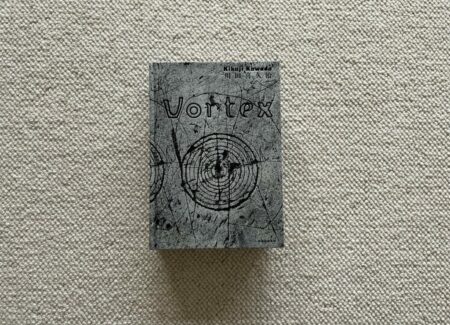

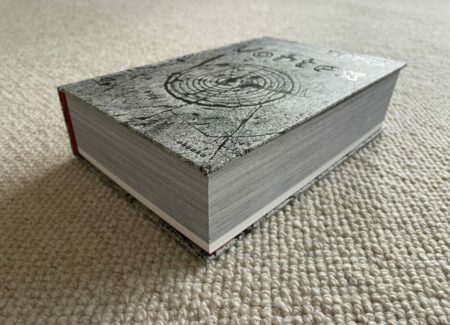

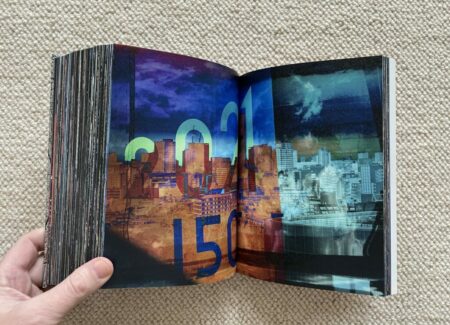

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2022 by Akaaka Art Publishing (here). Hardcover, 21.6 x 15.4 cm, 544 pages. Includes essays (in English/Japanese) by Yoshiaki Kai, Pauline Vermare, and Akiyoshi Taniguchi. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Across the history of photography, when major technological or aesthetic disruptions come along (which has been decently often), it’s a somewhat hidden truth that only a very few master photographers from the old approach successfully adapt to the new reality. Many more never quite make the jump, either stubbornly sticking to what they know, or only putting a timid toe in the water of the new world. Whether in the transition from Pictorialism to Modernism, or from black-and-white to color, we now remember and celebrate those who straddled the chasm or converted more fully, but the lists of those who actually delivered equivalent quality and innovation on both sides tend to be short. When the earthquakes happen in this medium, new photographers tend to aggressively leap into the void, making the break with the old that much more abrupt.

So let’s play a quick game – of the notable photographers who got their start in the mid to late 1960s, and who are now still working, many well in their 80s, who can we name that has successfully launched themselves into the current world of computationally driven, software manipulated digital photography? Again, the list is pretty short, with Gilbert & George, David Hockney, and Lucas Samaras coming to mind (all of whom, by the way, were interested in various kinds of image manipulation early on in their careers); others from that era are of course still making solid work, but few have embraced the power of the new technologies with as much expressive risk-taking innovation as those three.

Based on his recent photobook Vortex, which gathers together images made in the past few years and shared on Instagram, Kikuji Kawada may indeed have a fair claim at joining this very small club. Across his six decade career, Kawada has freely used montage, multiple exposure, image layering, compositing, and other darkroom effects to amplify the atmospheric moods of his images, most notably of course in his 1965 project Chizu (The Map), which ambitiously wrestled with the anguished traumas left behind at Hiroshima. Other projects over the years, including Los Caprichos (as seen in a 2020 gallery show, reviewed here) and The Last Cosmology (as seen in a 2014 gallery show, reviewed here) were similarly expressive, pushing to stretch the limits of Kawada’s unique photographic aesthetics.

