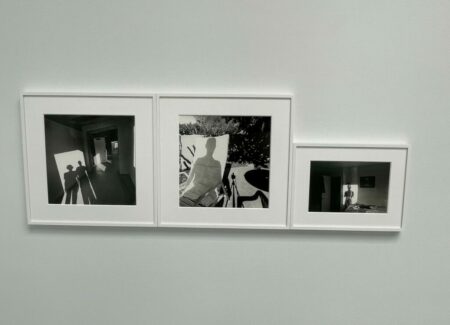

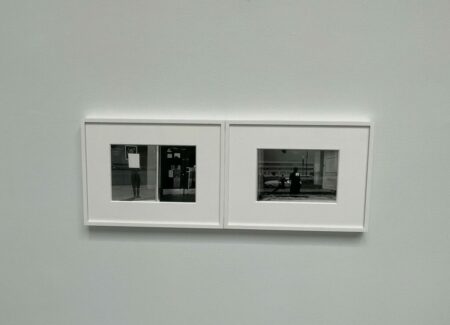

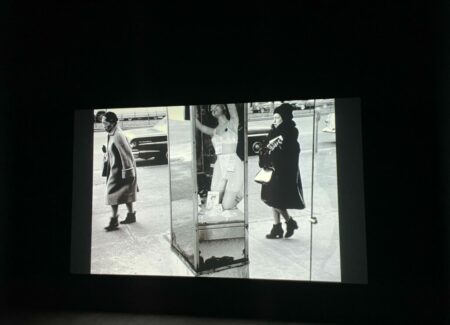

JTF (just the facts): A total of 51 black-and-white photographs, framed in white and matted, and hung against white walls in the main gallery space and the entry area. All of the works are gelatin silver prints, made between 1962 and 2007, in a mix of vintage and modern prints. Physical sizes range from roughly 6×9 to 12×18 inches (or the reverse), and the prints are uneditioned. The show is accompanied by a video projection (of Friedlander’s images) by Joel Coen, 3 minutes 43 seconds. (Installation shots below.)

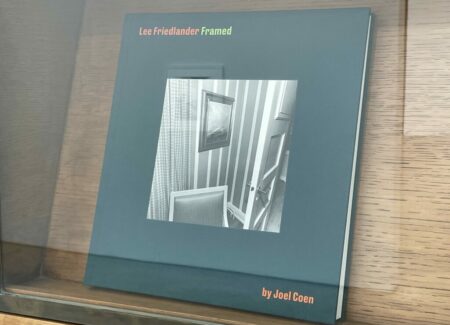

A concurrent exhibition is on view at Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco (here), and a monograph of this selection of images has been published by Fraenkel Gallery (here). (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: When a photographer is as astonishingly prolific as Lee Friedlander, the challenge is never to find enough worthy pictures to look at or to celebrate. In fact, the very real problem is to somehow cut his seven decades of uniquely masterful output down into something we can visually comprehend and digest in one visit to a gallery or in one flip of a photobook. And so, for the most part, aside from a few sprawling museum retrospectives over the years, Friedlander’s abundant production has generally been narrowed to more manageable subject matter themes or discrete projects. The list of such edits is wonderfully wide ranging and eclectic: views from car windows, TV screens, nudes, desert landscapes, shadowed self-portraits, monuments, floral stems, chain link fencing, shop window mannequins, portraits of his wife Maria, apple trees, mountain scenes, city parks, jazz musicians, factory workers, fashion shows, and vernacular signs (just to name a few), and even when we do this, there are still more potential categories and motifs to apply to Friedlander’s voluminous archive than we can ever really possibly hope to explore in full.

