JTF (just the facts): A paired show between the two artists, on view in the two room gallery space behind the bookstore. (Installation shots below.)

The following works have been included in the show:

Sally Mann

- 18 tintypes (collodion wet-plate positive on anodized aluminum with sandarac finish), 2020, sized roughly 21×19 inches, unique

- 8 platinum/palladium prints, 2022, sized roughly 13×15 inches, in editions of 3+1AP

Edmund de Waal

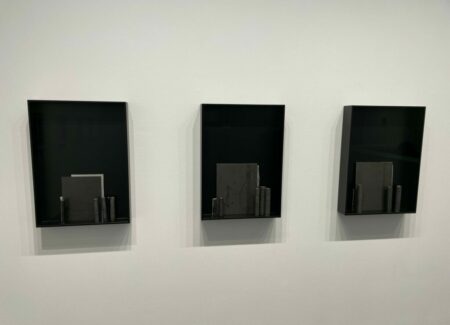

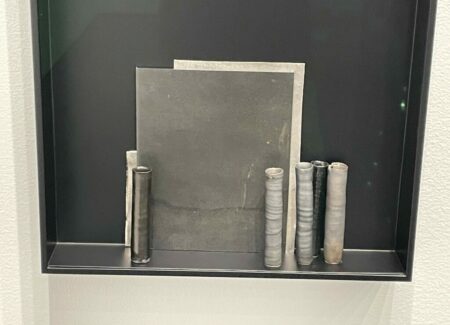

- 3 porcelain, Cor-Ten steel, platinum, aluminum, and glass, 2023, sized roughly 28x20x4 inches, unique

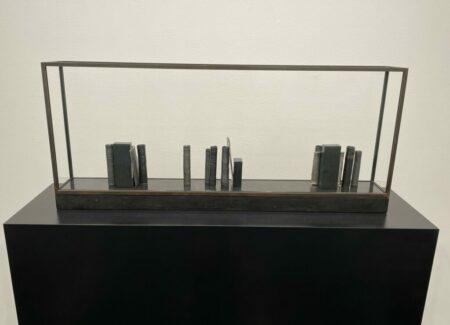

- 1 porcelain, Cor-Ten steel, platinum, aluminum, and glass, 2022, sized roughly 21x7x7 inches, unique

- 1 porcelain, Cor-Ten steel, platinum, marble, steel, and plexiglass, 2022, sized roughly 21x10x4 inches, unique

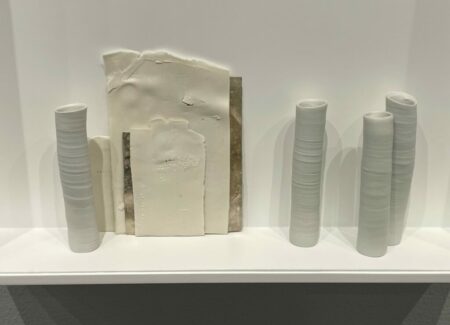

- 1 porcelain, marble, platinum, steel, and plexiglass, 2022, sized roughly 23x16x6 inches, unique

- 5 porcelain, silver, aluminum, and glass, 2023, sized roughly 15x20x4 inches, unique

- 1 porcelain, marble, platinum, steel, and plexiglass, 2022, sized roughly 20x46x6 inches, unique

A catalog of this paired show has been published by the gallery (here). (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: When putting together a gallery or museum exhibit (or even an art fair booth) that pairs the work of two artists, the easiest path forward is to use similarity as the structural bridge. And so we see plenty of straightforward pairings of artists working in the same medium, from the same geography or time period, with matching personal characteristics, using related techniques or exploring common subject matter. But more intriguing curatorial pairings often come from riskier combinations, where the link between the two artists is more tenuous (and less obvious), but the resonances between the disparate artistic approaches somehow come together in unexpected context-jumping harmony. When this magic happens, both bodies of work feel surprisingly enriched by the proximity, as the physical juxtaposition forces us see each artist’s contributions in ways we hadn’t considered before.

This show pairs the sculptural ceramics/installations of Edmund de Waal and the photographs of Sally Mann, and while both artists are represented by Gagosian, the connection between the two isn’t entirely apparent, at least initially. The relationship between the two artists began in 2010 when Cy Twombly (a friend of Mann’s) gave her a copy of de Waal’s family memoir The Hare with Amber Eyes. After Twombly died, Mann made a series of photographs of Twombly’s studio (reviewed here, in 2016), and at that time, de Waal had a conversation with Mann about the pictures, which appeared in the accompanying catalog. In the years since, they have continued to exchange ideas, now resulting in a more formal pairing of recent works.

