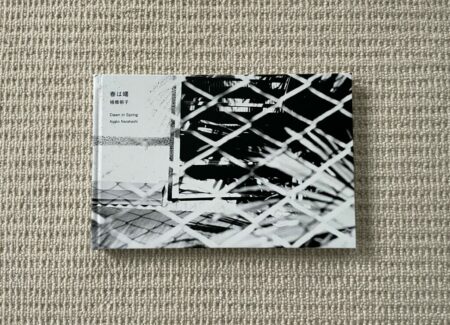

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2023 by Osiris (no book link on publisher site, available here). Hardcover, 173×257 mm, 120 pages, with 79 black-and-white reproductions. Includes a short statement by the artist (in Japanese/English), as well as a set of thumbnails (Japanese captions only). (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Unearthing a well known photographer’s early work almost always offers some tantalizing possibilities for discovery. Does the work show the aesthetic beginnings of the artist’s more evolved later style? Are there other influences or interests present? Are the pictures interesting at all, or just the experiments of an inexperienced photographer learning his or her craft? Looking backward, we instinctively want to connect the artistic dots into a logical progression that aligns with what we know actually happened, and so perhaps we often see what we want to see. It’s like already knowing where the pathway eventually led and walking back, hoping to find the bread crumbs that began the journey.

Dawn in Spring gathers together images made in 1989 by the Japanese photographer Asako Narahashi. At that time, Narahashi had just graduated from Waseda University, and decided to travel around Japan, and the pictures included in the photobook jump from Tokyo to various locations around the country. It wasn’t until the early 2000s that Narahashi dedicated herself to the landscapes seen from the water that would become her signature, taking shape as her now instantly recognizable 2007 project Half Awake Half Asleep in the Water, and its successor some years later Ever After (from 2013, reviewed here). But back in 1989, she was an early career photographer still very much finding her footing, and Dawn in Spring chronicles that initial scavenging search for a more durable artistic direction.

