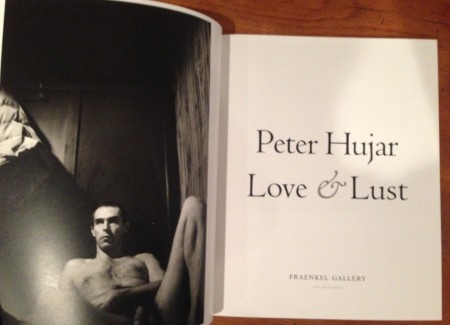

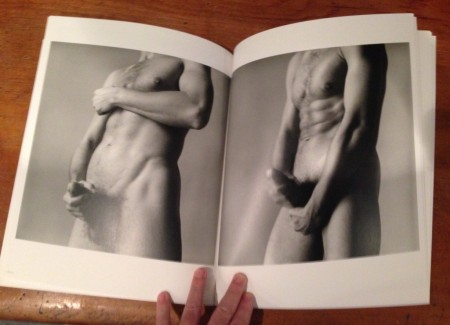

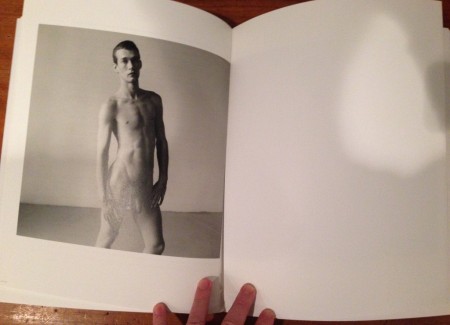

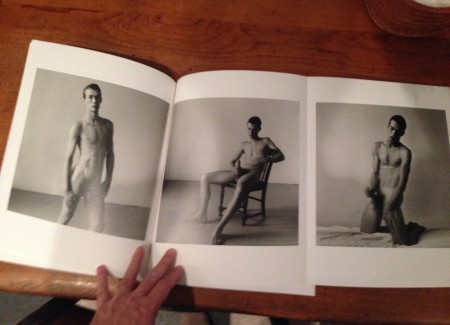

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2013 by Fraenkel Gallery (here), in conjunction with an exhibition (here) of prints by Hujar. Softcover in slipcase (11×14 inches), 82 pages, with 37 tritone reproductions. Includes essays by Jeffrey Fraenkel, Vince Aletti, and Stephen Koch, along with an interview from December, 1989, between Fran Lebowitz and Thomas Sokolowski. (Spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Peter Hujar’s photographs of naked young men exhibit an awareness that his subject has a dangerous past. It’s not certain why or how or when this happened. The male nude was once the ultimate test of skill for Western sculptors. When Praxiteles, Michelangelo, Bernini, or Rodin carved or cast men’s bodies in stone or metal, the results were often glorified in temples, plazas, churches, palaces, art schools, and museums.

If necessary, should one of these figures spark erotic flames in a spectator, moral conflagration could be doused by citing the men’s fictional status as characters from Greek myth or the Bible. A man standing naked before the world conveyed nobility. Roman Emperors and American presidents have been posed in the altogether without provoking government censorship or audible snickering.

The male nude is notably less visible in the history of Western painting, with a sharp drop-off in numbers after the death of Michelangelo. When picturing naked figures of either gender, Rubens, Velázquez, Boucher, Ingres, Delacroix, Courbet, Manet, Picasso, and Matisse—as well as their patrons and audiences— clearly preferred the soft, curvy flesh of naked women to the square muscular torsos of naked men. (Cezanne is an exception.)

In fine art photography, the subject has been yet further marginalized within the canon. Until the 1970s, such images were more apt to invite police raids than find acceptance in textbooks or art institutions. Picture material of this sort was mainly confined to books and magazines hidden behind the counters of seedy newsstands.