An alternate approach to what we might playfully call the “Friedlander problem” is to have the art world curators, gallery owners, and scholars (as well as the artist himself) step away from table and let someone else take a crack at finding a new (and maybe even unique or unexpected) entry point into the material. At its worst, this “celebrity curator” idea turns into a thinly veiled (and often painfully dull) exercise in self promotion or crass salesmanship, where the famous person chooses some favorites and we accept their selections simply because the chooser is a celebrity. But at its best, particularly when the celebrity is an artist of some kind him or herself (and therefore with a professionally-honed aesthetic point of view of his or her own), something much more interesting can take place – one artist re-interpreting the other, like a musical collaboration or a remix.

This show matches Friedlander with Joel Coen, the Academy Award-winning director of No Country for Old Men, Fargo, The Big Lebowski, and other memorable films. Given the dark, offbeat perspective found in many of Coen’s movies, it seems plausible and even likely that he would have an affinity for Friedlander’s eye, so conceptually the pairing seems apt. And as it turns out, there was more than just a superficial meeting-of-quirky-minds connection that took place between the two artists.

Of course, film making and photography are decently adjacent and complementary, at least in terms of artistic thinking. As a director, Coen inherently wrestles with how to build moods and stories out of cinematic sequences of imagery, and as a photographer, Friedlander faces similar construction tasks within the constraints of a single static composition. As a result, Coen seems to have intuitively understood and appreciated what Friedlander was doing with his innovative and often unconventional approaches to photographic framing, which then seems to have triggered a predictable impulse (at least for a film director) to build Friedlander’s photographs into sequences that reflect the patterns, repetitions, and resonances he saw in the pictures. In a sense, you could say that in this exhibit Coen has both figuratively and literally (since there is a Coen-directed slide show included in the presentation) built a non-narrative movie out of the visual raw material found in Friedlander’s photographs.

I can’t remember ever describing a gallery show of photographs as episodic, but in Coen’s hands, Friedlander’s images have been arranged into small self-contained episodes of two to four pictures, that have then been linked together into a larger flow that circles the gallery space with a sense of rhythmic progression. After a stage setting single image in the foyer (featuring a strangely dramatic Friedlander-ian concoction of a white van, an interrupting stop sign pole, and an airplane in the sky that looks like it might crash), Coen’s exposition beings with a simple pairing, both pictures built around doubled vertical lines, one from the 1970s on the George Washington Bridge and the other some thirty years later in Texas. They’re a smart starting point as they are both studies in clever compositional control, the two lines alternately flanking a railing post and a thin evergreen tree, narrowing our vision to the space between the two lines.

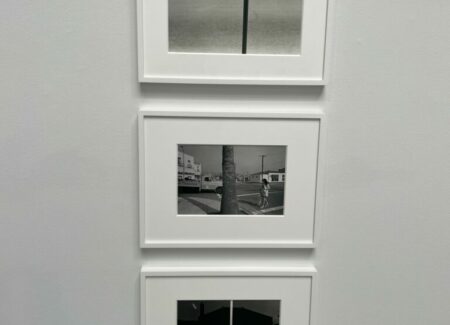

The next several images then visually explain how such found vertical lines (and similar objects) are used often by Friedlander to intentionally disrupt his compositions. A stone statue, a fire alarm box, a truck side mirror, a raised foot, a steel girder, and the wooden stick of an American flag are progressively found playfully getting in the way of whatever we might usually assume to be the primary subject of a photograph, often a person’s face or body. Coen then offers a triplet of single vertical interruptions right in the middle of the frame, where a sign post, a palm tree trunk, and a window frame (each near to random passersby) divide the pictures with crisply against-the-conventions precision.

Coen’s selections don’t follow an ordered chronological timeline, nor do they adhere to specific subject matter themes or motifs; instead they revel in the way Friedlander sees. After a well known image featuring the layered planes of various figures and a revolving glass door, Coen notices arrows pointing in different directions, more bisecting poles that split compositions in two, and a series of picture-within-a-picture framings that play with windows and rectangular cutouts. He then returns to more vertical poles that create optical illusions, are doubled by shadows, hold up chain link fences, and generally interrupt the visual proceedings with wit and formal elegance. Skew angled street signs provide a further opportunity for fun, which Friedlander uses to align with a pyramid, echo various street lights, cut through some dumpsters, and arrow straight into the sidewalk.

