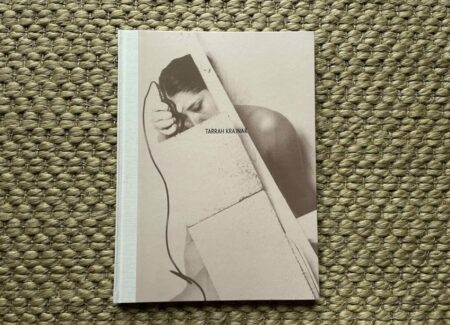

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2022 by TBW Books (here). Casebound muslin wrapped hardcover, 10 x 13.5″, 52 pages, with 16 tritone plates. In an edition of 500 copies. (Cover and spread shots below.)

This body of work was awarded the Jury Prize of the Louis Roederer Discovery Award at Les Rencontres d’Arles in 2021.

Comments/Context: In the past decade in particular, we have seen growing momentum around disassembling the white male canon in photography. This active process of rethinking and rebalancing has taken many forms, from bringing a more diverse range of new photographic voices into focus (in both gallery and museum settings) to questioning the validity and enduring relevance of some of those already firmly placed in the art history books.

For many younger photographers, this wholesale reimagining isn’t happening as an arm’s length intellectual abstraction – these changes of mindset, “gaze”, and approach are much more fundamental, and are being readily incorporated into their work. In its simplest form, this deconstruction process manifests itself as a rejection or replacement of the white male gaze with one that is more inclusive in terms of race, gender, sexual orientation, and other personal identifiers. And in more nuanced examples, the white male gaze isn’t simply being tossed overboard as outdated, prejudiced, sexist, and/or irrelevant, it is being thoughtfully, systematically, and in some cases aggressively examined and wrenched apart, the artists breaking it up from the inside by simultaneously mimicking and incisively undermining its styles.

At first glance, Tarrah Krajnak’s recent nudes might look like the output of an art school assignment – pick a master photographer from the past and make a series of images in that same style, as an exercise in trying to see through his or her eyes. But Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes is much more than a straightforward homage to Edward Weston. By placing herself both behind the camera and in front of it, Krajnak unpacks Weston with plenty of critical insight.

