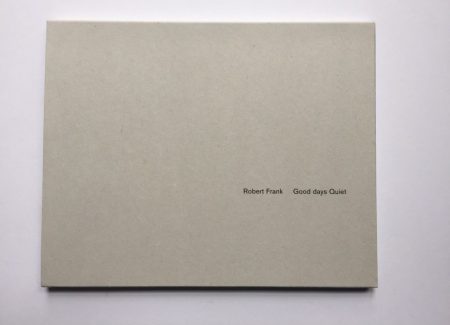

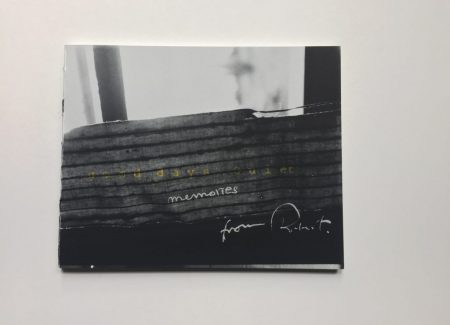

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2019 by Steidl (here). Softcover in cardboard slipcase, unpaginated, with sixty-four pages and thirty-nine photographs, 10 x 8 inches. Designed by Robert Frank, A-Chan, and Gerhard Steidl. (Cover shot and spreads below.)

Comments/Context: Is it still possible to write more words about Robert Frank? Standing in front of my bookshelf, where an entire section pertains to him, I think of the words already written, during this past week and in the decades before. And the answer is ‘No. Not really.’ Nevertheless, I begin to pull out some of his books.

Looking at Frank’s photographs, the early ones taken in Europe and South America, words feel unneeded because they hardly deepen, impart, or attach anything meaningful to the kindness of flowers, the quiet chatter of empty chairs, or the, at times conflicted, romance found in the people observed, no matter whether these were bankers, miners, or mourners. Everything is there, within the pictures, ready to be seen and sensed. In the case of The Americans, words diminish instead; they take away. Frank’s photographs insist on silence. Another word that comes to mind is ‘insinuate’. But despite its subtleties, Frank’s work was never oblique, slick, or secretive. Perhaps because he was an avid reader throughout his life, he was sensitive to phoniness and suspicious of words, particularly those explaining photography.

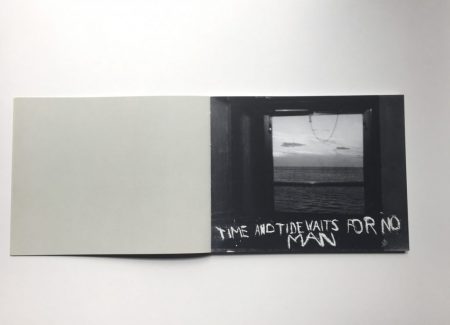

Only when I look at his later photographs, the Polaroids, the rustle of language feels welcoming and comforting. Partly because Frank himself decided to merge the verbal and the visual within them, to both dissolve the chaos and add to the mystery: writing, painting, and scratching words and small phrases, on, into, and beyond his prints and negatives. Maybe for this reason I think of his Polaroids less as photographs and more as images.

Linguistically speaking, photographs are pictures drawn with light. Tracing its etymological origin, the word ‘picture’, refers to a surface – ‘adorned’, ‘decorated’, or ‘sculpted’ – to how it was made, as opposed to what it evokes, emotionally and within the viewer’s imagination.

As a photographer, Frank never believed in objectivity, the decisive moment, or a single truth. Instead he relied on what he saw, and explored how his response could become meaningful to others. And while his beginnings were dedicated to the pursuit of the ‘perfect’ single image, Frank’s understanding of perfection did not conform to photography’s commercially or otherwise established aesthetic standards. From today’s perspective, it appears inevitable that Frank’s persistent rejection of taking pictures that provide conclusive statements or unanimous responses, would result in the making of The Americans – and ultimately in his self-proclaimed abandonment of still photography.

In the early 1970s, however, Frank returned to still photography, and increasingly broke, questioned, and reassembled the semantics and impact of the single image – and in doing so, of photography as an artistic medium. The decade-long hiatus from personal photographic projects and his foray into filmmaking, but perhaps more poignantly, a series of ruptures in his personal life – including the divorce from his first wife, the artist Mary Frank; the tragic death of his daughter Andrea; the disappearance of the cinematographer and friend Danny Seymour; as well as his relationship with the artist (and future wife) June Leaf – culminated not only in a move away from New York to Mabou, Nova Scotia, but also in a new approach towards photography. According to Frank, the use of Polaroids and the inclusion of language enabled him to get away from “that picture – the idea of a picture.” It allowed him “to show how I am myself . . . to show my interior against the landscape I’m in.”

