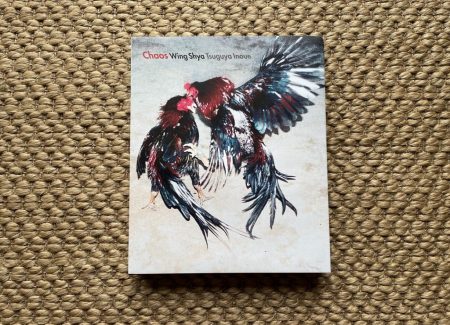

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2020 by Little More (distributor link here). Hardcover, 316×265 mm, 308 pages (unpaginated), with black-and-white and color image spreads/pairings. With short texts by the two artists in English and Japanese. Design by Tsuguya Inoue. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: While making a photobook is often a unique artistic collaboration between a photographer and a graphic designer, it’s a sad truth that the designer rarely gets much overt recognition for his or her contributions. In most cases, the designer (or team of designers) is listed in the colophon, essentially lost in the fine print, and in frustratingly too many instances, the designer isn’t credited at all. For those unfamiliar with the ins and outs of photobook publishing, photobooks seem to begin and end with photographers and their work, and the designers who create the experience of seeing those photographs in book form don’t seem particularly important. This fundamental misconception is one that needs correcting.

Photobooks like Chaos offer an intriguing first step in re-establishing some balance between photographer and designer. Yes, Chaos starts with photographs, thirty years of them in fact, from the Hong Kong-based photographer Wing Shya. But what’s altogether unusual is that Wing sent his massive archive (some 33000 images) to the Japanese graphic designer Tsuguya Inoue, and Inoue took on the task of selecting, sequencing, and presenting his own unique interpretation of Wing’s photographic career. Wing and Inoue are given equal status on the cover and on the spine, and the book very much feels like a joint effort. Even the cover image of cockfighting seems to echo the collaboration, pairing two powerful roosters in the midst of a battle.

