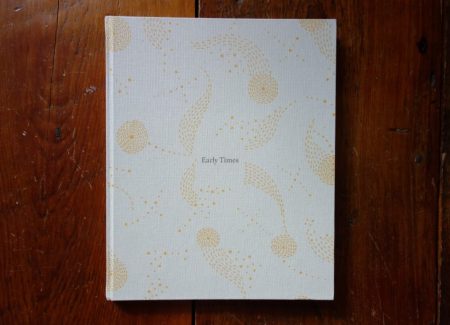

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2016 by Chose Commune (here). Hardcover, 104 pages, 48 color and black and white photographs, some with hand tinting. Includes a narrative text by Anjali Raghbeer and reproductions of vernacular ephemera. In an edition of 1600. (Cover and spread shots below.)

A website for the larger project, entitled A Myth of Two Souls, can be found here. A special edition of the photobook includes one of three inkjet prints and a linen clamshell box (here).

Comments/Context: The artistic activity of reinterpretation carries with it a set of unique challenges that are subtly different from blank slate original creation. When a foundation narrative or framework is already set, perhaps via an underlying allegory, fable, epic, or religious story that is often well-understood by the audience, the artist must innovate within a set of defined boundaries, rendering or restating rather than starting fresh. The task becomes an effort to follow (or not follow) the agreed-upon arc while simultaneously finding ways to give it new life, infusing the familiar and the allusive with the artist’s own viewpoint.

Across the long sweep of art history, retold stories have often been drawn from an oral tradition or a classic text, and much of the artistic reinterpretation has taken place in the domain of painting, with drawing, illustration, and manuscript illumination providing alternate pathways into a similar set of artistic outcomes. In each case, the action was one of visualization, of translating text into imagery and of highlighting pivotal moments in the narrative.

Given the relative youth of photography, when it has been used in artistic reinterpretation, it has often been involved in a second-level translation, where the photographs must not only deal with the implications of the original text, but also consider the context of images in other mediums that may also be informing the viewer’s conception of the story. Julia Margaret Cameron’s 19th century photographs inspired by Tennyson’s poems or scenes from Shakespeare provide an example of this thick multi-layered resonance, collapsing our own what-do-these-people-look-like visualizations, other well-known pictures/enactments of these same scenes, and the artist’s own richly romantic ideas.

Vasantha Yogananthan’s multi-year project to photographically reinterpret the Hindu epic of The Ramayana (originally recorded by Valmiki in roughly 300 BC) is an ambitious effort to artistically reconnect with a story that continues to percolate through everyday Indian life. This specific photobook, Early Times, is the first of what will ultimately be a seven-volume set of photobooks, captured under the larger title A Myth of Two Souls. And just as Cameron’s pictures brought a distinct sensibility to age old texts (in her case, the dreamy drama of the Victorian period), Yogananthan’s pictures enliven classic scenes from the lives of Rama and Sita with a dose of his own contemporary energy.

Early Times sets the Ramayana stage with an abbreviated story that both introduces the characters and covers the high points in the first part of the famous saga – King Dasharatha, soothsayers, his three wives, his daughter Shanta, the need for a male heir, various talking animals, Vishnu descending to Earth as Rama, the arrival of other sons, King Janaka, his daughter Sita and the destiny of daughters, the education of Rama, the seer Vishvamitra and his demand for Rama, and the journey to become a demon-fighting warrior. And while these details linger in the realm of legend, Yogananthan’s landscapes and staged portraits reroot the story in a sense of current day reality.

Image sequencing often plays an important role in the flow and feel of a photobook, and in this case, Yogananthan’s sequencing is quite literal – the images follow the progression of the story in lock step, with many of the pictures illustrating particular plot points or descriptive elements, using various locals as stand-ins for the main characters. And with the text and images shown in clusters, a sense of forward rhythm emerges – we alternately hear the story (in our heads) and see the accompanying pictures, the narrative repeating and building back on itself in waves.