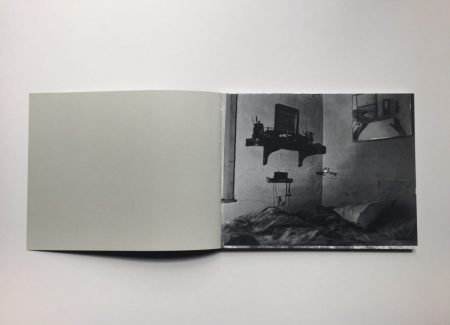

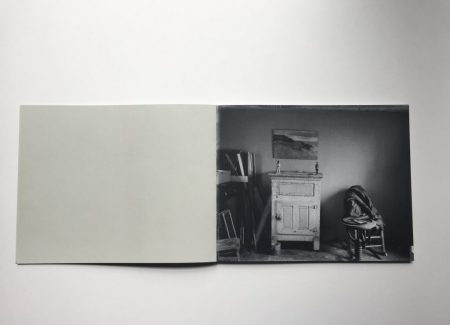

This profound feeling of intimacy, attachment, and love permeates almost every page of Good days Quiet, the final book published in Frank’s lifetime. Uniting landscapes, interiors, portraits, and still-lifes, the book opens with a corner-view of Frank’s and Leaf’s bedroom, where two shelves hold small objects, figurines, and cables. Barren walls reflect the light of a lamp sitting somewhere beyond the frame and accentuate the wrinkled sheets and crumpled pillows. It is a modest, quiet room devoid of people, but their presence is felt everywhere. So this is where they sleep, I think, a bit shy, as if I am looking at something that I shouldn’t.

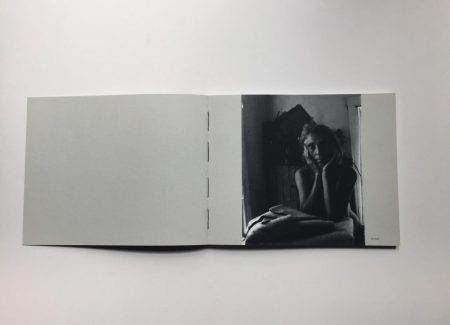

A blanket reappears in the following photograph. This time, it is thick and neatly folded, giving comfort to June’s elbows, which support the weight of her slightly forward-leaning body. It is a tender portrait of a beautiful woman. Her skin is tan, her eyes are closed, her face resting in the palms of her hands. A nude, I realize only at second glance, because her body, like her expression, speaks not through overt detail, but telling contours. It is among my favorite images of the book, not only for the soft lighting, but the essential connection to the space in which it was taken and to which it belongs . . . home.