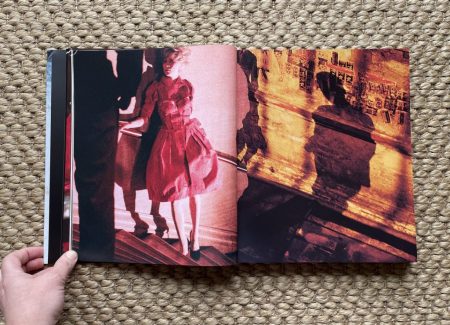

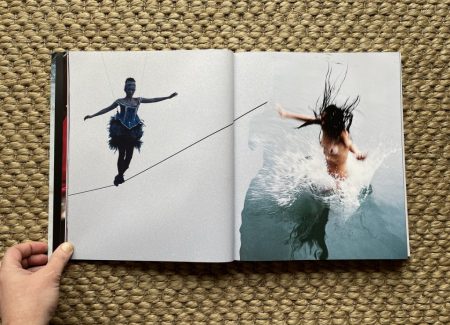

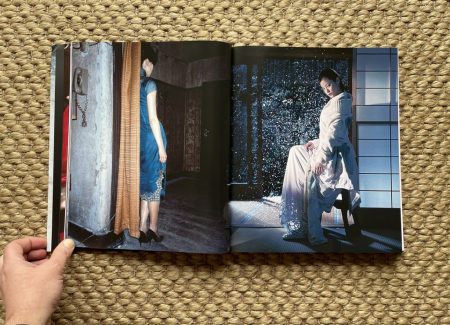

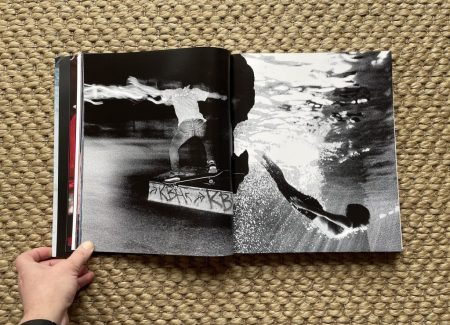

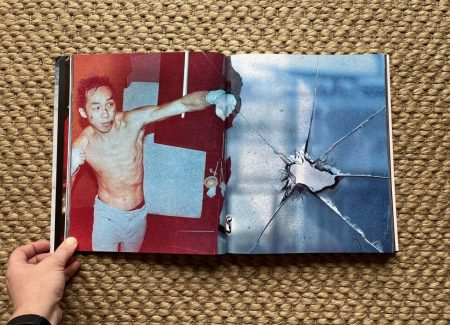

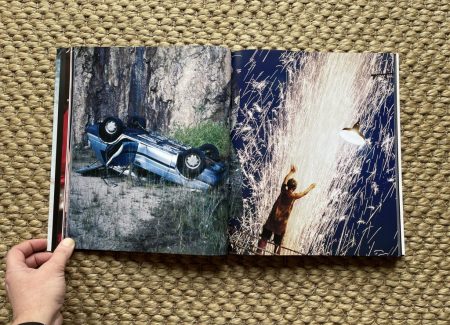

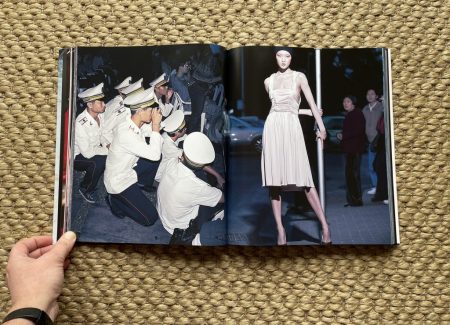

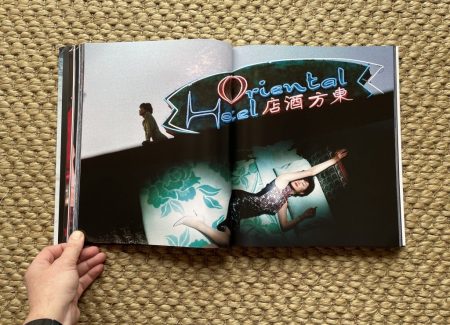

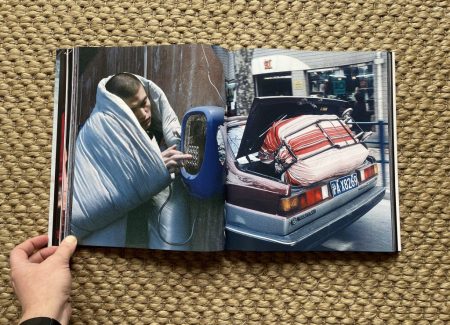

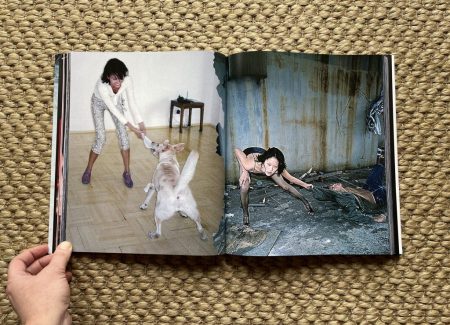

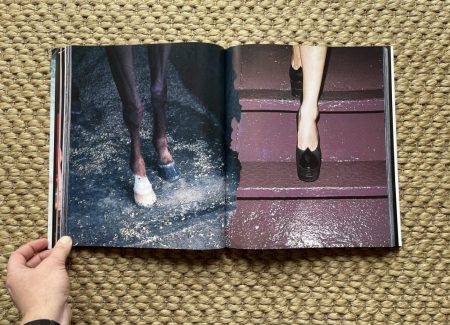

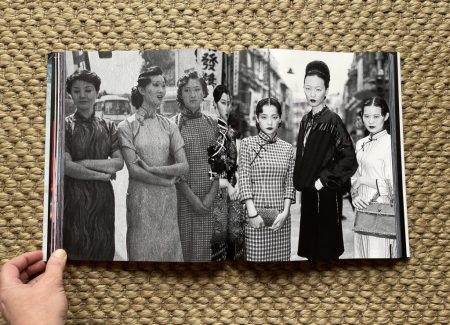

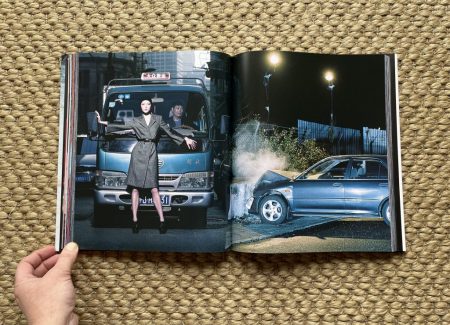

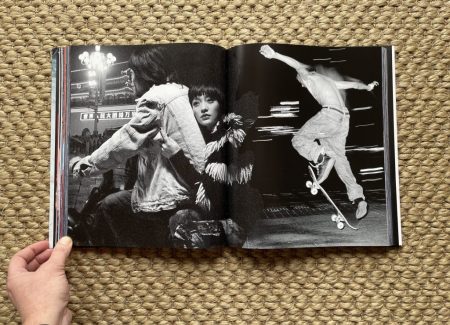

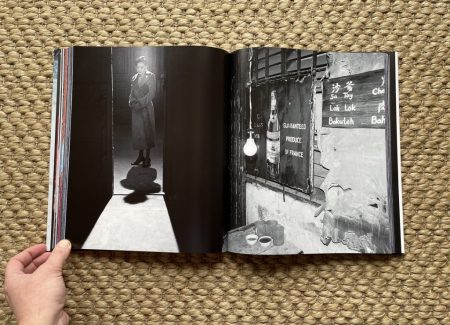

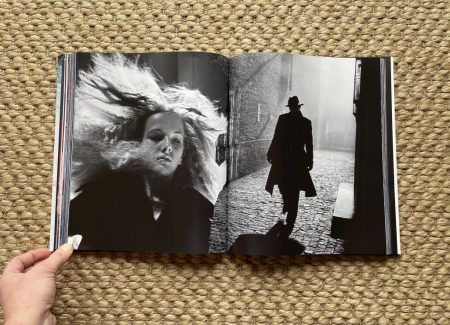

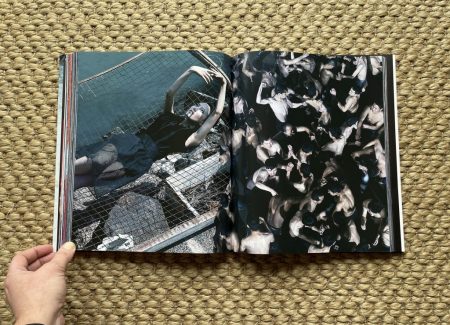

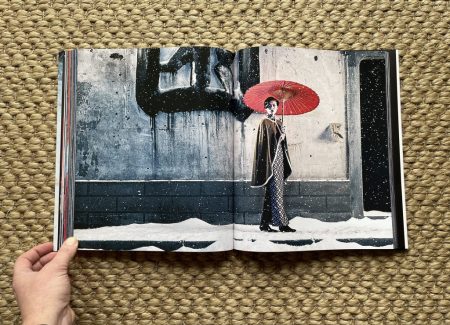

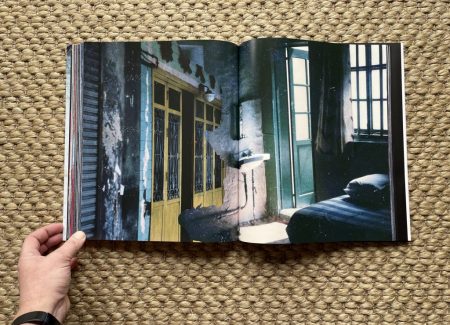

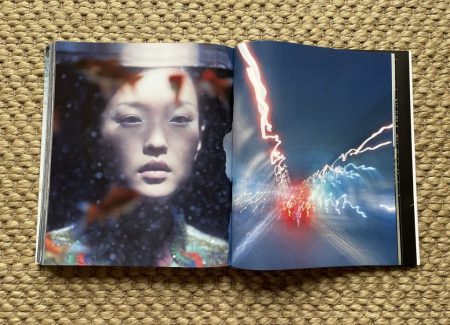

Inoue may be best recognized in the West for his poster designs for Comme des Garçons, but he has been working with major clients via his own design house Beans since the late 1970s, and has come to be particularly known for his integration of typography and photographic imagery. But his approach to Wing’s archive in Chaos doesn’t really include typography, aside from a few titles. Instead, Inoue has developed a visual structure that