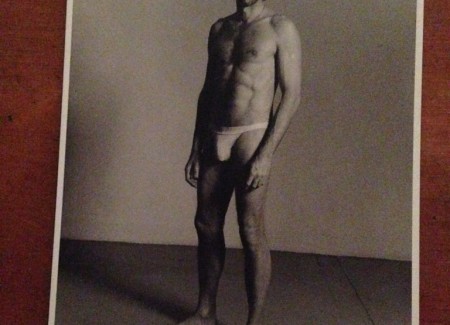

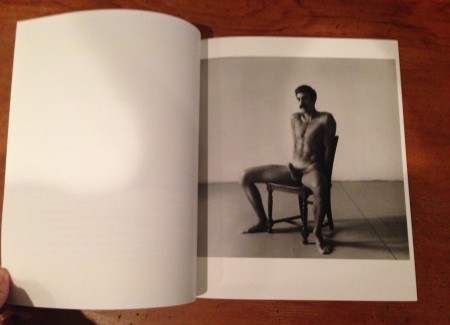

This secret history can be detected in the pages of Love & Lust. Fully half of these photographs have not been published or exhibited before. Done mainly in a studio setting between 1967 and 1986, as gay culture in New York was emerging from decades of repression, Hujar’s portraits relied on that community as participants as well as potential consumers.

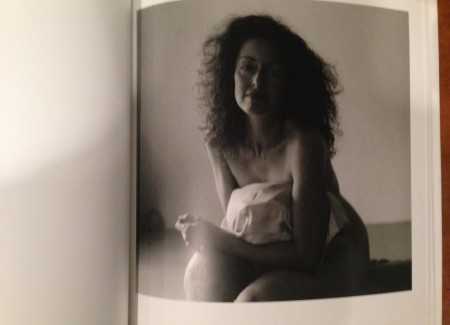

Most of the portraits are of solitary figures, either the artist himself or young men who were friends or friends of friends. Except for a fully clothed portrait of John Cage and Merce Cunningham, everyone here is naked or nearly so. (There are also four portraits of women alone, including one of the photographer Lynn Davis, seated on a bed and hugging a pillow to her chest.)

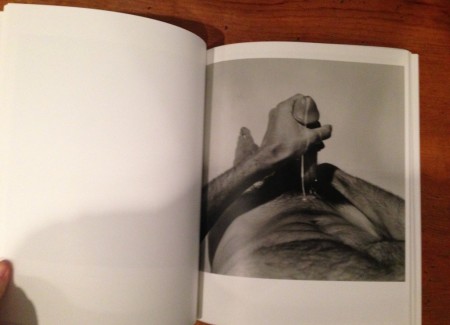

Not content to situate himself within the homoerotic tradition of the male nude established by photographers F. Holland Day, Baron von Gloeden, George Platt Lynes, and Minor White, with its decorous suggestions that some men might enjoy other men as erotic fantasies, Hujar risked being labeled a pornographer by also depicting some of his subjects with erections or while masturbating. There is even a close-up of a hand holding a penis after orgasm.

This was bracing stuff in the 1970s and in some ways remains so. As the NYT photography critic Gene Thornton wrote in a prim review of a 1978 exhibition of male nudes at the Marcuse Pfeiffer Gallery, where Hujar was one of the featured artists, “there is something disconcerting about the sight of a man’s naked body being presented primarily as a sexual object.” (He might have asked, but didn’t, why women are portrayed in this fashion without upsetting male critics.) Nonetheless, one does not have to endorse Thornton’s silly reaction—he called for “old-fashioned prudery when the unclothed human body is a man’s body”—to question the artistic success of these pictures.

Stephen Koch makes a gallant case for them in his essay on a 1976 triptych of the dancer Bruce de Sainte Croix jerking off. Hujar “knew precisely what he did and did not want,” writes Koch. “The triptych must not be clinical or psychological. Nor could there be any slumming in pornography. The triptych must not induce arousal, erection, or orgasm. It had to consummate them. He wanted his camera to see the otherwise unseen bond between the male body and the male soul. And as with all his work, it had to be beautiful—beautiful enough to change the history of art.”

However overheated Koch may sound, he is correct in identifying Hujar’s high-minded ambitions. The photographic treatment of this sweaty, perilous subject is understated, classical. The lighting is even, neither noirish in its shadows nor washed-out with blinding flash. Whether the camera can ever reveal intangibles such as human souls—or the mind-bending intensity of an orgasm–is another matter.

Koch compares Sainte Croix in Hujar’s first panel to Michelangelo’s “David,” both of them mingling “courage with vulnerability.” A better comparison (at least when looking at the last panel) might be with Bernini’s “St. Teresa in Ecstasy,” which portrays the sainted woman in the throes of what seems to be an even more familiar and transporting experience than religious joy. I’m guessing that Hujar had also seen Andy Warhol’s 1964 film “Blowjob,” which focuses on a young man’s face for 35 minutes as he receives oral sex. (It is rumored that five men’s mouths were needed to complete the below-the-camera-level action.)