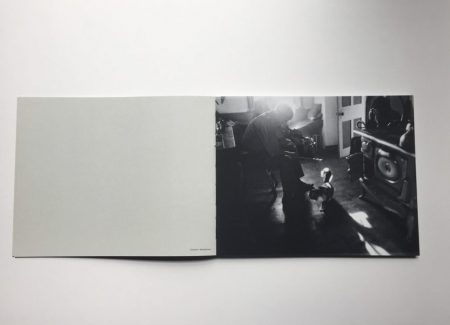

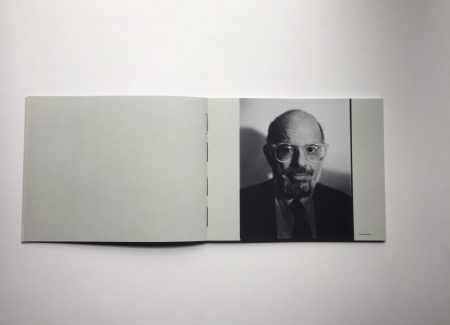

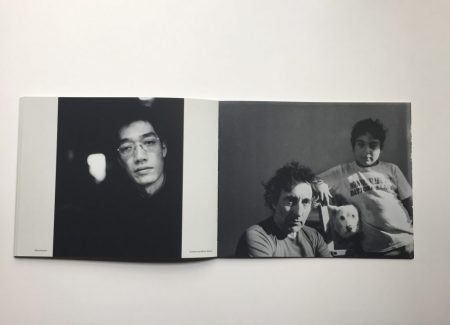

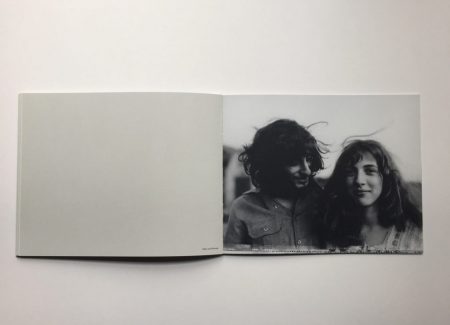

There are more portraits (and these are the only captioned images, providing the names of the people, as if to make sure that we know and remember), including an inquisitive looking Alan Ginsberg; Frank’s son Pablo, smittenly holding his girlfriend Rhonda, who smiles into the camera; and neighbors, such as John Angus Beaten who stands under a window, almost, but not quite surprised by the by the lens, holding a can of sardines.