appears to draw its inspiration from torn paper collage. All of the spreads in Chaos are presented full bleed, and most feature paired photographs that have been combined via a jagged digital edge that essentially fuses the two images together. Often this “ripped” overlap occurs near the book’s gutter (for two left and right images fused vertically in the middle), and in a few cases, Inoue flips the axis and combines two wide images with a horizontal rip. Aside from a few full spread images, the entire monograph is made up of these hijacked pairings, often shuffling together images from different parts of Wing’s career.

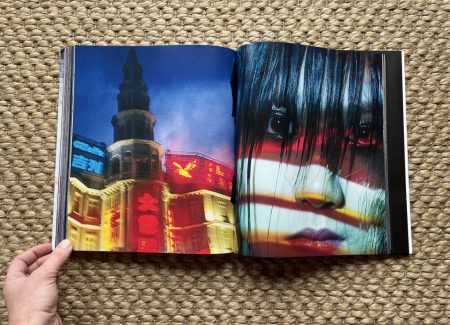

Wing Shya first made his name as a photographer in the 1990s, when the acclaimed film director Wong Kar-Wai hired him to be the set photographer for Happy Together. Wing would go on to shoot stills for a number of Wong’s films over the next decade, including In the Mood for Love, Eros, and Acting Out. Wing then branched out into fashion and other commercial work, in addition to continuing to shoot more casually in the vibrant streets of Hong Kong. The result is a broad body of work that leverages the moods and colors of Wong’s aesthetic, and extends those themes into even more stylized setups and dream-like moments, seen against the backdrop of the energetic city.

