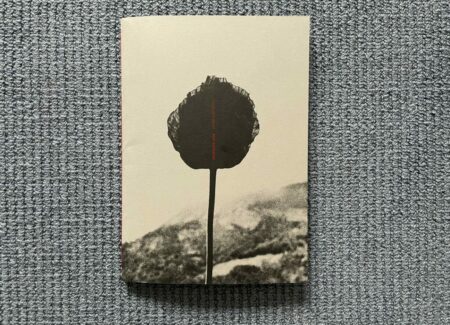

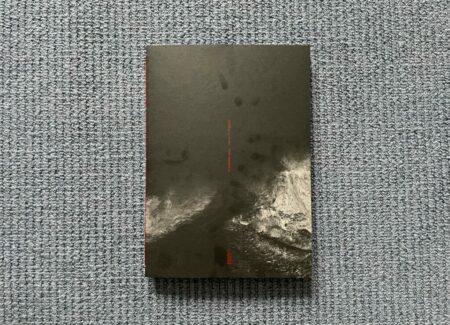

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2022 by KWY Ediciones (no book link, publisher site here, artist book link here). Multi-fold softcover with red string binding, with approximately 60 black-and-white photographs. Includes a foreword by the artist (in English/Spanish) and poems by Hubert Matiúwàa (in English/Spanish). Design by Vera Lucía Jiménez. (Cover and spread shots below.)

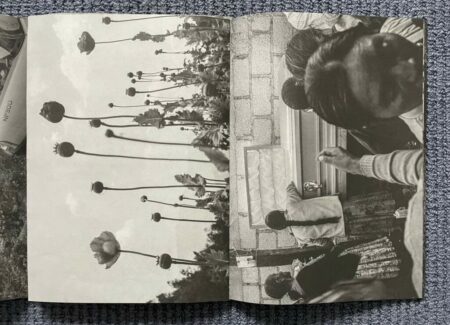

Comments/Context: The cover of César Rodríguez’ recent photobook Montaña Roja (or Red Mountain) features a single poppy stem and blossom silhouetted into a bold dark form, like the rising of a black sun. Printed on grey cardstock, with the artist’s name and the book title in small red type in line with the vertical stem, the image feels textural and grainy, almost ominous in its hovering presence.

Montaña Roja tells the story of the farmers living in mountainous region of Guerrero, in southern Mexico; Rodríguez has been visiting the area for the past 15 years, and his book gathers together scenes from everyday life, documenting both the people and their cultural traditions. The complex backdrop to the symbolic poppy on the book’s cover is a tangled tale of politics, economics, geography, and agriculture, one that goes back decades. It includes a mix of Indigenous communities, communists, and guerrillas; the precipitous economic decline of traditional crops like corn and coffee; and the now constant power struggle between the army, the drug cartels, and various other insurgent forces, leading to a charged climate of illicit agriculture, violence, and poverty. The resulting choices for the local farmers are supremely difficult – grow the illegal crop to have enough money to survive, fight the law enforcement attempts to eradicate the very crop they are relying on, live with the near constant state of conflict and violence inflicted by the drug traffickers (who essentially govern the region), or give up and go North.

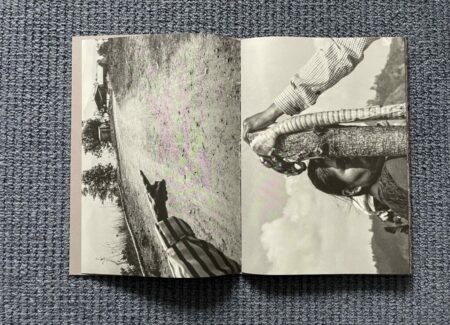

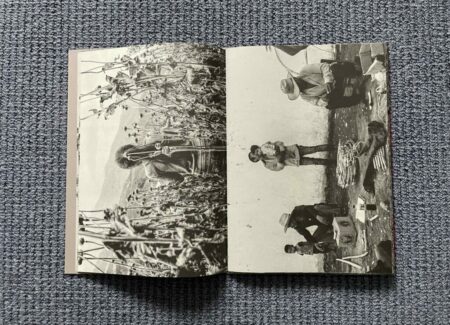

As grim as the situation sounds, Rodríguez’ black-and-white photographs try to dig into these abstract forces, by rooting themselves deeply in the lives of the people and the cycles and rituals of their days. And while there are resonant images of poppies growing, workers in the fields, and crops drying in the sun included in the book, Rodríguez largely turns his camera away from these activities and directs our attention to what’s happening offstage from the central contradiction of growing this particular crop. What he shows us instead is a community struggling to keep ahold of itself, where determination and perseverance take on subtle guises and compassion and hope search for ways to express themselves.

