JTF (just the facts): Published in 2023 Nazraeli Press (here). Hardcover (12 x 15 inches), 110 pages, with 46 quadratone plates. Includes a poem by Pablo Neruda. Design by Jungjin Lee and Chris Pichler. In an edition of 3000 copies. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Jungjin Lee was born in Korea, and started taking photographs in the 1980s while she was a ceramics student in Seoul. Her artistic experience in ceramics, painting, and calligraphy (which she mastered as a child) has influenced her working process in photography. She moved to New York in the 1990s to study photography at New York University, and while at school, Lee was also assisting Robert Frank, and her work was influenced by his artistic attitude. Early in her career, Lee took a trip across the United States and her experience in nature, particularly the desert, has inspired several of her subsequent series.

Lee has developed her own printing technique, where she hand prints her large-format photographs on hanji, a traditional Korean mulberry paper with irregular edges. She brushes a liquid photosensitive emulsion on the raw paper, and then uses a photo enlarger to project an image onto the prepared surface. The texture of the paper and the gestural marks of the brushstrokes create a unique effect – tactile and minimalist at the same time, her photographs resemble charcoal drawings. (This process is extremely time consuming, and in recent years, Lee has begun to combine analog and digital processes.) Lee says that through this meticulous printing, she wants viewers to feel the works as objects.

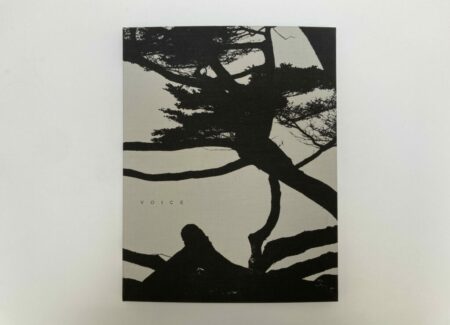

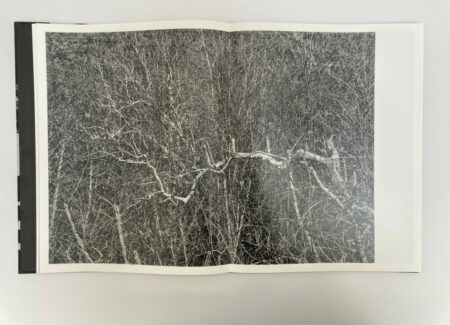

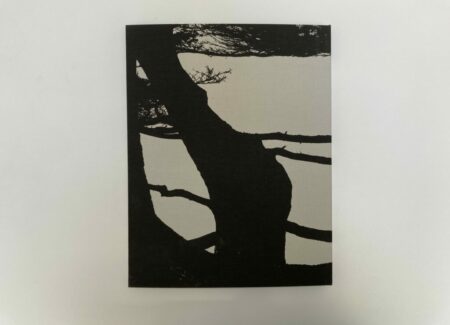

Over the years, Lee has published over a dozen books, and her most recent title is dedicated to her series Voice. Reflecting the physicality of Lee’s large-scale photographs, Voice is an oversized book. A high contrast photograph of tree branches, printed on the cloth cover, envelops the book. The title is elegantly placed on the side in all caps, and repeated again on the spine. All of the photographs are oriented horizontally, and are displayed the same size with a white border around them. Black spreads divide the book into four, more or less equal, sections, and there are no page numbers, captions, or explanatory notes. The book is elegantly designed, the photographs are lushly printed, and it easily lays flat; the only flaw interrupting this experience is an unfortunate warping of the book covers.

Lee describes an image as acting like a poem, and reinforcing that connection, the book opens with “La poesía” by Pablo Neruda (in its original Spanish language), printed with generous white space around it. The poem is about discovering poetry and the love for poetic language. “And it was at that age ….. came the poem / looking for me. I don’t know, don’t really know where / it was, winter or stream.” Neruda’s words set the mood for Lee’s photographs, suggesting that they can also be perceived as poems and her subjects as metaphors. In this way, Lee’s photographs give voice to nature.