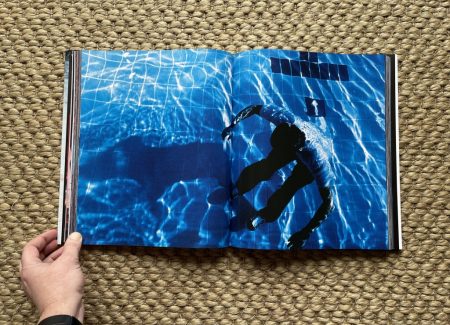

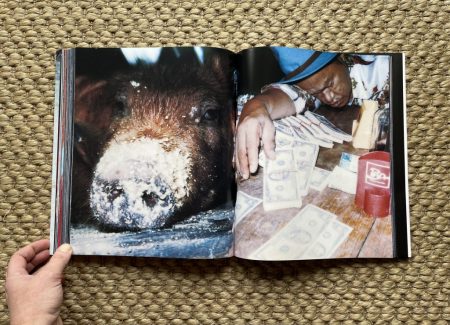

The majority of Inoue’s pairings uncover formal echoes between Wing’s photographs, from the straightforward to the wildly unexpected. He shows us the visual similarities between horse hooves and a woman’s high heeled feet, spiky long grasses and sparkling fireworks, hanging laundry and children linked together in preschool, and a passed out man surrounded by money and a pig’s snout covered with sticky grain. In some cases, he finds an unmistakable visual repetition – between a man’s puffy hair and a cat’s ears, an acrobat and a woman jumping into water, or one woman tugging a dog while another pulls a man by his hoodie – while in others, his connections are more subtle and ethereal, like his mashups of angled arms and a forest ridgeline or legs in water and misty hills. While obvious links are found here and there – a boy in a hole paired with prisoners buried up to their necks, or a kid’s puny muscles and a man flexing behind a model – the formal resonances between a lying figure and the Star ferry, or a jumping man on a skateboard and a diver (both dragging along trails of light), feel more inspired and unpredictable.

