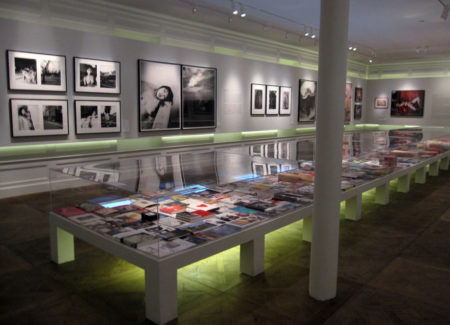

JTF (just the facts): A retrospective exhibit, containing a wide range of black and white and color photographs, photobooks, and other ephemera, hung in a series of connected gallery spaces on two floors of the museum. Summary background information on the works on display is provided below, although process details, dimensions, and edition sizes were not provided:

- 80 photographs or photographic artworks dated between 1971 and 2015 (though some are later prints), including 49 framed black-and-white prints

- 6 framed black-and-white diptychs

- 12 framed color prints

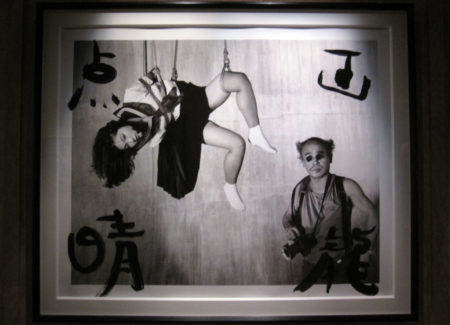

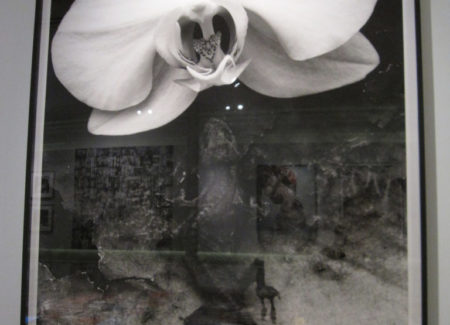

- 2 framed black-and-white prints with Sumi ink

- 7 framed black-and-white prints with acrylic paint

- 1 set of 101 individually framed black-and-white photographs

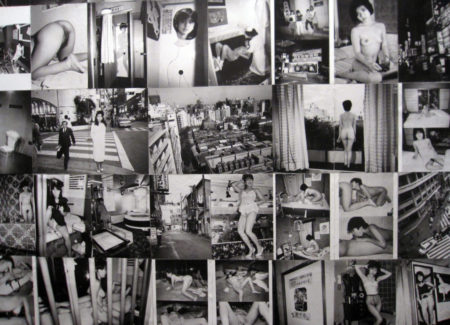

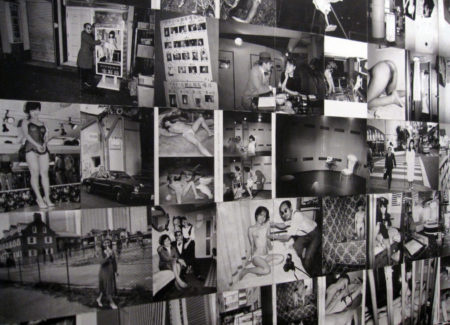

- 1 unframed selection of 100-plus black-and-white photographs

- 1 unframed selection of 500 color Polaroids

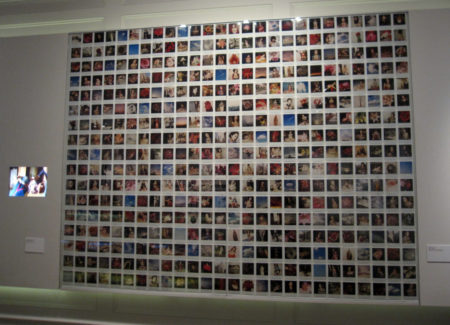

- 1 selection of 1050 color transparencies in a large-format frame

In addition to these works, the show includes 1 1964 Tokyo Olympics official souvenir book; 1 photo album; 3 woodblock prints; 5 video excerpts from Travis Klose’s Arakimentari (2004); and a vitrine containing several hundred photobooks. The exhibition also includes two photographic giclee prints by Juergen Teller.

(Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: Sex is life, as we don’t need Freud to tell us. And humans have been making erotic images as long as they’ve been making art. How those images are made, however, matters greatly. Can we take pleasure in pictures created by exploiting or abusing others? And do we always know what exploitation or abuse looks like?

The Museum of Sex tackles these and other thorny questions in this excellent survey of the work of controversial Japanese photographer Nobuyoshi Araki, who usually refers to himself by his surname only. Araki is best known for blurring the line between erotic art and pornography, most famously in photographs of nude or partially nude young women in intricately knotted rope restraints. (He is a master of the Japanese style of rope play known as kinbaku-bi, or “the beauty of tight binding.”)

But while the show’s focus is on Araki’s erotica (this is a museum whose lobby is a sex shop, after all), Mark Snyder, the museum’s director of exhibitions, and guest curator Maggie Mustard—an authority on Japanese photography—also give him his due as an artist of extraordinary productivity and range. Along with Araki’s elaborately staged bondage photographs, the show presents gamier images taken in Tokyo’s sex clubs and love hotels, unexpectedly arousing shots of orchids, cracks in sidewalks, and cut fruit, and pictures of quotidian city life.