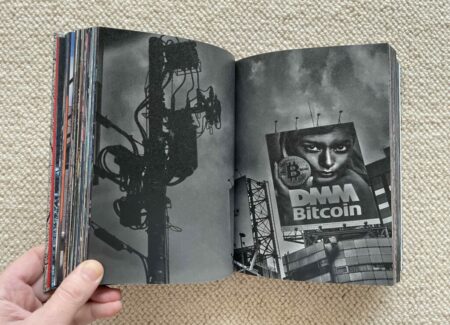

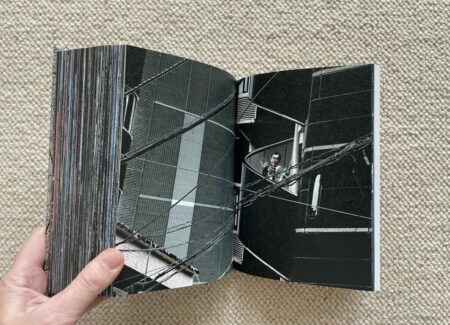

So it’s not entirely unexpected that Kawada might be a willing candidate for embracing what the new tools have to offer, but it’s still altogether impressive that his “late style” (Kawada is now 89) is so comfortably forward-looking. In a sense, Kawada has found new equivalents for most his old ways of working, many of the effects now delivered with more power, flexibility, and granular control than he ever had before. In Vortex, he has taken life in the anonymous city as his central subject, and used the available software manipulations to re-interpret his visual findings and heighten the dark anxious mood. His results provide echoes and connections all the way back to his first images, but with a restless sense of haunted exploration and discovery.