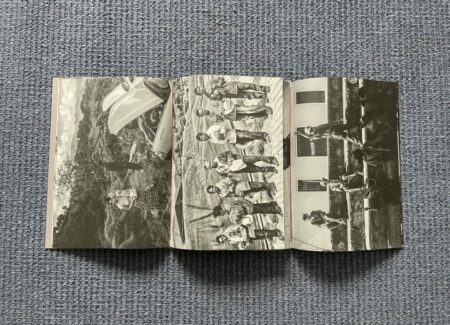

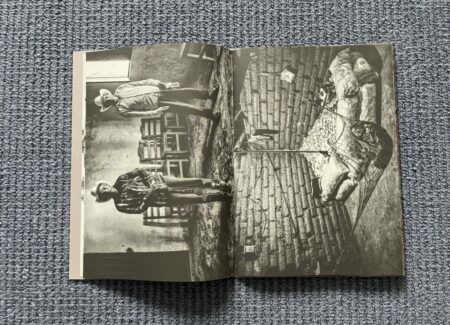

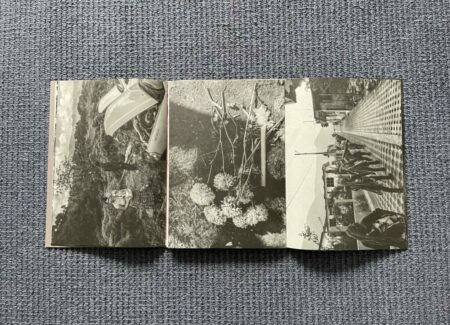

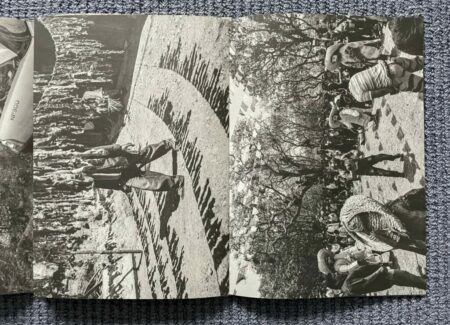

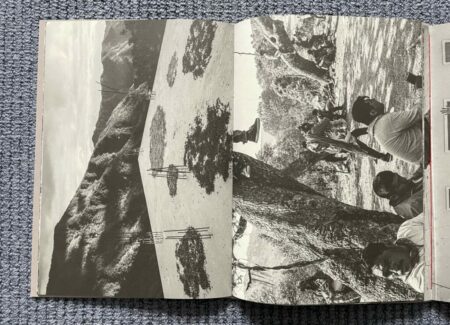

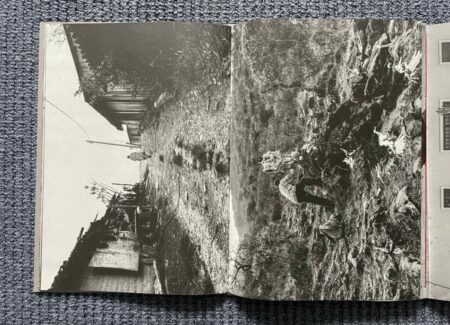

Almost before we get pulled into Rodríguez’ images, the innovative construction of Montaña Roja asserts itself. The cover opens to pictures that are horizontally oriented, but have been turned on their side to fit the vertically oriented design of the photobook, placing the binding at the top or bottom of the images. This twist of perspective is initially disorienting, but with a few pages flips, it becomes clear that it both makes us see the formal qualities of the photographs more closely and it adds a level of unease that matches the mood of the larger situation. The construction takes another turn a but further in, with the binding switching sides and the images folding inward in the opposite direction; we can now see that Montaña Roja is essentially interleaved back and forth, with a three part folded structure. When we eventually reach the end of the visual flow, there is one more twist awaiting us – yet another fold backward, which tucks underneath and holds a selection of poems, providing an elegant way to include the texts but keep them physically separate from the photographs. And the red stitching echoes the red color of the poppy flowers, tying everything together into one of the most cleverly unexpected and smartly appropriate photobook designs I’ve seen recently.