Less literal are many of Inoue’s pairings that turn on similarities of color or mood. Blue lily pads invade a tender scene in a swimming pool, cast shadows link setups in soft pink and shimmering yellow orange, muted shades of yellow and green linger in empty rooms, and an atmosphere of sensual cool links a woman applying her lipstick and a man lighting a cigarette. Wing often uses Hong Kong’s ubiquitous neon signs as a way to play with saturated color, and Inoue finds echoes between a green bedroom scene and a woman standing beside a rooftop neon sign, colored stripes across a woman’s face and another neon-lit night view, and the watery reflections down an alley and neon palm trees in primary colors. More subdued choices see parallels between squashed paint tubes and carp in a pond, a pink painted palace wall and disembodied mannequin legs, and black leather gloves typing on a keyboard topped by a nude on a black leather couch.

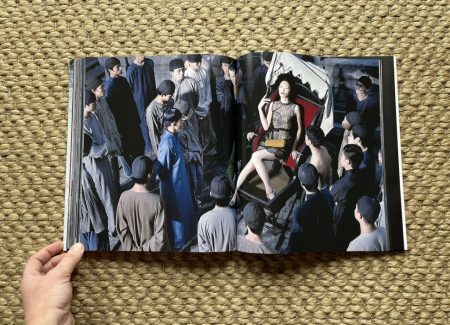

Another technique Inoue employs to match photographs is creating hybrid scenes, where action appears to flow from one Wing image to another. A boxing punch results in broken glass, sparks fly when statues kiss, a woman takes a superhero jump over the city, and a stripper dances for rows of empty theater seats, each scene made up of the overlap of entirely separate photographs. This approach takes a surreal turn when Inoue matches a man’s body and a woman’s outstretched legs, and he even brings in a film-making reference, with a blast of white coming out from the lens of a movie camera.

It’s clear that Inoue took this design assignment as an opportunity to experiment, and other spreads find him playing with additional ways to make two images talk to each other. Several place two unrelated heads as if in dialogue, or pairs the heads based on similarities in eyes, head shape, or other defining characteristics. He partners the painted faces of models and clowns, the grim visages of a bruised face and a deadpan model, the weathered brown of a man and a horse, and the elemental roundness of a Buddha statue and a young boy. In still other compositions, he layers two versions or variants of the same scene together, creating stuttering time-sliced hybrids of legs bent on a sofa, a man draped over a car bumper, a dancer in a blue kimono, and a woman with strangely oversized plastic lips.

If this photobook had simply been a standard career-spanning monograph of Wing’s work, we might have spent more time thinking through how he brought his own eye to framing Wong Kar-Wai’s movie sets, how Wing’s fashion aesthetic has evolved over time, or how Hong Kong provides a unique backdrop for Wing’s imagery. But Chaos doesn’t really encourage this kind of single image or even career arc analysis. Instead, it asks us to step back an watch one artist interpret another, with Wing’s photographs becoming the visual raw material that is then housed in the structure of Inoue’s design.

Inoue’s choices of ordering, filtering, and contextualization transform Wing’s photographs, offering something akin to a stream of consciousness flood, where visual harmonies and relationships knit the large mass into something that has the potential for playfulness and surprise. As seen in Chaos, Wing’s photographic eye was already inventive and lively; when redirected through the prism of Inoue’s mind, those same pictures feel more structured in terms of form, color, and composition, but also more open to risk and uncertainty. In short, the insertion of Inoue’s vantage point forces us to see Wing’s pictures differently than we might have. We’re entirely used to having curators and historians remix the work of famous and not-so-famous photographers in search of new insights. Chaos is notable proof that we should be giving more graphic designers the same chance.

Collector’s POV: Wing Shya does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. As a result, interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artist via his website (linked in the sidebar).