from the edges. A sensation that not even the four color photographs of daisies, a clearing, and an apple tree, which punctuate this book, can fully alleviate. What surprises about these photographs is that, despite their different provenance, they create the succinct feeling of a single place: one shaped by open skies and murky ponds, where a plastic bag billowing in the wind is regarded with the same attention as the bird flying above, where the promise of summer is evoked by frozen apples dangling from a leafless tree. A place, where nothing happens, prone to be moved away from, haunting nonetheless.

In this regard, and in many others, Somersault continues to explore the themes of home and domestic living – of “how we inhabit and break away from places, and how these places continue to inhabit us” Meeks says – as he has done in previous publications, such as cyprian honey cathedral. Somersault, however, is also distinctly different. Partly, because it revisits and reinterprets the visual archive of a former project, which culminated in the hand-made book pretty girls wander, self-published by Meeks in 2011. Partly, and perhaps more importantly, because this reinterpretation allowed for a new collaboration between Meeks, his daughter, and his son Adam.

As a photographer, Meeks finds it inherently difficult, both emotionally and artistically, to return to a body of work once it is completed. “I feel like my vision continues to evolve rapidly,” he recently told me, “so I often tire of my pictures in the months after I make them. My motivation for making this book was different, because instead of merely producing a trade-edition of the same book, I wanted to bring the three of us together again – and to see how we have changed.”

The change manifests in the sequence and selection of images, made by Adam (who had also helped sequencing pretty girls wander), a new text by Meeks, as well as in the inclusion of a new small chapter at the book’s end – the coda, where three sunbathed landscapes accompany a text written by Abbey. The result is moving, for it extends the layers of time and introspection into a commonality of experience looked at from different angles. And while the pictures’ edit and sequence still seem to follow the pulse and pause of those late-teenage years, where things either slip away or twinge with a threat of un-eventfulness, it is the words that illuminate the shape-shifting relationship with ourselves, and the ones we love.

Within a tradition of American photography that has turned its eyes to the topographies of margins and the intimate, Somersault resides somewhere between the visual wonder of Minor White, Emmet Gowin’s muted tenderness, and the luminosity of Robert Adams. Lastly, though, Somersault is a book about a father’s sensibilities – about seeing the things and moments around him (and us) that go unnoticed and can’t be named. But it is an unlikely dialogue, too.

“Thank you for trusting me with these representations of your image,” Meeks concludes, addressing his daughter, “to weave a fiction that, we hope, points towards common and abiding truths.”

A few pages later, I read words that feel like a response: “When I look at this girl now, her insecurities are the least interesting thing about her,” Abbey writes. “She’s not unlike those trees and grasses. Swaying, existing, growing slowly. Knowing and not knowing. She wants to climb on a train and go where it takes her. I am very much still like her, somehow.”

Somewhere within the white space of those sentences hovers the leap of possibility, the seed for a continued encounter.

Collector’s POV: Raymond Meeks is represented by Casemore Kirkeby in San Francisco (here), Charles A. Hartman Fine Art in Portland (here), and Galerie Wouter van Leeuwen in Amsterdam (here). Meeks’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.

‘Somersault’ to me is a backwards flip in time to the previous iteration of this work, the limited edition artists book, ‘pretty girls wander’ october 2011. This ‘new’ work is a re-edited issue with additional photos.