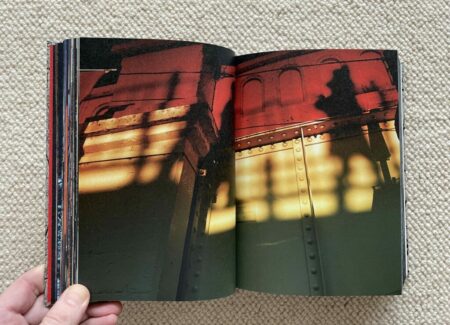

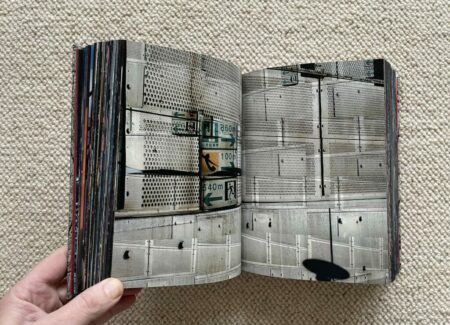

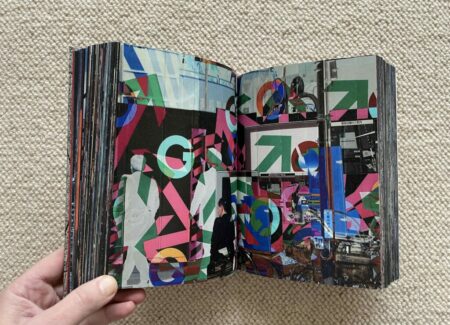

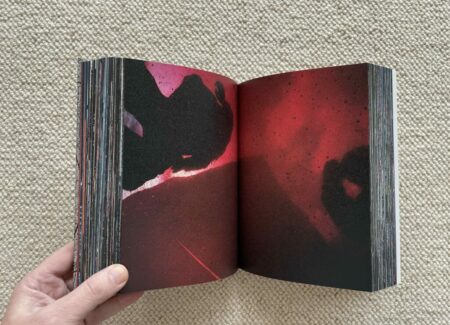

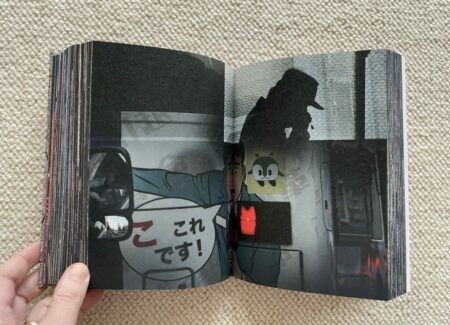

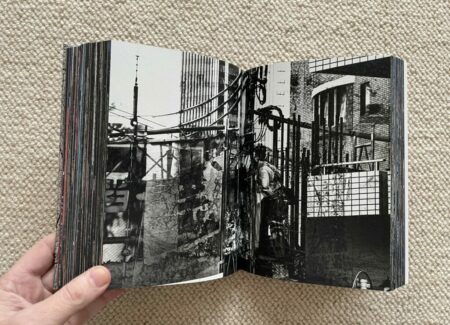

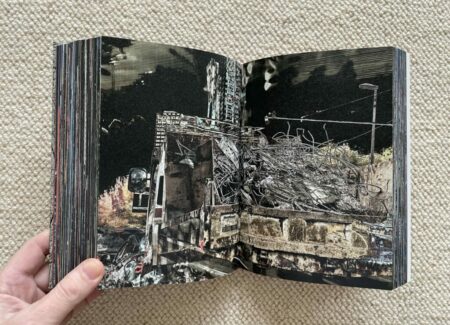

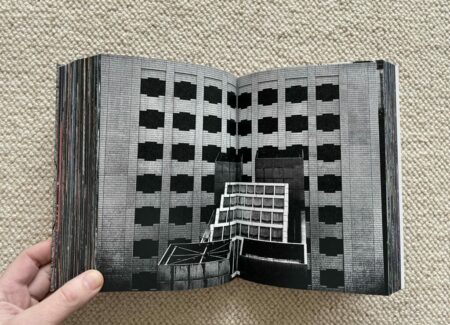

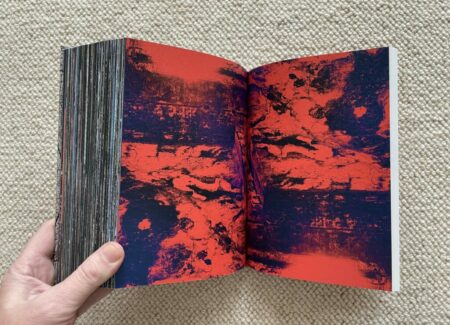

At nearly three inches thick, Vortex is a brick (or a doorstop) of a photobook – intimately sized, but unexpectedly hefty. But its unconventional form does deliver a vague facsimile of the endless, time-independent Instagram scroll where the images first appeared, in that the pictures are all printed full bleed, often in bright saturated colors, and we are asked to page through them, over and over and over, until we get about half way through and think we are near the end, but actually aren’t anywhere close to finished. As an experience, looking at Vortex mimics a sprawling stream of consciousness, with echoes and refrains of subject matter and aesthetics appearing and reappearing, knitting the visuals into a well-integrated whole that ultimately stands as a forceful artistic statement.