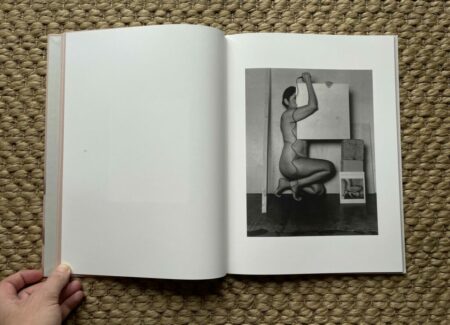

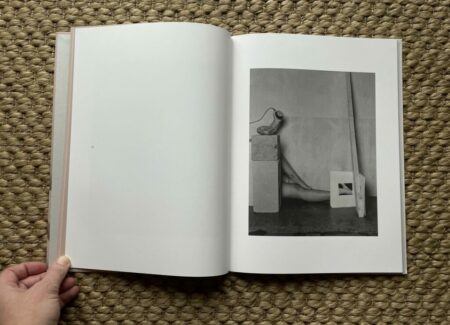

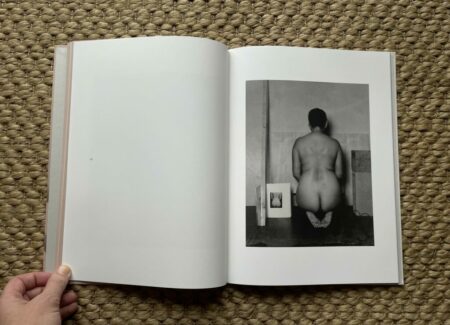

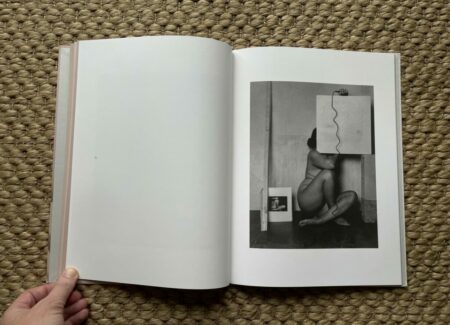

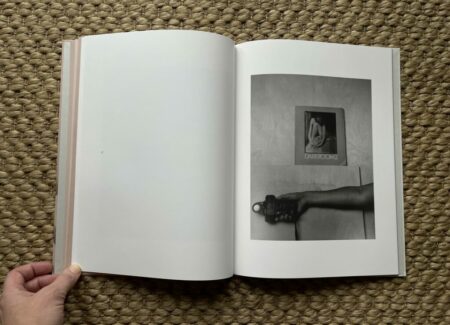

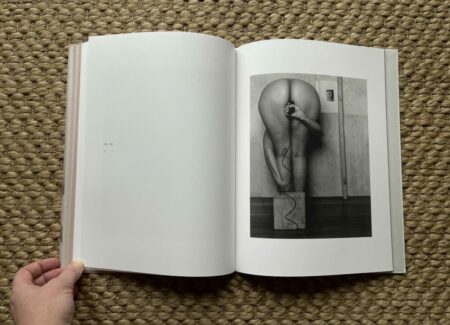

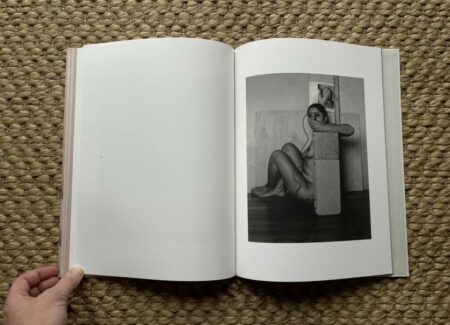

Krajnak starts with two photobooks from her library, Edward Weston Nudes published by Aperture in 1977 and DARKROOM2 published by Lustrum Press in 1979, essentially using them as the foundation on which she builds her own interpretation of their contents. In each setup, she starts with a Weston nude from one of the two books, which she then faithfully recreates in her studio, using cinder blocks, sheets of plywood, and other boards to both hold the book open (so we can see the source image) and to create visual interruptions that help her replicate the formal arrangements in the original pictures.

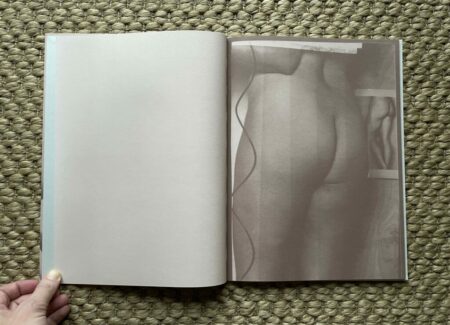

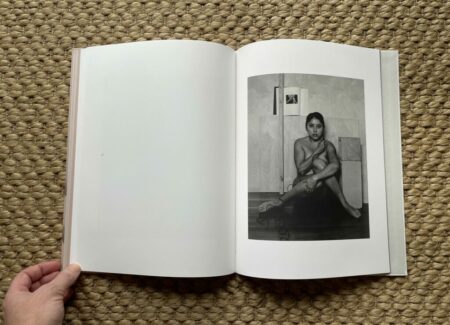

Weston’s nudes have often been held up as elemental Modernist symbols of idealized female beauty, but with the passage of time, we can now of course see that even at their most abstract and formal, they are inherently infused with both his gaze as a heterosexual man and with his choice to portray primarily white models. In the nudes Krajnak has chosen to reconsider (generally from the 1920s and 1930s), the original models were Bertha Wardell and Charis Wilson, both young white women, so when Krajnak substitutes in her own nude body, her status as a Hispanic woman (originally from Peru) immediately challenges that narrow orthodoxy.

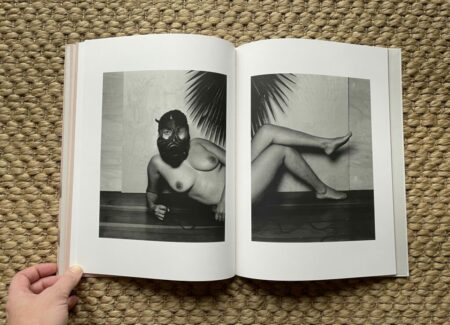

But Krajnak’s doppelgängers are not just studies of the subtle differences between female bodies. Nearly all of the compositions Krajnak selected were framed by Weston in such a way that they crop out the heads of the models, making the interactions anonymous and sculptural; but when Krajnak recreated the pictures in her studio, she generally allows the surroundings to extend a bit further, capturing her head, and often her direct gaze looking back at the camera. Since Krajnak is triggering the shutter with a bulb release visibly placed in her own hand, she is literally replacing Weston’s gaze with a dual-direction female version – one as photographer, the other as subject. And when we see it, Krajnak’s gaze isn’t somehow indirect, submissive, or even blankly deadpan – she glares back at us with unwavering confidence and steely authority, challenging the gaze of the viewer by meeting it head on. This direct confrontation transforms the angles of overlapped arms and bent knees that used to hold our attention, Krajnak’s penetrating eyes, and the agency and personality they represent, powerfully reorienting the dynamics of the visual transaction taking place.

Other works in the series play with exposure shading tests from the darkroom manual, with Krajnak not only recreating the famous head down pose on the cover of the book, but showing the light meter readings and incorporating greyscale strips of alternate shading. Some of the exposures are then further cropped and printed on almond-colored paper at the beginning and end of the photobook, reorienting and relayering the blocked geometries of the plywood boards and the cinder blocks and their relationships to her body. These refrains amplify the sense of deliberate experimentation and multiplication, and of Krajnak iteratively reworking these compositions again and again.

This intentional process leads us back to the “ritual” in the title Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes; Krajnak’s recreations have a feeling of ritual, of tradition being acknowledged but then rebuilt for a new age. What stands out about these images is the changing locus of control. In Weston’s day, he held all the cards and manipulated his sitters like inanimate objects; now Krajnak is in control, and by reimagining these historical icons as self-portraits, she has boldly asserted that bodies can be seen differently. For institutions wrestling with how to update their collections to reflect changing attitudes, this series of nudes is a perfect teaching tool, one that both references the positives and negatives found in the work of the past and offers a freshly innovative interpretation (and critique) of those same standards. Not only are these photographs elegantly refined, they are supremely smart, referencing and upending all that the male gaze represents in one precisely engineered conceptual twist.

Collector’s POV: Tarrah Krajnak is represented by Galerie Thomas Zander in Cologne (here). The works in this photobook are available as a set of 18 gelatin silver prints. Krajnak’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.