JTF (just the facts): A total of 22 color photographs, generally framed in light wood and unmatted (aside from two of the smallest, earliest prints which are matted), and hung against white walls in a series of gallery spaces on both the main level and the downstairs area of the gallery. The exhibit was curated by the architect Toshiko Mori.

The show includes the following:

Front Gallery

- 2 c-prints, 1992, 1999, sized roughly 18×25, 34×34 inches, in editions of 6+3AP

- 3 c-prints, 2016, 2021, sized roughly 71×78, 71×88, 71×99 inches, in editions of 6+3AP

Hallway

- 1 c-print, 2017, sized 71×78 inches, in an edition of 6+3AP

Main Gallery

- 10 c-prints, 2006, 2010, 2014, 2015, sized roughly 71×58, 71×76, 71×79, 71×80, 71×87, 71×88, 71×89, 71×91 inches, in editions of 6+3AP

Downstairs Gallery

- 6 c-prints, 2007, 2011, 2014, 2015, sized roughly 71×76, 71×79, 71×83, 71×88, 71×95 inches, in editions of 6+3AP

(Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: For much of her photographic career, Candida Höfer’s work has been presented within the framework of organized categories. Some of her monographs have gathered together images of like places (such as libraries, churches, or zoos), asking us to see any one example in the context of the wider category, and offering us the pleasures of typological comparison. And in most of her gallery shows, going back a decade or more, Höfer’s work has been organized by geography, showing us spaces in Mexico (in 2019, reviewed here), Düsseldorf (in 2015, reviewed here), Rome, Florence, Naples, and Philadelphia, just to name a few, encouraging us to see how environment (and history) might be visible in local architecture, and once again making us think about how a library or church in one place differs (or doesn’t) from another found half way around the globe.

This exhibit, curated by the Japanese architect Toshiko Mori, breaks that categorical mold, and instead provides a straightforward survey of Höfer’s work, albeit through the eyes of an architect. This vantage point is refreshing, as it subtly reorients our perspective on Höfer’s photographs – Mori doesn’t see Höfer’s images as pictures of places, things, or architecture more generally, but instead as pictures of experiences, in her words, “as if the architectural experience itself is an object to marvel at.” This line of thinking does something mind bending, in that as we now stand in the gallery spaces, we watch Höfer experience (and subsequently frame her own version of) the various places she visits, while we in turn experience her photographs in the particular architectural context of the gallery.

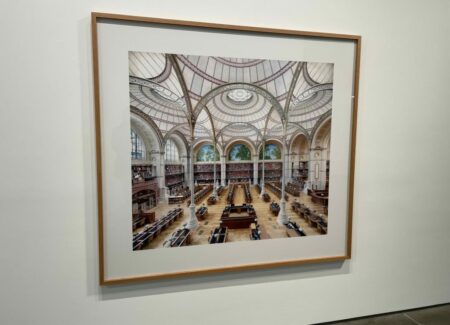

Rarely have I noticed the subtle relationships between photographs and their specific installation as much as in this show. In the entry hallway, a single image by Höfer provides a kind of introduction. It’s an image of a large reading room at INFA in Paris, and in the relatively narrow space of the transitional hallway, its elevated view out over the vaulted airy space feels unexpectedly open and expansive, amplifying the experience of looking out on the desks and stacks, like peering through a window.

Moving into the main gallery, the installation pulls our eyes all the way down to the far wall, where a rigorous interior view of an archive in Sevilla is symmetrically aligned along the spine of two intersecting rooms. It’s a sober study in black and white, meticulously ordered with black and white floor tiles, arched windows, and wooden cases, with lines and angles that split with precision; as seen from a distance, the space of the room seems purposely designed to lead us to this picture and its own layers of strict internal order. To the right of this image, in the right corner of the gallery, is a picture of the right corner of an intimate library in Lisbon, and this is where we really start to feel the architectural echoes that have been arranged for us in this show. The lines of walls and roofs create a doubled effect, even when we are drawn in by the piano, globe, and floor-to-ceiling bookshelves in Höfer’s carefully structured image.