Mann brings two projects to this exchange, a set of tintypes (made in 2020) and a group of platinum/palladium prints (made in 2022). The tintypes are decently large, at least in comparison to what we might expect from 19th century examples using the same process, and are universally dark and moody. Out of the deep shadows and dark chemical washes emerge hints of small still lifes, but even up close, accurate identification of the subjects is extremely difficult. Might that be a pair of lemons, some rusty tools, some railroad ties perched on a can, a flask and some bottles, a stone vase or urn, or some wooden hangers? It’s hard to be sure, but of course, specificity isn’t what matters here.

These formal studies have been allowed (or even encouraged) to drop into poetic mystery. In many ways, they are exercises in exploring the subdued possibilities of lines, textures, surfaces, and edges, but the thick, rich darkness of Mann’s chosen palette turns these characteristics into something even more ephemeral and diffuse, where representation dissolves into near abstraction. Mann pushes tonal variations and process quirks into ghosts, fogs, and echoes, where hints of shine and highlight draw attention to curves and gestural edges, each composition more of a whisper rather than a direct visual dialogue.

In her platinum/palladium prints, Mann opts for a much lighter atmosphere, where ethereal nuances of whites and off-whites are the defining values. The works ostensibly document gravestone fragments found at a stonemason’s workshop near her Virginia home and brought into her studio, but the images drift into indistinct fuzziness, with weathered edges and craggy blocks offering all the subject matter necessary for Mann’s meditations. A few slabs with faint inscriptions help orient us, but largely the worn rock is featureless, which Mann then softens further with fleeting glimpses of dirty textures, rounded facets, and cast shadows. What is left behind is a sense of mute (or silenced) presence, the specific personal histories these stones once commemorated now forgotten or withheld. In both the tintypes and the platinum/palladium prints, Mann amplifies the possibilities of her modest subject matter via the expressiveness of her photographic processes, the imperfections and chance elements of the pictures heightening their sense of ambiguity and obscurity.

Edmund de Waal’s recent sculptural assemblages wrestle with many of the same aesthetic concerns as Mann’s photographs, albeit in three dimensions instead of two. De Waal’s works are shown in two forms – as hanging wall objects, where small porcelains and other collected items are housed in deep frames that act like a shelf with a flat back, and as stand-alone sculptural arrangements enclosed in glass vitrines. In contrast to the ephemerality of Mann’s photographic moments, de Waal’s works have an immediate physicality and spatial presence, which is then minutely modified by shifting light conditions in the gallery.

In both black/grey and white palettes, de Waal gathers arrangements of upright tubes, flat plates/sheets, and blocks, each arrangement composed with precise attention to subtleties of visual balance and rhythm. But it is his rich tactile surfaces that give these works their life. The tubes have rolled and ribbed striations, and are covered with glossy glazes in a range of gloriously subtle tones; the sheets are variously shiny and metallic, dull and mottled, crackled and veined (when marble), and other opaque versions of creamy ceramic; and the steel boxes are harder edged and unforgiving. When combined together, de Waal’s sophisticated assemblages play with round/flat/square proportions, ranges (and opposites) of surface texture, and patterns of short/tall, thick/thin, and in front/behind, each work an expressive iteration within defined constraints.

When the works of these two artists are interleaved together as they are here, the affinities between their artistic worldviews become readily visible. The links between still life setups, monochrome palettes, elemental geometries, and textural richness emerge first, setting up easy back-and-forth comparisons. I found myself wanting to temporarily apply one artist’s approach to the works of the other – what would de Waal’s arrangements look like if seen in gradations of lush moody shadow and flattened (and cropped) by the eye of the camera? And what would Mann’s setups feel like in three dimensions, where the dynamism of movement and shifting light could activate the objects and create extended experiences instead of single instants? Both artists’s work ultimately felt more complex and layered because of this dialogue, the combined narrative embellished by the interplay of photographic and sculptural seeing.

It’s also clear that both Mann and de Waal are motivated by a sense of the poetic, both in the literal sense of some of their inspirations and allusions, and in the more amorphous ways they make artistic decisions and create moods. Each actively embraces the physicality of their respective materials, and allows the lack of control inherent in their processes to become integral to the resulting works; in this way, inadvertent flaws become expressively improvisational features and unexpectedly inspired forks in the artistic road. In both cases, a quietly rich humanity infuses the work, even when the compositions have been reduced to the most elemental of forms.

Collector’s POV: Sally Mann’s photographs in this show are priced at $30000 each for the tintypes, and $13500 each for the platinum/palladium prints. Her photographs are widely available in the secondary markets, with recent prices generally ranging between $3000 and $260000.

I can’t believe Edmund de Waal has paired himself up with that total phony Sally Mann