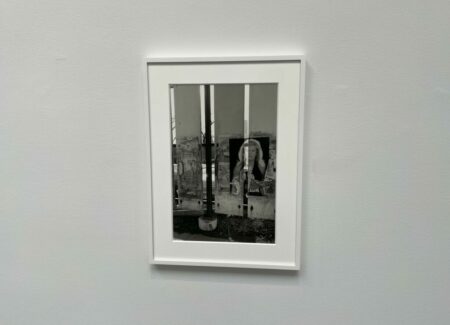

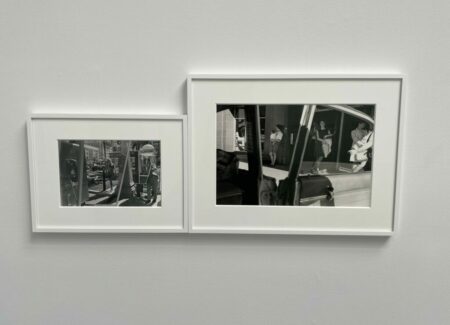

As the show continues, Coen’s interest in Friedlander’s compositional interruptions meanders further and ultimately builds to a kind of crescendo in the form of a pair of works, one from California in 1970 and another from Seattle in 1967, which are hung tightly edge to edge. Both are divided into three discrete sections (almost like film strips), with separate stories of various individuals framed by the poles and window edges. And both are marvels of ingenuity, as few photographers other than Friedlander would ever think to construct these kinds of densely organized arrangements out of found realities.

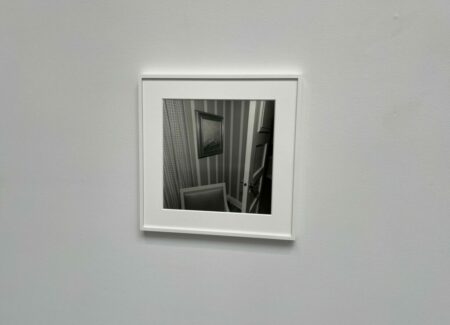

After this peak, Coen’s interest shifts slightly, looking more closely at how Friedlander has used windows and reflections, the progression working through various ideas, adding in mirrors and television screens to the inside/outside push and pull. The TV screens then transition to another round of empty frames and cutouts that serve to create pictures within pictures (including a particularly wry landscape framed through chain link fence and a wire frame creating a portrait of a parking space). The show ends with a selection of Friedlander shadows, his own shadow cast across various surfaces (including his wife), and the compositional idea then reversed by white boxes of light, which he uses to interrupt reflected self-portraits in shop windows. The last picture in the sequence finally places the light on Friedlander himself, the angled box of light cast across his face in Tokyo, almost like the bright light of a movie whose last film reel has spun away.

For someone outside the world of photography, Coen has done a satisfying job of both teasing out what’s durably important about Friedlander’s art and presenting it with a flair we haven’t seen before. He seems to have intuitively understood Friedlander’s sense of visual humor, and then dug deeper to unpack how Friedlander’s compositional approaches create formal opportunities for wrong-footing the viewer. Coen’s sequences amplify these observations and learnings, highlighting patterns in Friedlander’s organized but idiosyncratic seeing. Given the obvious synergy of their two artistic mindsets, perhaps Coen’s next film will incorporate a few Friedlander-esque interruptions and visual games, bringing the dialogue full circle.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced between $9500 and $21000 each. Friedlander’s work is routinely available in the secondary markets, with recent prices at auction ranging from roughly $2000 on the low end to as much as $80000 for his most iconic vintage prints. In 2015, a selection of Friedlander’s little screens (38 prints in all) sold for $850000.