All of the works along the left wall of the main gallery are flattened views of spaces, with increasing visual depth as we move from left to right. The first work, again from the Archivo General de Indias in Sevilla is the most frontal, with the geometries of its arches, stacks, and floor tiling made even more prominent by the flattening eye of Höfer’s camera. Successive images look deeper into ornate libraries, where shelves are surrounded by marble columns and cornices; as we continue, the spaces become double height, with painted ceiling frescoes and even more majestic decoration, but the views are still generally squared off and centered, creating a calming sense of balance.

The arrangement of images along the right hand wall seems designed to create an in and out rhythm, beginning with a deep view down into an ornate library in Melk, followed immediately by a frontally flat view of a modern library in Mexico City, the contrasts of spatial dynamics (not to mention materials and general ambience) forcing us to reorient ourselves a bit. These are then followed by a vaulted central space with a glass ceiling and surrounding balconies (again in Mexico City, but in a different building) and a much tighter, low ceilinged library space in Santiago de Compostela, which aggressively pulls us down its receding lines of perspective. Seen as a linear progression, the four pictures create a kind of in-and-out motion, like a subtle pulsation.

The downstairs gallery at Sean Kelly is much more intimate, with a lower ceiling, and Mori has chosen a selection of Höfer’s works that have a central aisle or hallway (many of them churches or places of worship), which makes the smaller space feel deeper. Two ornate churches with wooden pews – one in Melk, the other in Schlierbach – fill one wall, while another church (all in white, in Düsseldorf) and another impressive hallway (in Altenburg) create a matched set on the other side. Höfer’s view of the Masonic Temple in Philadelphia is staged as the centerpiece in this room, with its unusual green columns and flanking seats giving it a more secular (if eccentric) feeling; a turn in the other direction offers Daniel Buren’s colorful intervention in Guadalajara, where half of the vaults and walls of the Hospicio Cabañas have been painted in primary colors, while the other half have been left bare, creating a boldly bisected view, which aligns with the view down the center of the Masonic Temple. In this way, the six pictures in this room are all aligned on the same grid or axis, amplifying Höfer’s own internal sense of order and alignment.

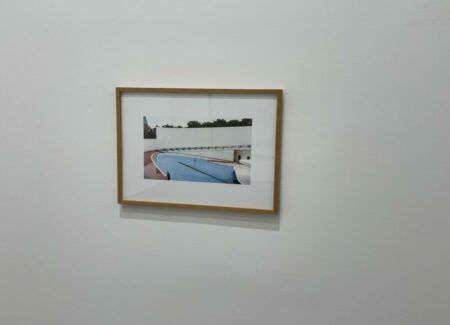

Upstairs in the front room, the architectural space once again controls our perception of Höfer’s photographs. The view from the doorway pulls our eyes across the room to a dizzying all white picture, looking upward through the spiraling turns of a staircase at the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein Vaduz. It’s a wonderfully subtle and disorienting photograph, which is initially difficult to decipher; Höfer has made spinning upward views of stairs before, but none is as geometrically enveloping as this one. When we finally turn away from its mesmerizing presence, two large images face off across from each other, one a particularly flattened view of a grey stone wall and doorway (at the same museum), the other a more undulating sea of circular patterns and mirrored reflections (at the Elbphilharmonie Hamburg). When these are finished tussling, two smaller niches invite us inward, to early views of zoos Höfer made in the 1990s, the one featuring penguins punctuated by interlaced architectural arcs that sweep around the swimming area.

The intentional nesting of architectural experiences in this show smartly activates Höfer’s photographs. It can be overly easy to sweep past Höfer’s scenes of grandeur, taking them in as conceptual specimens under glass; Mori’s approach asks us to think harder about the dynamics of looking at art in a specific space and about the subtleties of the aesthetic choices Höfer has made when documenting these architectural wonders. It’s an edit that energizes Höfer’s pictures, reminding us of the physical vitality that lies within these coolly organized views.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show range from €38000 to €66000, with some images already sold out. Höfer’s work is widely available in the secondary markets. Smaller pieces can be found well under $10000 (often in editions of up to 100), while the larger works (printed in much smaller editions, usually 6) have ranged between roughly $15000 and $125000.