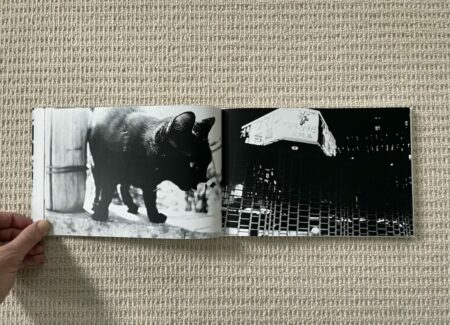

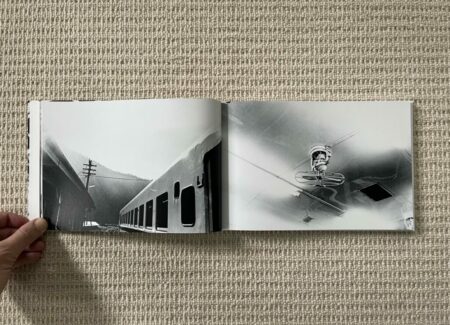

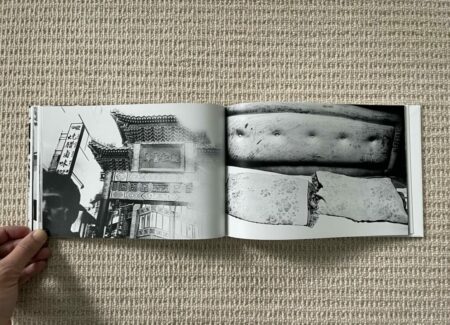

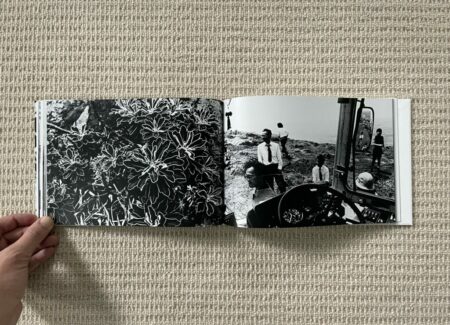

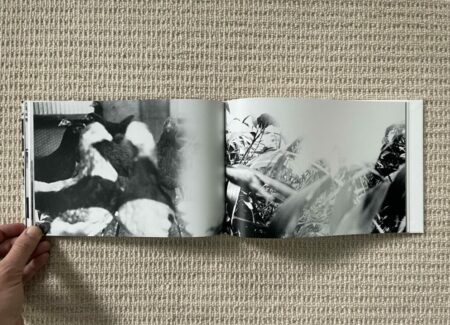

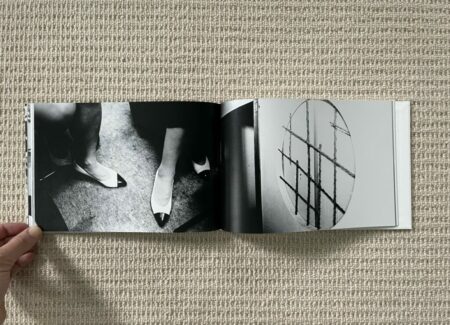

Narahashi had attended Daido Moriyama’s “FotoSession” workshops while she was in school in the mid-80s, and many of her early photographs recall the dark moody atmosphere of his pictures, and those of his other Provoke contemporaries. She liberally explores and adopts tunneled darkness, high contrast, thick mid-tone greys, enveloping blur, and bristling flares of light, applying these aesthetic lessons and techniques to whatever she was seeing in her travels. Images of a store window mannequin behind a sweep of visual interruption, two pairs of shiny black-and white women’s shoes, a grimly headboard inscribed with names and messages (perhaps from a love hotel), a painted billboard filled with the smiling open-mouthed face of a woman, some white edged black plants, and various black kittens seen from low angles might reasonably be mistaken for pictures made by Moriyama.

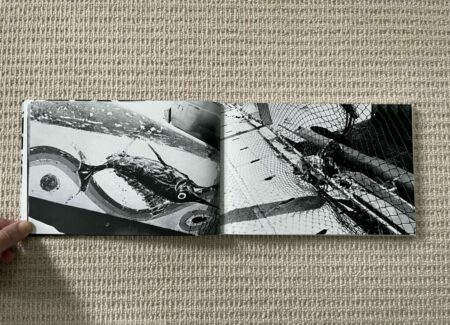

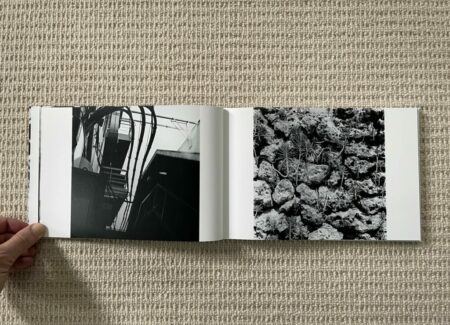

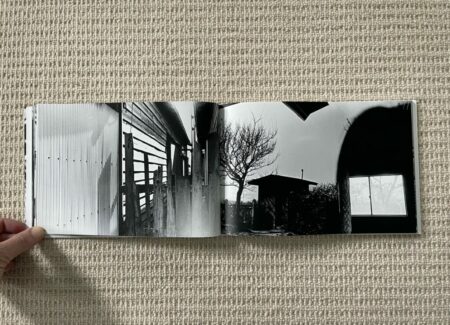

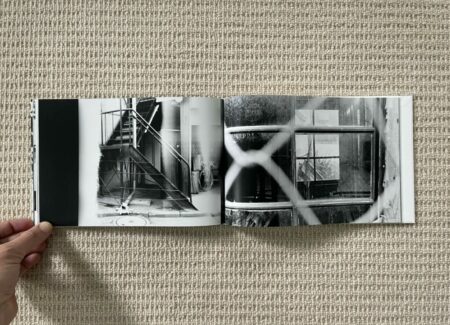

More intriguing are Narahashi’s seemingly deliberate efforts to teach herself to see photographically, where she alternately plays with high and low camera angles, sees through different kinds of veiling and interruption, and gets unnaturally up close or steps back to take in broader views. She looks down at trash caught under a chain link fence, up at a trio of overhead wires snaking between buildings, up again from underneath at a fan mounted on the ceiling, down the stairs on a ferry, and up from the ground through a tangle of weeds, each composition thrown off kilter just enough to turn the ordinary into something unexpected.