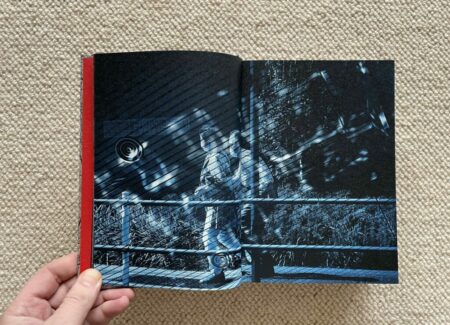

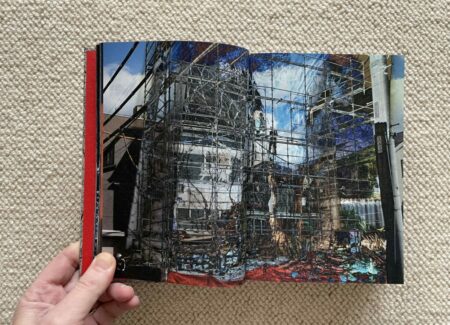

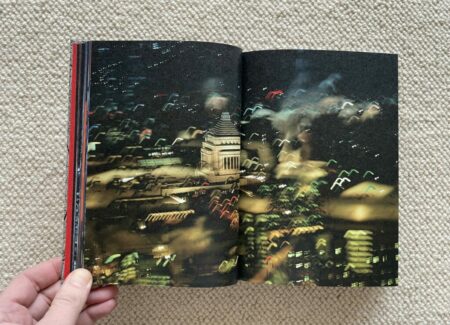

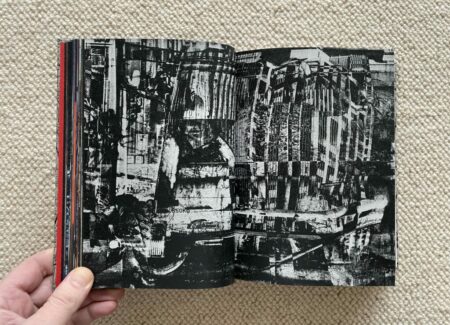

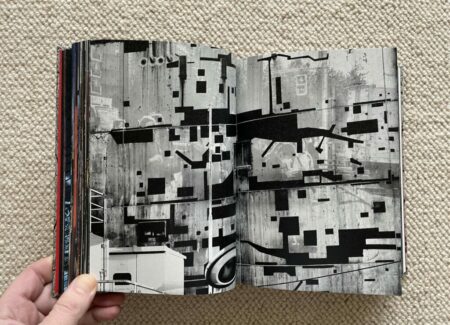

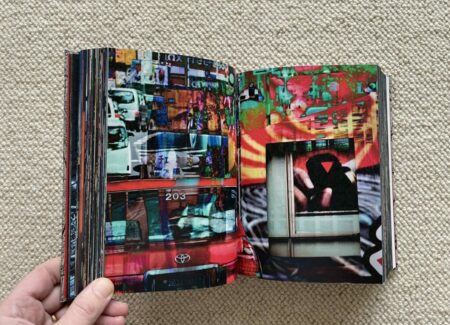

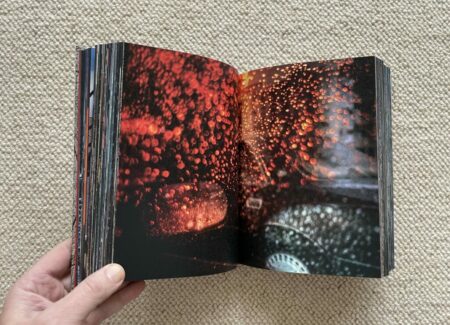

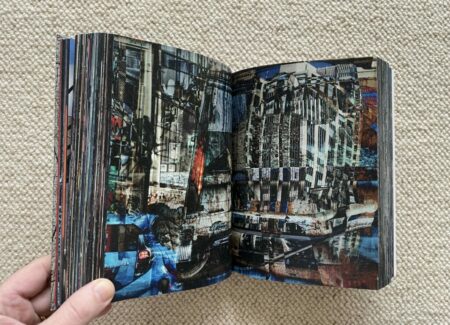

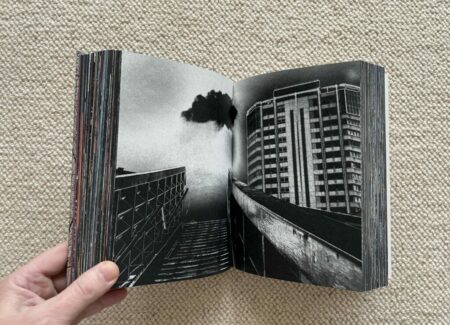

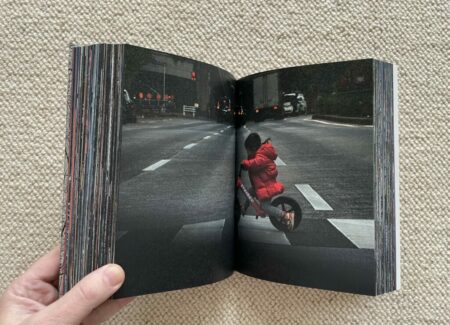

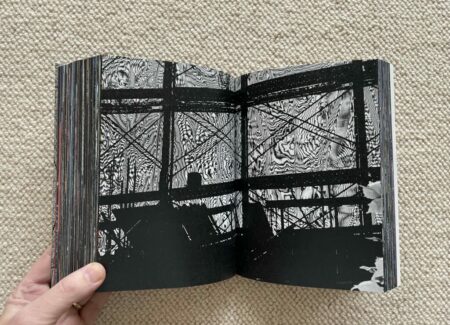

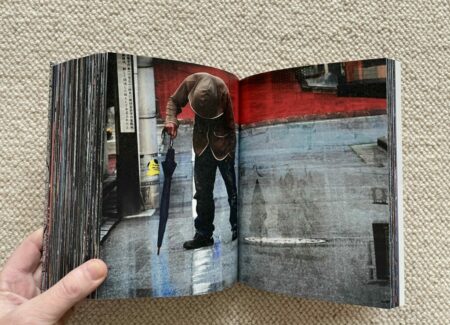

The city in its many forms stands at the center of this project, with images of bustling streets, throngs of pedestrians, skyscrapers, storefronts, construction sites, sidewalks, gutters, streetlights, advertising, and other urban details all catching Kawada’s roving eye. We have been such places before, but Kawada’s city has been re-imagined, the documentary evidence of seeing and observing given a burst of unsettled sensory madness. This new place is on the edge of chaos, where dark contrasts and vibrant tones tussle for attention and the ordinary routines of the day and night shift towards the extraordinary possibilities of dreams and nightmares.