Hujar knew, as did Warhol, that picturing a man with an erection was defying centuries of fine-art tradition. Such images were found on the walls of Pompei’s outhouses, not in galleries or museums. Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings of men in a state of arousal were cartoons designed to entertain himself or friends. It’s the viewer’s stumbling into what is usually a private space, a man having sex with himself, that continues to give these pictures their shock value. Jeff Koons caused similar embarrassment in 1991 with his “Made in Heaven” series, photographic portraits of the artist and his wife, the former porn star Cicciolina, fucking.

I’m not sure it does a service to elevate Hujar’s work into a marbled pantheon with Renaissance masterworks like Michelangelo’s “David,” which actually did change the history of art, when the strength of the portraits in Love & Lust derives from their being a record of New York’s downtown gay demi-monde in the ‘70s. That place and time had its own atmosphere, economy, friendships, and personalities.

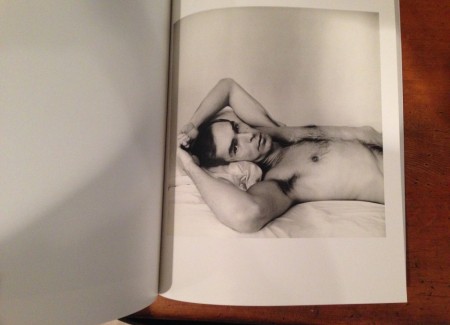

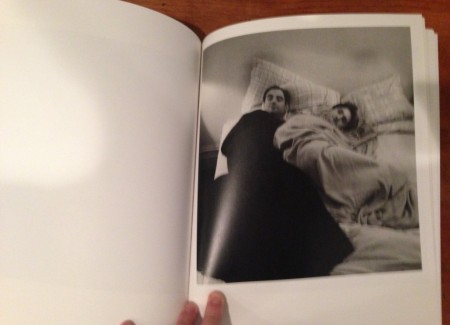

Hujar’s refined sensibility filters this milieu and commemorates it in a studio setting. There aren’t as many half-length recumbent portraits as in his 1977 book “Pictures in Life and Death”–the pose was one of his favorites, indeed, almost a signature—but beds are often the stage for the moods and actions here. The artist Paul Thek masturbates on his back with utter dedication (1967), while the photographer Gary Schneider, who was also Hujar’s printer, sits with the covers pulled up around himself and his partner, the actor John Erdman, the two of them looking like a pair of sleepy-eyed raccoons (1986).

Hujar has never received the public acclaim given Robert Mapplethorpe. They circled each other warily in the ‘70s and ‘80s, with Hujar openly disliking his younger colleague and accusing him of artistic theft. (The writer Patricia Morrisroe once compared their rivalry to that of Mozart and Salieri.) This publication and exhibition are designed to present Hujar as a pioneer, years ahead of Mapplethorpe in his sexual candor, as well as an artist whose photographs are less swank and affected.

Both events mark a surge of interest in Hujar’s life and work. He is a major character in “Fire in the Belly,” C. Carr’s 2012 excellent biography of David Wojnarowicz. (The artist was Hujar’s lover and is twice portrayed in Love & Lust.) A traveling retrospective is being planned for 2015 by curator Joel Smith of the Morgan Library, which recently purchased a cache of Hujar material, including 100 prints, the complete black-and-white contact sheets, correspondence, business records, and ephemera.

Hujar died of AIDS in 1987, long enough to witness the Culture Wars of that decade but before the 1990 trial of the Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati for exhibiting Mapplethorpe’s photographs of naked men and children. The explicit images in Love & Lust are unlikely to cause similar outrage–or a boost in his prices: Mapplethorpe’s soon doubled in the wake of his controversy. Public museums have learned to be extremely careful displaying risky material, and the Internet has inundated the world with porn and with art that could be mistaken for porn. Instead of being publicly denounced by U.S. Senators, Hujar seems destined to be known and appreciated primarily within the smaller, less glamorous circles of art photography.

Collector’s POV: The estate of Peter Hujar is represented by Pace/MacGill Gallery in New York (here) and Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco (here). Hujar’s work has only been intermittently available in the secondary markets in the past decade; recent prices have generally ranged between $2000 and $25000.