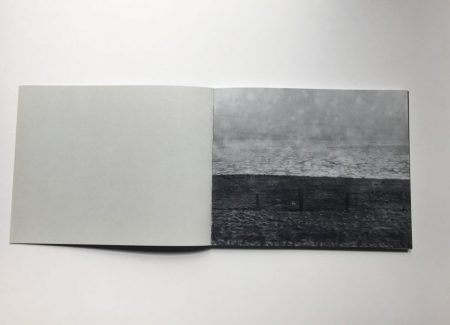

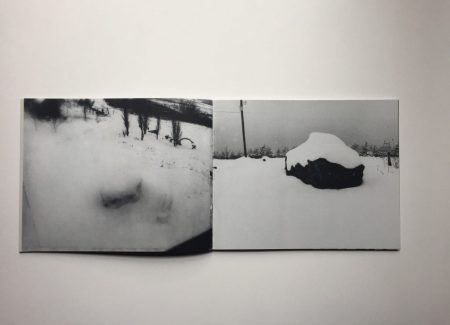

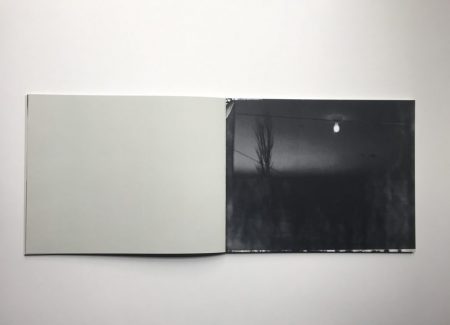

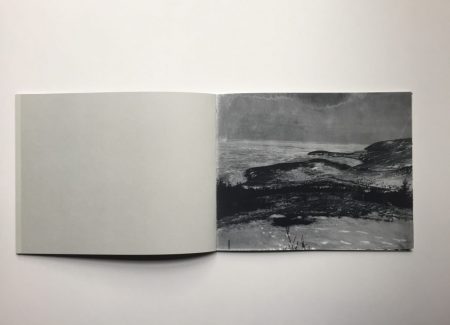

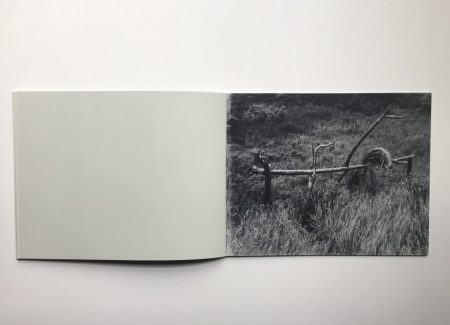

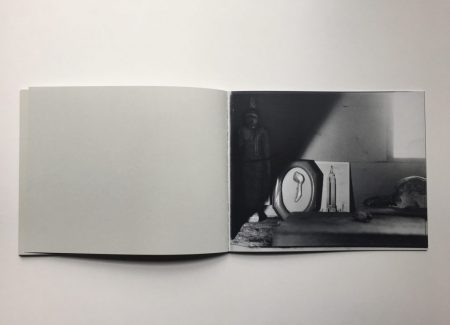

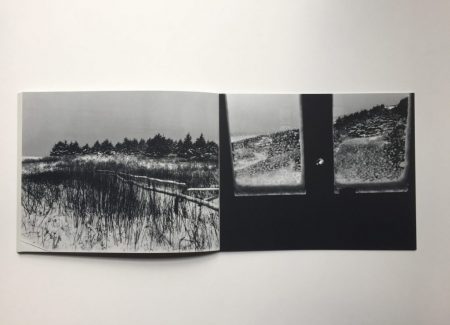

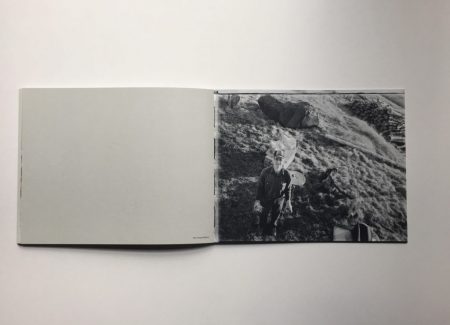

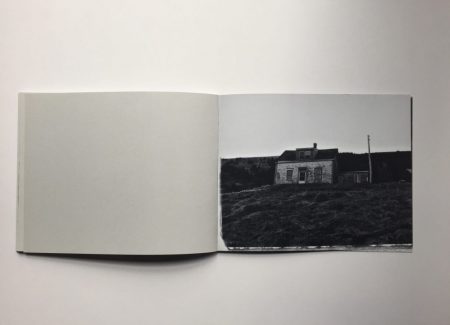

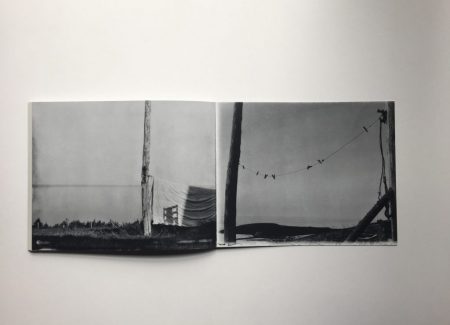

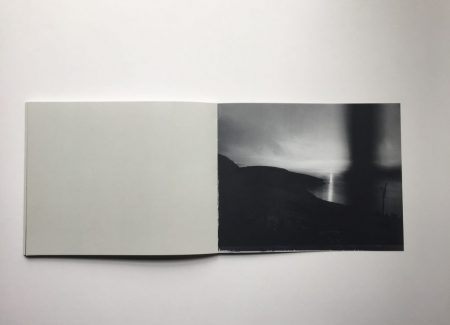

Other images include the well-known sceneries of the Mabou coast, with its rough hills and stubborn grasslands, its unpredictable sea furrowed by the ever-blowing wind, broken by patches of ice, then silent and still like a mirror. Often they are captured the way we know them: with Frank standing on an elevated point of view within the landscape; other times they are caught through windows and doors from within the wooden house. There are close-ups of rocks covered in snow, the totem sculptures that Frank installed around the property, as well as the famous poles and clothesline, yet without Frank’s images dangling from them. And although the sun every now and then appears, Good days Quiet feels like a winter-book, both as object and metaphor.