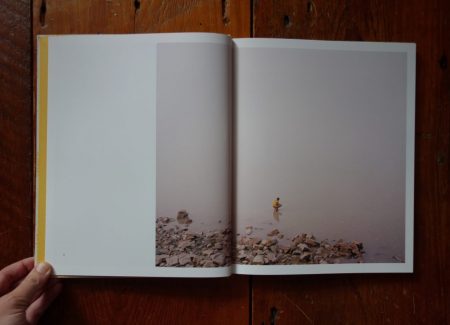

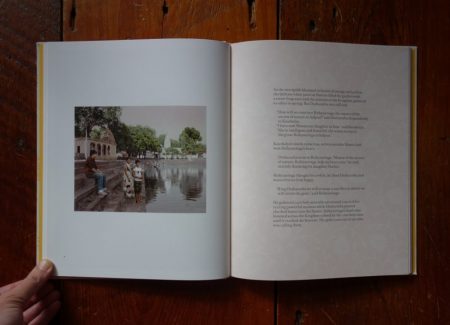

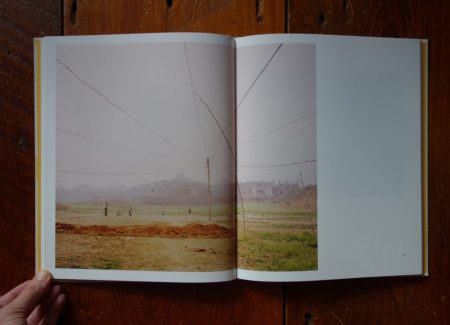

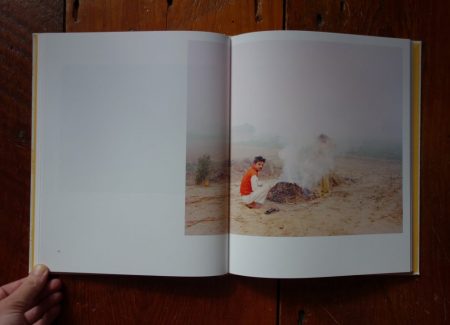

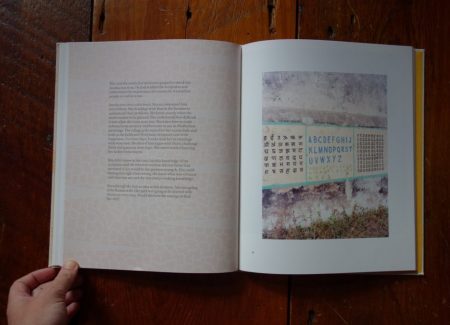

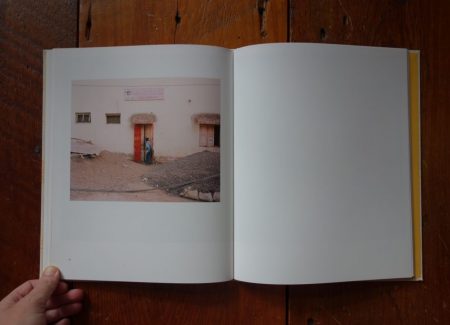

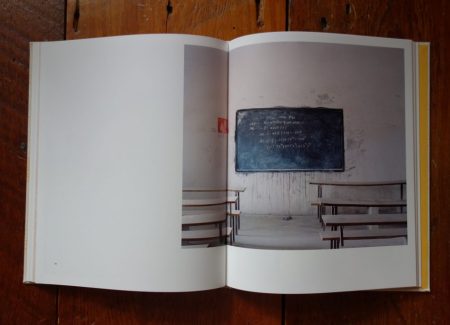

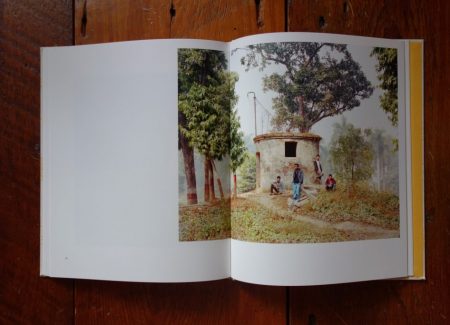

Photographically, Yogananthan has used a variety of approaches to construct his magical timelessness. Color landscapes set the scene and provide the backdrop for the narrative – many are shrouded in a soft mist, where wide river views, scrubby vacant lots, cauliflower fields, and cows, monkeys, and peacocks seem to float in mysterious uncertainty. Others document telling details that help fill in the gaps in the story – a flyer for an infertility clinic, a jaunty display of hair oil, a hand scrawled height chart, a blackboard with algebra equations, and some incense burning. Each one connects us back to the original tale (the wives having trouble bearing sons, Rama growing up and getting his education etc.), but with a pared down, modern twist.