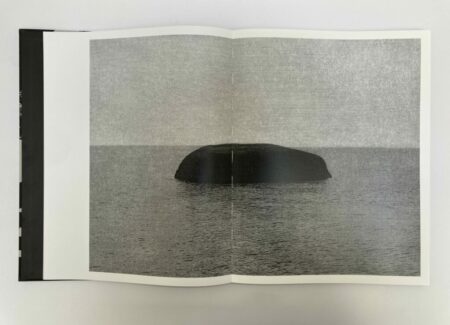

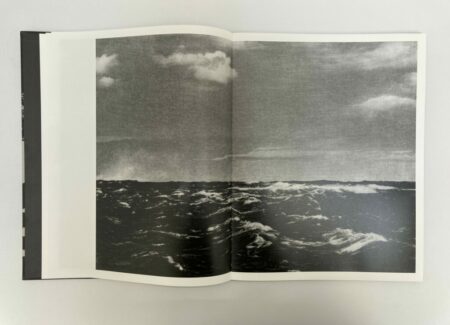

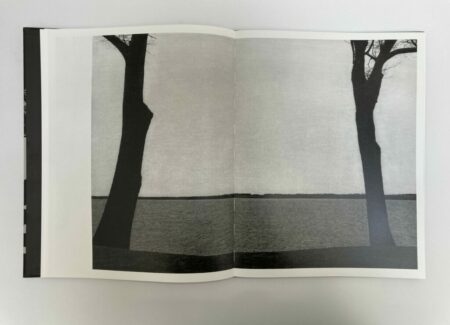

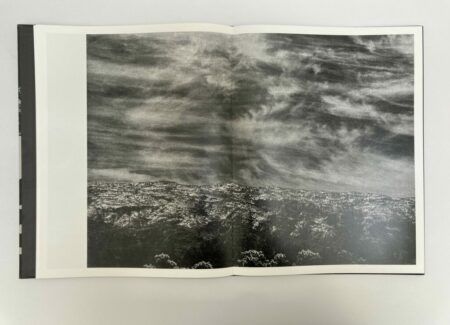

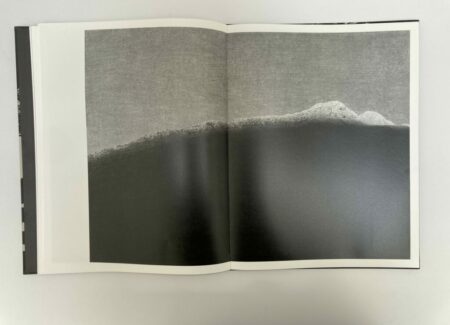

The photographs in the series were taken in 2018 and 2019, while Lee was traveling through the western part of the United States. Lee says about her work, “my images should be seen as metaphors: neither representation of the real world nor expression of its visual beauty, they are a form of meditation.” The images, taken around oceans, mountains, and deserts, simply capture elements of nature, such as rocks, waves, trees, undergrowth, and cacti, and it is this simplicity of subject that often leads to deeper contemplation. The very first photograph in the book shows an oval shaped rock in the water, as its top surface aligns with the horizon. This high contrast minimalistic photograph has a deep texture; both lyrical and universal, it invites the viewer to use her or his imagination to make sense of its form.