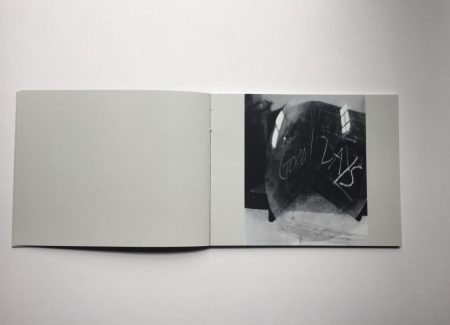

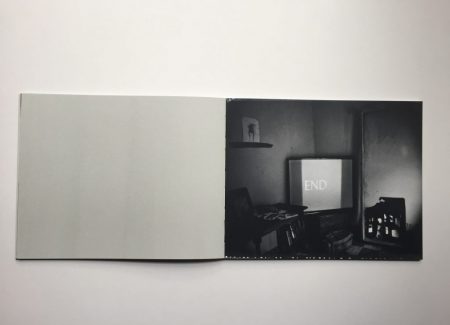

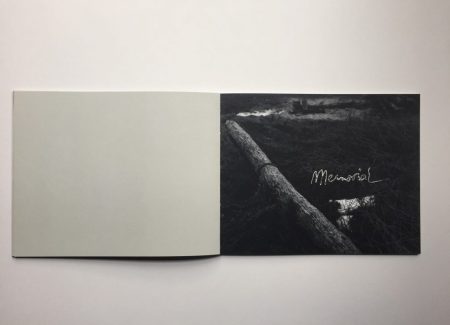

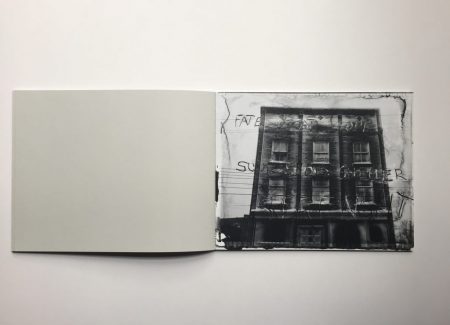

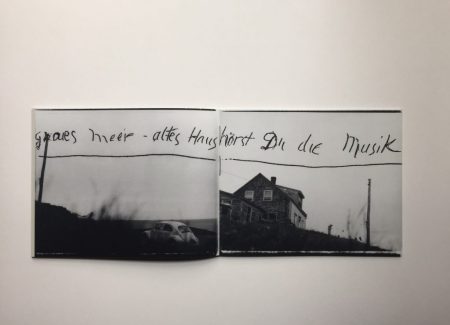

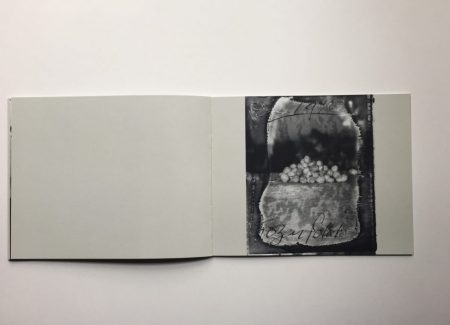

One, at times two, to a spread, the monochrome images are richly printed and textured, ranging from sumptuous blacks and moody greys, to gentle whites, and hues I have no name for. All of them clearly carry Frank’s aesthetic signature: tilted horizons and blurry edges, or the tactile surfaces with abstract patterns, the residues from pulling the Polaroid’s negative. ‘Surprises’ – as Frank has called them. But there is also a specific kind of sadness; or rather a sense of loss and melancholy. This feeling is particularly strong in those images that include Frank’s handwriting.

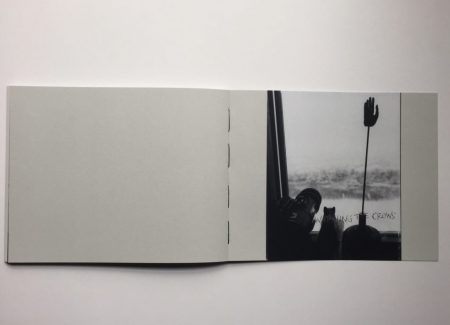

Sometimes descriptive, like in the delicate and slightly abstract photograph stating “Dec. 1980, Frozen Potatoes” – evocation ultimately inserts itself, such as in “Watching the crows” without any bird visible on the bright sky caught through a window, while a video camera, a wooden mouse or some other rodent, and the sculpture of a hand sit on the sill, as if giving their goodbyes. An image like a postcard left behind.

Good days Quiet is likely the last photobook that Frank compiled and edited himself. Therefore it seems pertinent to consider it an homage to the people and the place he loved and cared for. But this statement is too easy and incomplete. Looking at the book as whole, I find another answer. While much of its imagery has been included in Frank’s prior titles, Good days Quiet is neither repetitive nor derivative. It doesn’t continue his visual diaries (2010-2017), such as Park/Sleep or Partida, nor does it re-interpret The Lines of My Hands. More concentrated and precise than his later books, Good days Quiet appears more personal and open – it reads like a diary without narrative and unfolds as a series of impressions, loosely arranged and deeply felt. I think of it as a different kind of self-portrait.

This sentiment is echoed in the book’s design: the thick, concrete colored paper, the prints’ graphic quality, which emphasizes the Polaroids’ innate, yet deliberately applied photo-chemical ‘accidents’, the full-bleed images, as well as the lyrical sequencing defying any chronology. It is a simple book full of care for details. What appeals to me the most, however, is the open spine, revealing the binding threads and the glue that covers them – provoking a feeling that the photographer Anders Goldfarb put into words that I couldn’t find: “The poignancy of a maquette; of something hand-made; something that is given to you personally. Like a gift.”

In this sense, Good days Quiet closely relates to another maquette: Mary’s Book – Frank’s first attempt to connect photographs and words, melding the factual and personal, significance and meaning. And while Good days Quiet is less romantic and originates from an entirely different physical and emotional space – the raw tenderness, the mystery, and ambiguity remain.

On the book’s cover a weathered piece of fabric blocks the view from a window, reproducing the title in yellow, slightly washed-out letters. Below them, however, is another handwritten message. It says: memories from Robert. A vague hope, an intuition, perhaps gratitude.

Collector’s POV: Robert Frank is represented by Pace/MacGill Gallery in New York (here), with a number of other galleries also carrying secondary market inventory. Frank’s work is routinely available at auction, where recent prices have ranged between $5000 and $665000. Key images from The Americans consistently fetch five, and in some case six, figure prices.