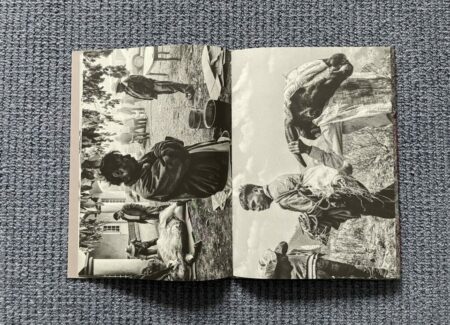

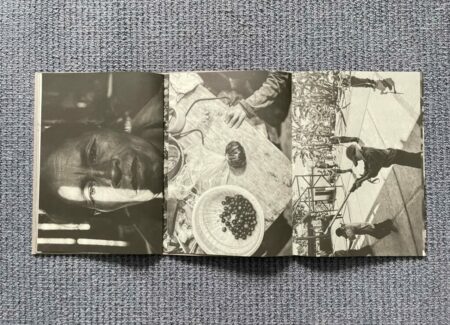

Rodríguez begins our journey with a view up a dusty dirt road that disappears into the clouds, the mountains invisible but looming above, and the next page offers an extended hand pointing, as if to show us the way. When we reach the villages, they are populated by wandering kids, stray dogs, and makeshift tin-roofed buildings, the churches offering the most eye catching architectural features amid the surrounding mountainscape. The rhythms of life then slowly present themselves, from children sleeping in hammocks and eating ice cream from containers to cowboy-hatted men heading off to work in the dark and resting in doorways weary from their labors. Slaughtered cattle, complete with severed heads, offer the first few glimpses of the violence that has permeated this place.

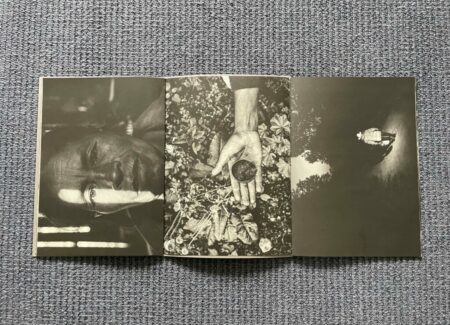

Religion, in many forms and practices, provides a kind of scaffolding for life in the mountains, and Rodríguez follows its influence closely. He shows us baptisms and communions, statues of virgins and saints carried through the fields and streets, and church buildings that anchor the communities. He also documents other Indigenous rituals, where shrines and memorials of flowers and burning candles spring up in the hills and masked actors play out historical fight scenes. And then of course, there are the funerals, and sadly there are plenty for Rodríguez to document; he sensitively captures floral wreaths placed on graves and at locations of deaths, men standing somberly with hats off and holding bouquets of wildflowers, and processions with caskets and wakes that feel a bit too commonplace. Again and again, the community gathers amid these crosses and flowers, the weathered faces smoking cigarettes and mourning yet another now lost.

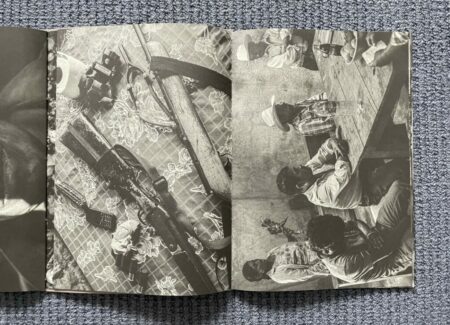

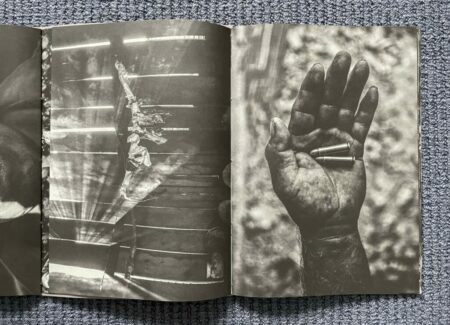

Rodríguez gets closer to the culture of violence as the photobook progresses. Rugged hands hold bullets, a table top still life features worn guns, shotgun shells, a cellphone, and a slingshot, and wary men ride in the back of trucks ready for armed encounters. More dispiriting are the images of younger boys, learning to box and getting trained to wear bandannas and hold toy rifles; one gathering of boys sitting on stairs features most of them awkwardly holding their guns while one boy plays with a yo-yo. Paired with these images of boys being turned into soldiers, the anguish on the aged faces of the older women in town seems consistent, the culture of violence leading to a parade of blank stares and resigned sorrow.

Rodríguez has found an elusive balance in Montaña Roja that intertwines strands of tenderness and hope with more harsh and dispiriting truths. His photographs sensitively document the transformation of the social structure, where the cultivation of the poppy feels both familiar (with its traditional farming dreams of better crops, more rain, and no pests) and intrusively and unavoidably dangerous (with the death and violence that seep into the deepest corners of everyday life). This charged mix of aspiration and fearful endurance ultimately gives Montaña Roja its energy, the cycles playing out with merciless regularity. In the end, its story is both beautiful and bleak, pulling us onward along its seemingly unavoidable paths of conflict.

Collector’s POV: César Rodríguez does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time, As a result, interested collectors should likely connect directly with the photographer via his website (linked in the sidebar).