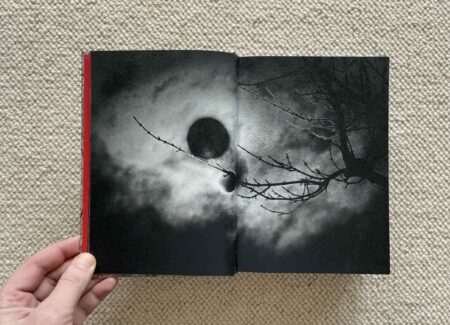

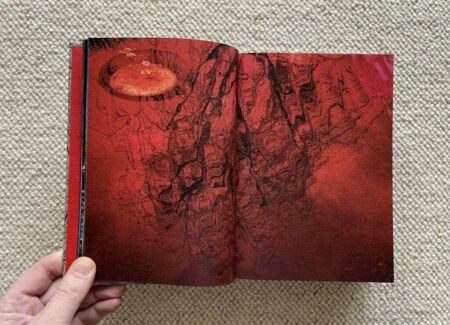

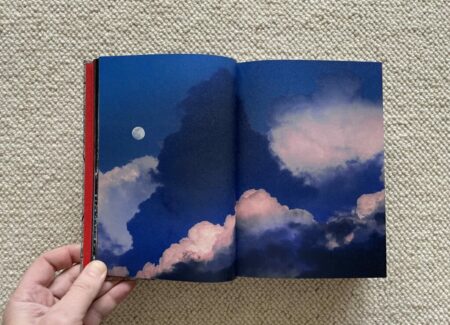

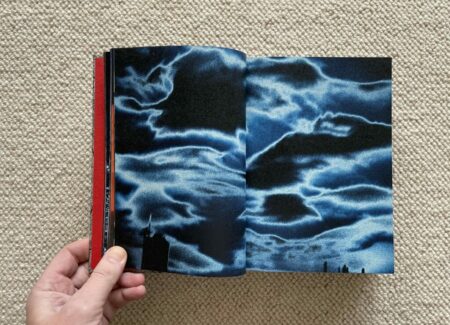

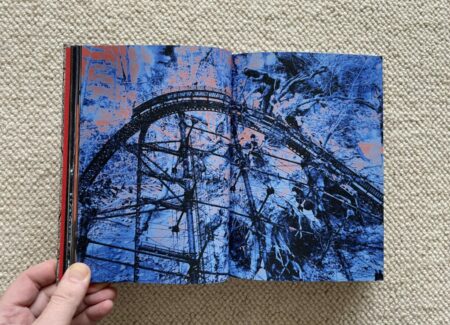

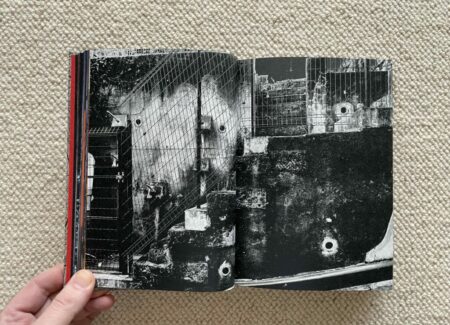

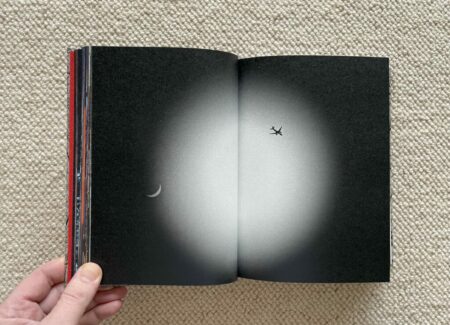

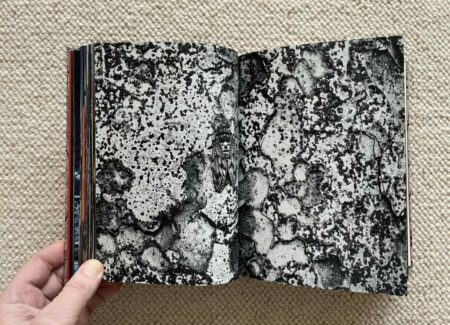

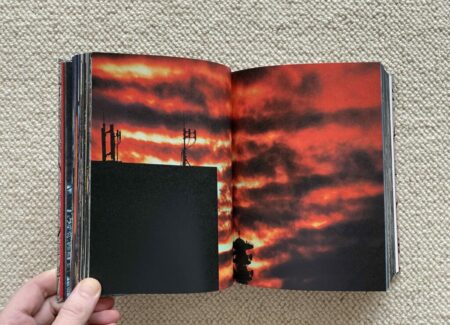

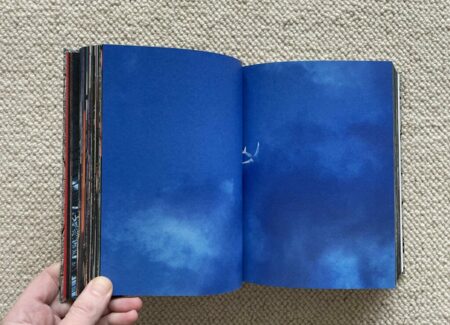

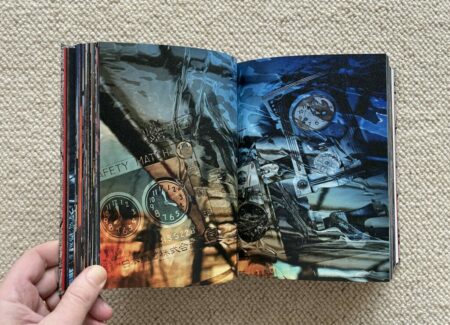

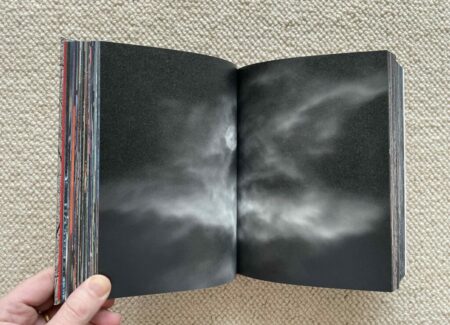

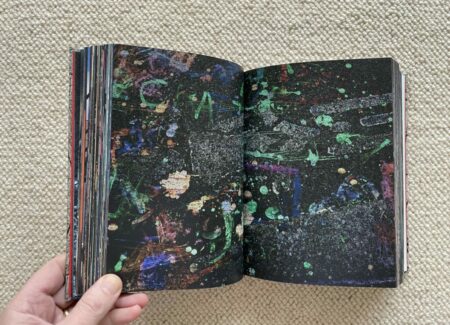

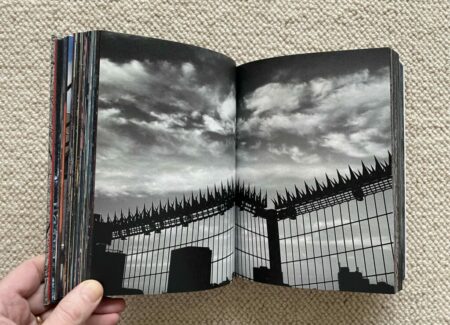

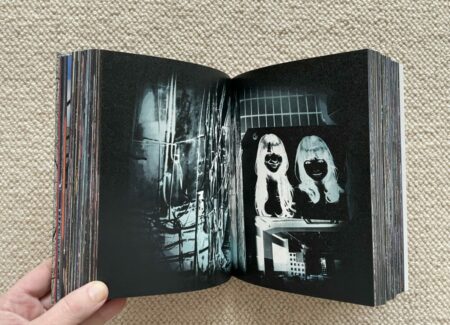

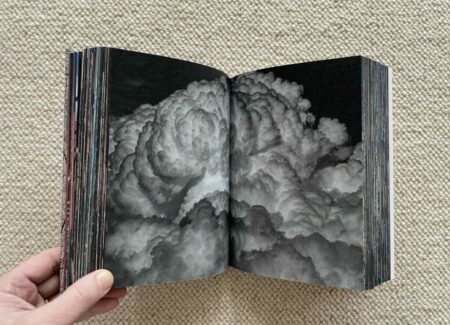

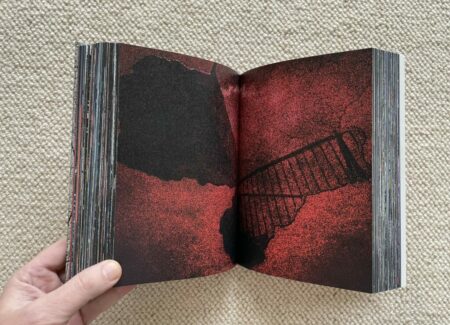

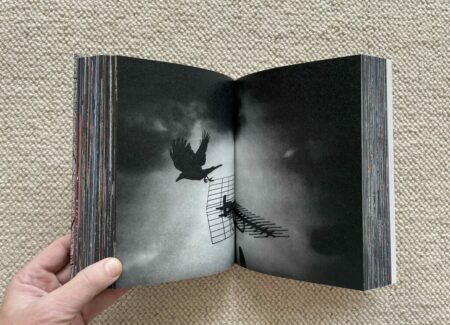

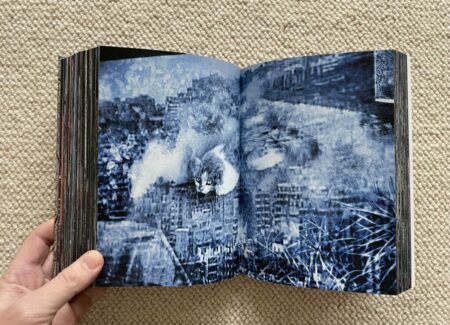

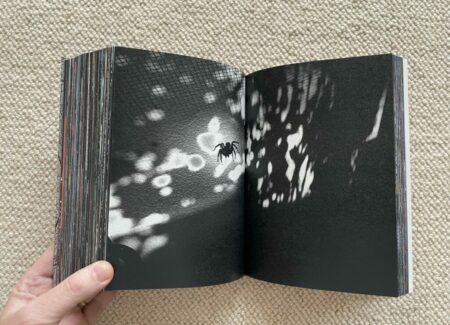

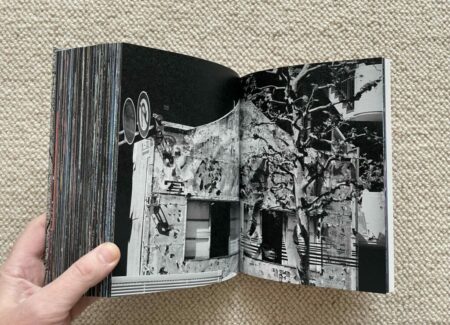

Those familiar with Kawada’s long history of image making will find plenty of motifs here that offer connections to and harmonies with the past. Mottled, stained, cracked, bubbled, scratched, reflected, and otherwise distorted surfaces make plenty of