It also includes Araki’s Xerox Photo Album, self-published in 1970—the 25th anniversary of America’s atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—in which nearly illegible images conjure burned bodies and devastated landscapes. It is a reminder of Araki’s importance in the critical shift in Japanese photography during the 1970s from kindai (the modern) to gendai (the contemporary), with its blurring of distinctions between art and photography. Most important, through a careful organizing of material—sections include “Controversy,” “Self and the Artist,” and “Ritual and Obsession”—and extensive wall texts, the curators confront, among other subjects, the problematic power dynamic between Araki and his models, Japanese fetishizing of schoolgirls and Western fetishizing of East Asian women, and the artist’s obsessive-compulsive personality.

The two-floor exhibition, which is the first major show of Araki’s work in the United States, features over-the-top staging not usually associated with museum retrospectives. A narrow, dark stairwell leads to a passageway lined with rope webbing and ending in a large, dramatically spot-lit photograph of a woman in an open kimono suspended in midair by cords. Elaborately coiffed and made up, she dangles serenely, a flower between her open legs barely covering her vagina.

Within, more large-scale photographs hang on rough plywood walls. An image of a heavily tattooed man and a preternaturally pale woman having sex is accompanied by a discussion of Araki’s place as a transgressor in Japan, where tattooing—a sign of membership Japan’s organized crime syndicates—is frowned upon, and obscenity is illegal. In the past, Araki has been arrested and his work confiscated by authorities. In spite of this, or perhaps because of it, he is a celebrity at home and abroad whose fans include Lady Gaga (seen here in a suggestive, but relatively tame photo) and Björk, who enthuses about him in Travis Klose’s documentary film Arakimentari (2004), excerpted throughout the show.

Further on, more photographs of calm-faced, trussed-up women—including an image where the real turn-on is the subject’s smeared lipstick and the faint impressions on her skin left by a straw mat—are paired with video interviews with two of the pictures’ subjects. Many of Araki’s models have engaged in long-term sexual and creative partnerships with him, and most, including the women on camera, seem at ease with this arrangement, clearly considering themselves as much collaborators as subjects. At the same time, however, a wall text ponders how Araki’s fame might be dictating, subtly or not, the dynamics of those relationships and the conditions of consent.

One text points to a woman’s allegations, made last August on Facebook, that Araki behaved inappropriately with her on a commercial shoot when she was 19. Since the opening of the show, a model known as KaoRi—who appears here in a series of black-and-white photographs spattered with blue and red paint—has accused Araki of financial and artistic (though not sexual) exploitation. At her request, the exhibition’s wall text no longer refers to her as Araki’s lover.

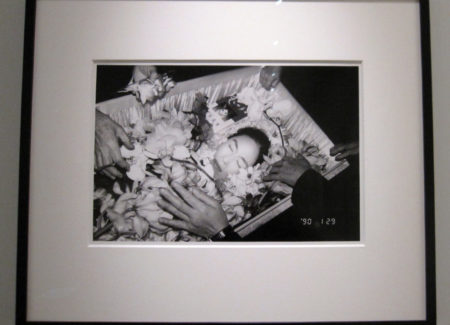

One floor up, the second half of the exhibition opens with four photographs from Araki’s 1971 series “Sentimental Journey,” which he made while on honeymoon with his beloved wife, Yoko. These quiet images, pioneering in their time for their ordinariness, show Yoko nude in bed post-coitus, asleep in a boat, and seated primly, with her purse in front of her, on a train. They are followed by a heartbreaking picture of Yoko in her coffin after her 1990 death from ovarian cancer.

Running down the middle of the gallery, an enormous vitrine containing hundreds of the more than 500 photo books made by Araki over the course of his career suggests that this may be his most generative medium. The books include such famed titles as Sentimental Journey/Winter Journey (1991), which combines photographs from “Sentimental Journey” with documentation of Araki and Yoko’s final years together ; Tokyo Love (1995), a collaboration with American photographer Nan Goldin; Tokyo Radiation (2010), Araki’s visual account of his radiation therapy following a diagnosis of prostate cancer; and many, many collections of photographs of Japanese housewives, who apply to him to be photographed in the nude.

Nearby is a vast grid of black-and-white photographs, taken in Tokyo’s red-light district, of live sex shows and prostitutes with their customers. Interspersed among these unvarnished images of sexual encounters are shots of city train stations, skylines, and buildings, while a number of diptychs pair shots of nude girls sleeping, bathing, and smoking with studies of skies and streets. Ina similar fashion, a gang of color Polaroids jumbles pictures of women, toys, clouds, flowers, cats, and dead lizards.

Erotic prints from Edo-era Japan paired with ravishing color photographs made to imitate them definitely made me—and other visitors to the show, I noticed—breathe a bit faster. But by that time, Araki’s sexually explicit work was beginning to ring hollow, while his melancholic pictures of garden tables in the rain and hurrying commuters were looking increasingly authentic. As the show winds on, its relentless, achronological churn of nudes, still lifes, and urban scenes makes it clear that Araki’s real obsession—as videos of him sweating and crouched behind his camera suggest—is not sex, but photography, as problematic as that work can sometimes be.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum show, there are, of course, no posted prices. Nobuyoshi Araki is represented by Anton Kern Gallery in New York (here) and Taka Ishii Gallery in Tokyo (here), among others. Araki’s work (both photographic prints and photobooks) is routinely available in the secondary markets, running the gamut from large sets of images to single Polaroids. Recent prices have ranged between roughly $1000 and $191000.

Excellent show!

Only disappointment were no ‘spermanko’ photos and the photos that they removed due to recent controversy with model.

Curator did a truly outstanding job on the installation!