JTF (just the facts): A total of 14 color photographs, framed in white and unmatted, and hung against beige-colored walls in the main gallery space, the smaller side gallery, and the entry area. All of the works are archival pigment prints, made in 2022 or 2023. The prints are sized roughly 30×23 (or the reverse), 40×30 (or the reverse), and 60×45 (or the reverse) inches, and all of the prints are available in editions of 10+2AP. (Installation and detail shots below.)

Comments/Context: Artistic inspiration is an elusively opaque and serendipitous force, where fresh new ideas and unexpected lines of thinking can potentially come from almost anywhere. One hunting ground artists have consistently scoured for inspiration has been the work of other artists across the ages, where one artist’s hard earned solutions to thorny problems of subject matter, approach, technique, process, tone, style, or other choices can be liberally borrowed from or adapted to another artist’s particular pressing needs. In some cases, the homages and respectful reuse from one artist to another can be quite deliberate and visible, making the links, connections, and echoes overt, while in others, the influences may have been internalized so thoroughly by the receiving artist that we might never be able to detect where the spark of inspiration originated.

In his newest photographs, Abelardo Morell has taken as his influence the works of Claude Monet and Vincent Van Gogh, two 19th century painters who could hardly be more well known and obvious. The broad, easy familiarity of their work immediately raises some tougher questions, at least in terms of influence. How might Morell embrace some of their ideas (many of which were altogether radical for their times) without seeming saccharinely and preciously derivative now?

One area of interest that has run through Morell’s long career in photography has been a continued exploration of the possibilities of the camera obscura. While the relatively straightforward pinhole projection technology has been well understood since ancient times, Morell first gained prominence in the late 1990s with black-and-white camera obscura images he made in hotel rooms and empty apartments in places like New York, where urban scenes and notable landmarks were projected across the walls, ceilings, and other surfaces of these anonymous rooms. In the succeeding years, he has gone on to further refine his process, finding ways to reverse the natural image inversion that takes place, working in rich color, and traveling to various places around the world to bring other famous landmarks, tourist sites, and ornate underlying rooms into his frames.

One challenge Morell encountered along this artistic road was how to make a camera obscura landscape image out in nature, without the use of a handy darkened room (or cave); there are generally no hotels to visit out in the midst of the rugged American West, especially in the open wilderness areas documented by so many notable 19th century photographers. So roughly a decade ago, Morell invented a portable technical solution that didn’t require a room, which he called a “tent-camera”. They key innovation in this device is the use of a 90-degree prism which projects the camera obscura image down onto the ground instead of onto a non-existent nearby wall; with the aid of camera mounted on a central tripod and a surround of dark wrapping material, Morell is able to make images that combine the view of the landscape with the texture of the ground underneath his feet. With this relatively portable device, Morell went on to make images in many of America’s national parks, mixing mountain vistas with various elements of dirt, rock, grass, pine needles, sand, and other surfaces, each adding its own tactile aesthetics and mark-making possibilities to the images cast upon them.

Since both Monet and Van Gogh often worked outdoors (in the plein air), Morell’s tent-camera allowed him to photograph at many of the same places these two visited, including Monet’s garden at Giverny and many of the spots Van Gogh walked, near Arles, Vétheuil, Auvers, St. Remy de Provence, and other towns and villages in the south of France. In this way, Morell could photographically explore essentially the same terrain and subject matter – the gardens and ponds, and the wider vistas of fields and cypresses in the spring and summer – making images that recall the compositions of the two painters. He could also experiment with an analogue to their expressive brushwork – the tent-camera grafts the camera-obscura views onto the textures on the ground, creating the potential for hybrid surfaces that could mimic (or at least recall) Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paint application.

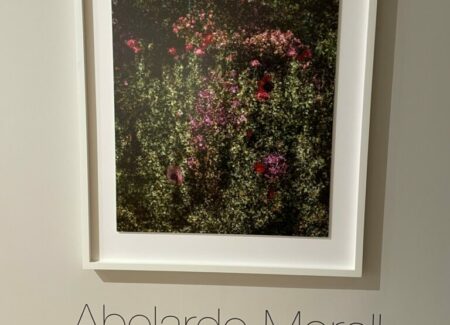

At Monet’s gardens in Giverny, most of the pathways are made from mixed stones of rocky gravel, so when Morell’s tent-camera images are cast on top of them, they create shifting dappled surfaces just like Monet’s brushwork. Morell shows us views of a majestic yew tree and its shadows, lily pads in the ponds, riverside views filled with overhanging limbs and lush greenery, and various garden and floral scenes where the paths underfoot are covered in fallen petals and blossoms, adding further decorative possibilities to the combined compositions.

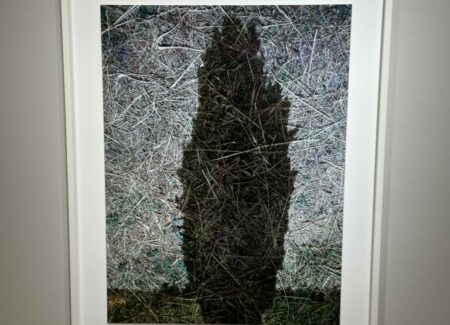

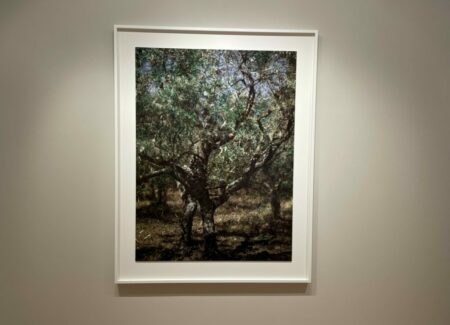

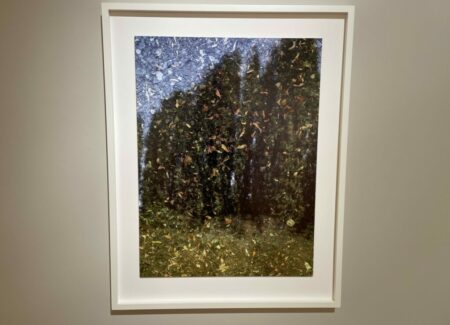

When he channels Van Gogh, Morell heads out into the fields, where red poppies, yellow sunflowers, and spiky cypresses provide landscape interest. The ground underneath his tent-camera is much more varied on these walks and rambles, and he is consistently able to creatively match these textural changes to the surroundings. Cypress trees are paired with the lines of fallen needles in one image, creating insistent marks that flow through the work like Van Gogh’s long brushstrokes, while another cypress composition uses a rocky pathway with small round stones as a proxy for “The Starry Night” and its sparkling round stars. Morell’s images of the wider fields are generally placed atop hard dirt paths or dry zones, while a portrait of a gnarled olive tree uses the fallen leaves and weedy grasses nearby to help accent the shimmery movement of its leaves.

In the end, Morell successfully finds his way out of the stifling trap of inspiration, using his own ideas and innovations to insert his unique artistic voice into these familiar scenes and subjects. Conceptually, he has done something unexpected – he’s found a new way to bring textural richness and sumptuous uncertainty to the surface of an unmanipulated photograph, one that isn’t simply a sandwich of unrelated negatives but is instead rooted in a specific place and an immediate experience. That’s a durably powerful idea, and one that Morell can now leverage in countless other risk-taking directions.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced at $18000, $26000, or $38000, based on size. Morell’s work has become consistently available in the secondary markets in recent years, with prices at auction ranging between roughly $2000 and $30000.