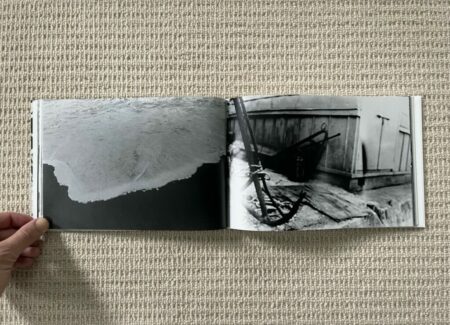

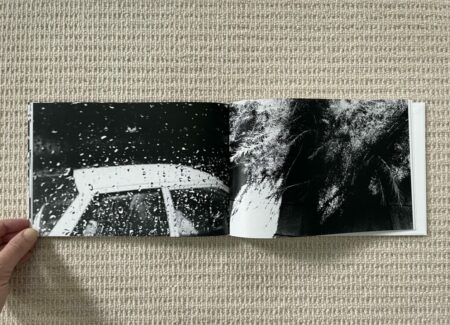

Several other images feature windows as an organizing device, with gridded security panes, curtains, and dirt providing added layers of geometry or texture. Narahashi also finds use for a mirror (for a darkened self-portrait flanked by a painted face), various train windows (with landscapes turned into softened horizontals by the motion), and chain link fence (to introduce diagonal patterns to otherwise squared off or telescoped views of window frames and staircases). One view from inside a bus is particularly complex, with passengers standing around outside captured in various windows and the side mirror. Still other pictures use dappled tree shadows as a veiling device, peer through windows covered in splotchy paint, and look more closely at glass surfaces covered with water droplets and sloshy residues. It’s clear from all these experiments that Narahashi was actively trying to develop alternate modes of seeing, reorienting her vantage point by consciously avoiding straight vision.

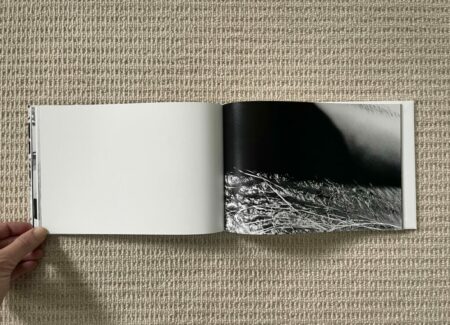

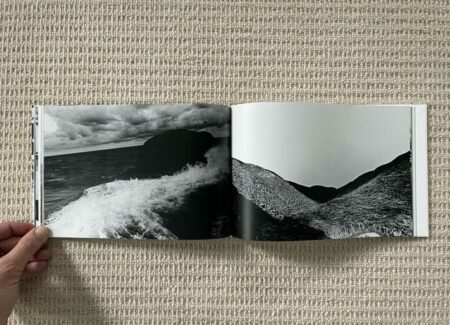

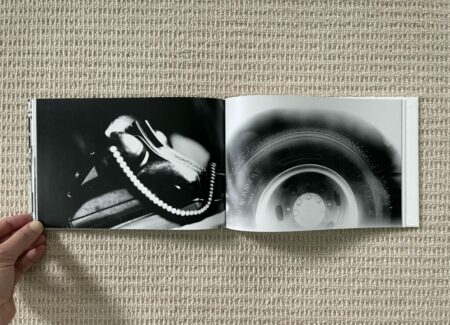

Disorienting close ups are another strategy she employed for extending her perspective. She looks closely at what looks like a shirt hung over a chair, a truck tire, a telephone (whose cord becomes a seductive line of flared dots), some chickens, and a cow’s eye, each object transformed into a formal (or pattern) study. Two images of draped items (one of negative strips, the other of hanging laundry and a light bulb) create a similar sense of momentary confusion, as we try to puzzle out what we are seeing. Close up images of waves, froth, and water are also a repeated interest, the compositions often cropped down into studies of elemental light and dark, and when Narahashi pulls back to take in a wider view, foreground and background tussle, with waves or grasses set against undulating layers of sky, land, and ocean. If this sounds familiar, it should, as Narahashi would go on in the coming decades to look at the land from essentially underneath the waves, creating a suffocating, almost drowning feel of cities and mountains being overcome by the water; these examples clearly predate those more famous efforts, but feel intellectually connected by related compositional problems and potential solutions.

The design and construction of Dawn in Spring match well with an early body of work – the photobook is straightforward, small, unfussy, and largely unadorned. Most of Narahashi’s early pictures are landscape format, so these dominate the full bleed spreads; the few vertically oriented pictures are turned sideways to fit into the wide book setup (which pleasingly makes them even more confusing), and another few square format images are given white side borders so they can be placed on the wide pages. The only other notable design detail is that the thumbnails and text pages at the end of Dawn in Spring are printed on slightly thinner and glossier paper, subtly setting them apart from the main pages of photographs.

As seen here, Narahashi’s early work is far stronger than we might have expected. This isn’t just a nostalgic, “where it all began” trip down memory lane – these are consistently thoughtful and challenging black-and-white photographs, with plenty of experimentation and risk taking going on. For ostensibly a group of travel photos taken after college, they stand up well to both the passing of time and the intense and sophisticated gaze of an artist looking back on her own aesthetic roots.

Collector’s POV: Asako Narahashi is represented by ROSEGALLERY in Santa Monica (here), Pirska Pasquer Gallery in Cologne/Paris (here), PGI Gallery in Tokyo (here), and Ibasho Gallery in Antwerp (here). Her work has little consistent secondary market history, so gallery retail likely remains the best option form those collectors interested in following up.