appearances, alluding to stories of damage and decay as well as a kind of pervasive disorientation, where we steady ourselves by looking closely at something that refuses to resolve and becomes almost alien. Kawada is also innately in tune with cycles of of nature, most notably the movements of the sun and moon, which take on ominous and apocalyptic overtones here when seen in their darkest zones. Cloud banks make a particular repeated appearance in Vortex, from bulbous masses to more sinister streaks and bleeds that swim across the hazy (or fiery) skies. These views are then quietly populated by lone airplanes and helicopters, and closer in by dark silhouetted crows, adding yet another layer of implied menace.

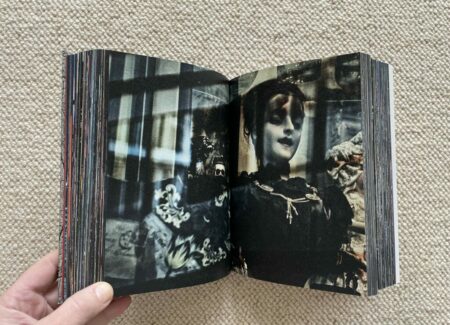

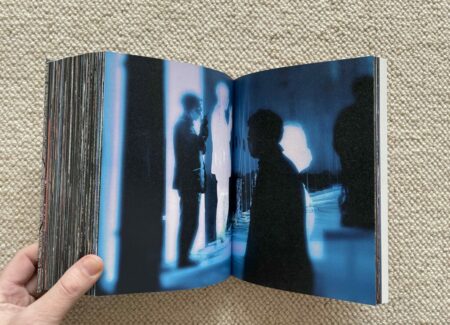

When Kawada turns his attention to the skin of the urban city, in the form of its buildings, walls, alleys, and other built structures, he manipulates his results to give them a feeling of vibration. Again and again, these surfaces seem to dissolve and disassemble right before our eyes, with reflections, eerie color tinting, and