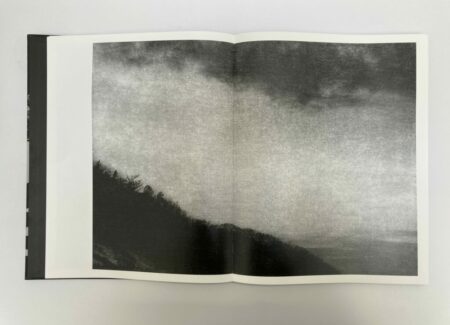

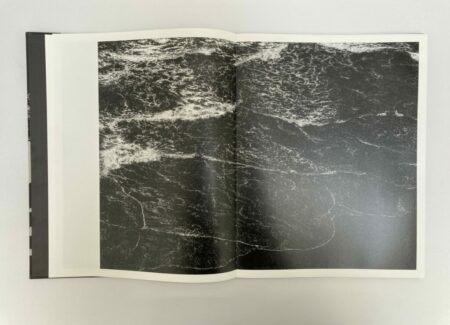

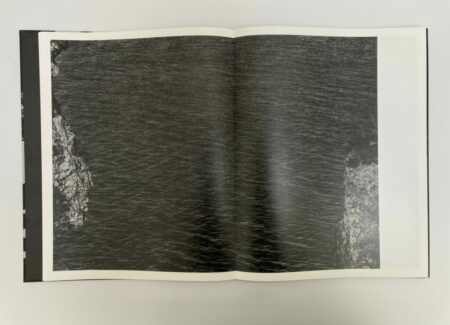

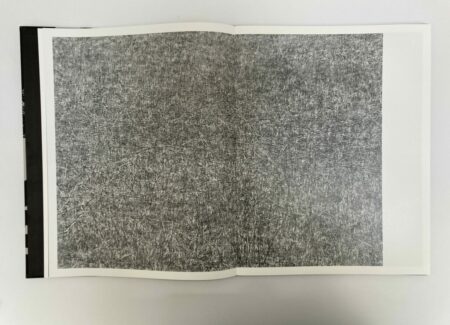

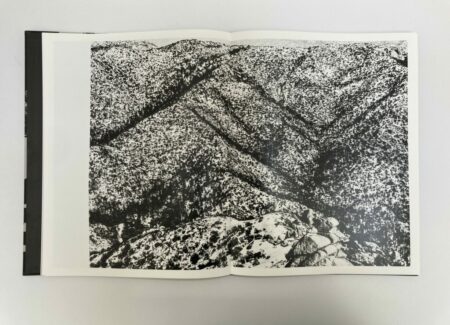

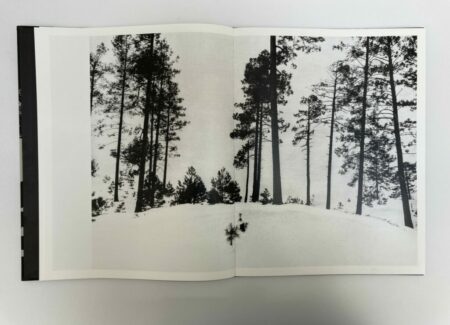

Certain motifs appear repeatedly across the photographs, like horizons, curves between trees or land masses, or a single form becoming a monolith, and there is also often a sense of visual noise, flattening, and indeterminate depth. The image that opens the second section fills the frame with what looks like grass or tree branches, its density is hypnotizing, and printing distortions add additional texture, resulting in a more abstract all-over image. A couple of pages later, another shot looks like a forest covered in snow shot from a hill; the details are merged and distorted, drawing our attention to the patterns and textures of the photograph. And then there is an image of trees standing tall, as the snow and the sky merge into one white background.

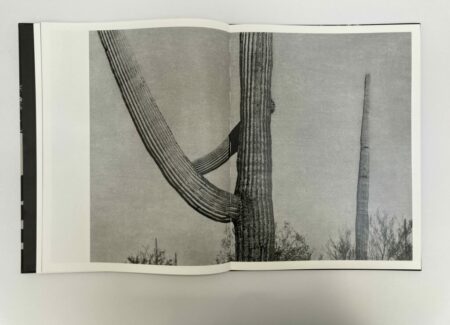

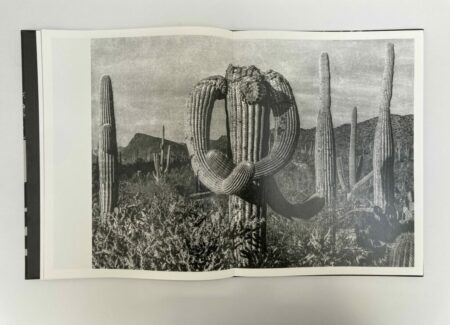

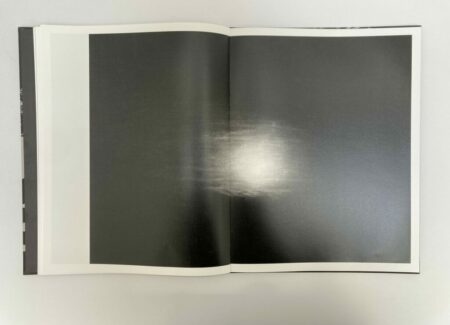

In the final part of the book, the photographs focus on life forms, mostly saguaro cacti and vast open spaces. A high contrast image turns the vertical spire of cacti into abstract black shapes against a gray background, and the images that follow don’t have the same high contrast, but instead shift the attention to the texture of the cacti and their immediate surroundings. But again, the images don’t document a distinct or specific American landscape, they rather reflect a universal idea of a desert. The very last image in the book is a white fluid shape against a dark wash of blackness, like a flare of light.

In asking us to look closely, Voice reveals the strangeness of the familiar, as the photographs document not only surfaces, but symbolize something that cannot be seen. Each of Lee’s images presents a metaphor for an interior state of being. And while the book might not reflect the same physicality as a printed photograph, it gets close, also allowing us to experience and feel the photographs at their own time and pace.

Collector’s POV: Jungjin Lee is represented by Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York (here). Her work has little secondary market history, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.