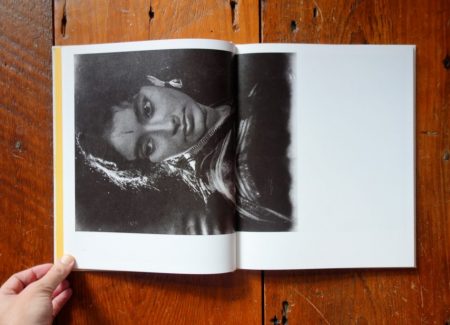

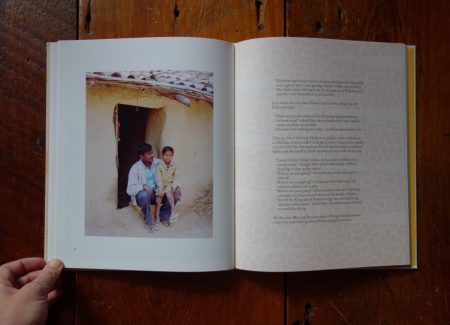

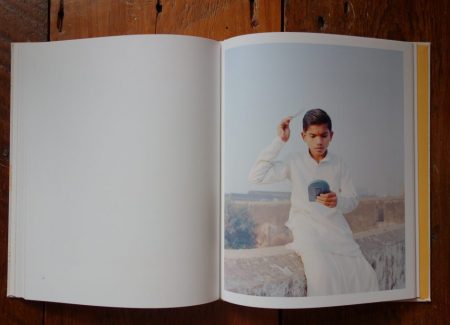

Many of the images with local people acting out scenes from the epic were taken in black and white and then hand colored or decorated, giving them just the slightest hint of heightened surreality – as viewers, we are already trying to quietly reconcile the historical story with the anachronisms of Mickey Mouse t-shirts, overhead electric wires, and muddy brick construction, and these sublty enhanced colors make those jolts more pronounced. These effects also tie back to the Indian tradition of manuscript illumination, paying tribute to one form of interpretation by honoring it in another.

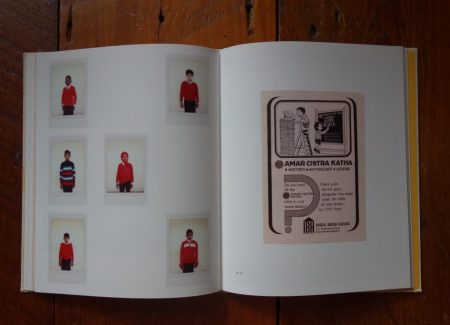

Still other techniques add further depth and complexity to the retelling. King Dasharatha’s three wives are captured in relative close up and in the shadowy expressiveness of moody black and white, bringing us inside their struggles. And local ephemera, from grids of schoolboy portraits to actual Ramayana texts bring us back to grounded tangible modernity. Seen together, the ancient Ramayana moves back and forth between the impressionistic and the specific, continually adapting to the changing circumstances.

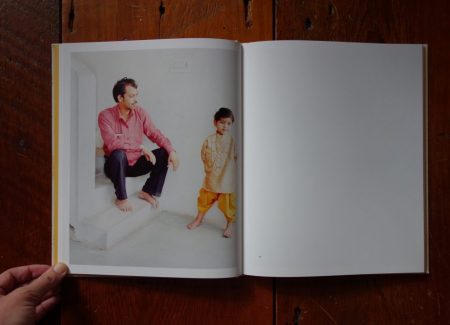

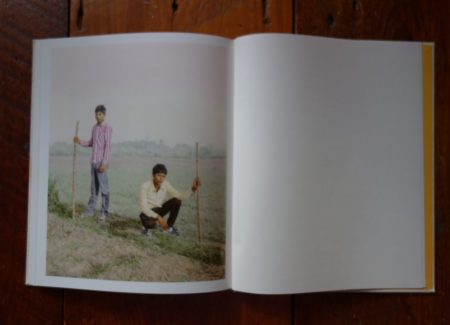

Some of the most memorable images in the book capture Rama in various stages of his early life (and played by different boys). His father appraises him (in both fondness and with some apprehension) in his regal attire, the young boy’s soft face aglow; a few pages later, he sits in his mother’s lap bathed in the pure light of the morning, innocent and somehow charmed. Further on, we see him heading into a humble school (flanked by a massive pile of grey stones), and then carefully combing his silky black hair with the attention of one who is recently aware of his appearance. By the end of this first volume, Rama becomes a lanky boy-to-man teenager, moving between moments of tenderness and awkward sullenness, wielding a bamboo pole as a weapon and hanging out with his brothers and classmates. And we have seen passing glimpses of Sita, but the story is just getting started.

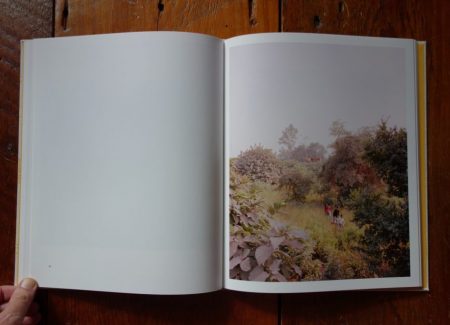

The riskiness of the intermingling of fact and fiction in this project is what gives it its memorable vitality. Yogananthan’s photographs deftly move between the fantastical and the mundane, and when the everyday views of an improvised cricket match, a boy bathing near a steel drum, or girls traipsing through the underbrush match up with the events of the epic, it’s like everything suddenly clicks, and we are transported somewhere special, collapsing the vast distance between past and present. This kind of integrated photographic storytelling isn’t seen very much these days, but Early Times reminds us of its elemental power. Knowing a few of the twists and turns coming up for Rama, it will be exciting to see how Yogananthan chooses to play out this story in the coming volumes. And if the subsequent books are as strong and nuanced as this one, the complete set will stand out as something durably enchanting.

Collector’s POV: Vasantha Yogananthan does not appear to have gallery representation at this time, so interested collectors should likely follow up directly via his website (linked in the sidebar).