other visual tremblings and oscillations making everything unstable. These moments are then populated by shadow figures, masked inhabitants (in the pandemic sense, and in other more inexplicable ways), and various solitary figures in danger or despair. To say the mood is dystopian is perhaps too obvious or literal; it’s more that a simmering catastrophe is waiting to happen, and these snatched impressions are simply evidence of what’s to come.

Seen as one continuous flow, Kawada’s vision as presented in Vortex is often overwhelming, but there are undercurrents of unexpected beauty in this parade of trauma that soften the blow a bit. Kawada’s obsessive looking reinforces the unknowable mystery in our contemporary existence, and makes these flashes of unsettling reality intensely personal. Newness and change wash over us from all directions in his world, leading to a kind of emptiness that Kawada tries to tamp down with a return to elemental cycles.

Most importantly, in crafting this visual statement, Kawada has successfully resisted using his new software tools like toys; while some of the tints, filters, and other features might be recognizable to expert users, for the most part, his manipulations are well integrated, supportive of the story he wants to tell without distracting us with their sparkly effects. In this way, Kawada has masterfully crossed over to the new world of contemporary photography, mixing the strengths of his accumulated past with the possibilities of the now. That such a move feels expressively natural is a testament to Kawada’s feel for the nuances of turning an image into an experience. Edited down to a tight gallery show of 30 0r 40 images, Vortex would hit with undeniable force and authority; as seen in a sweep of hundreds of pictures in your hands, the impact is somewhat more diffuse and enveloping, the uncertain spirit of our shifting age communicated like a secret.

Collector’s POV: Kikuji Kawada is represented by L. Parker Stephenson Photographs in New York (here), Michael Hoppen Gallery in London (here), and PGI in Tokyo (here). Aside from the reselling of Kawada’s photobooks, there is little secondary market history for his work. As such, gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.