JTF (just the facts): A total of 102 black-and-white and color photographs, alternately framed in light wood and matted or framed in black and unmatted, and hung against white walls in the main gallery space and the entry area.

The following works are included in the show:

- 100 gelatin silver prints, 1993-2000, each sized roughly 14×11 inches, in editions of 12+3AP

- 2 Ilfochrome prints mounted on acrylic, 1996, each sized roughly 47×37 inches, in editions of 10

(Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: In an early 21st century cultural moment where the broader acceptance of the nuances of gender fluidity is on the rise, our collective interest in rediscovering (and re-understanding) the work of the Japanese photographer Yasumasa Morimura should be similarly increasing. Morimura was and is, of course, a pioneer of performative self-portraiture, particularly in the ways that as a Japanese man he has successfully taken on the glamorous personas of so many famous women.

But as we think about where Morimura fits in the arc of photographic history, the narrative around his work seems firmly entrenched and relatively narrow; we know that he has insightfully probed the nature of identity, the seductions of celebrity, and the complexities of sexuality, and yet, we seem to have reduced his accomplishments to that of an accomplished playactor or impersonator, whose story is always essentially the same (but in a different costume) and whose mask can inherently only fit so well.

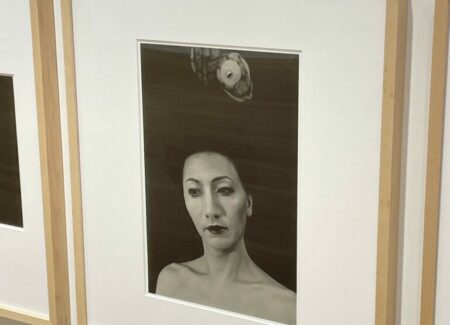

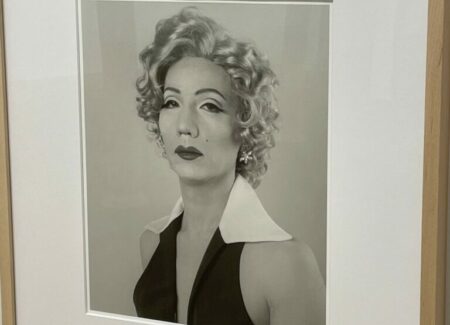

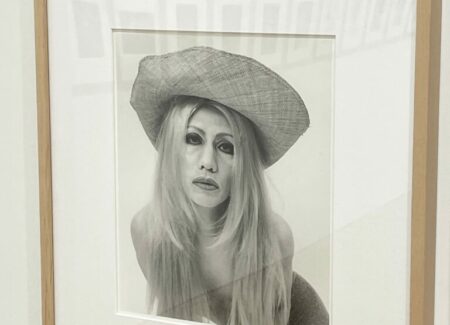

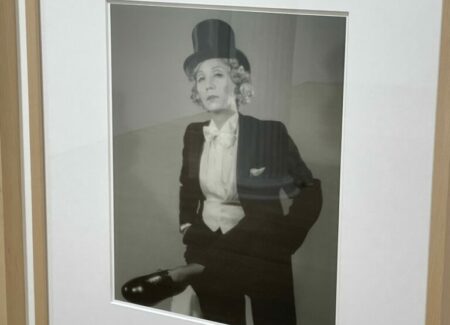

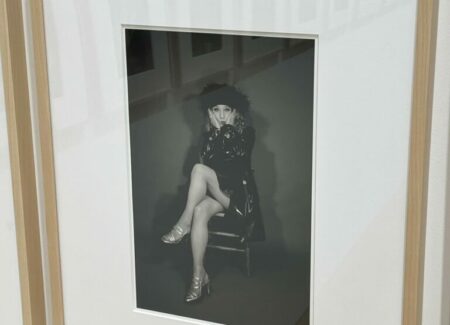

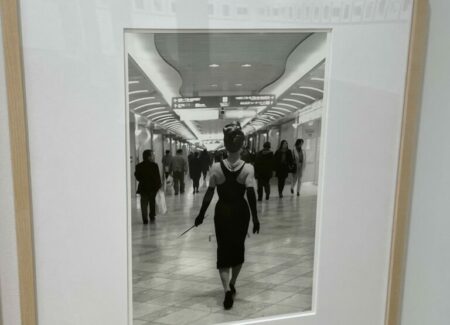

In this way, there will be some who will see exactly what they expect to see in this rehanging of Morimura’s knockout black-and-white self-portraiture project from the late 1990s, and who will likely be drawn in by the name game that can be played by trying to figure out who Morimura is emulating in any given picture. And I’ll admit, that in my first few minutes in the gallery, I too was quick to test my identification skills, ticking off Morimura’s personifications of Marilyn Monroe, Audrey Hepburn, and Brigitte Bardot with some ease, and struggling a bit more with Marlene Dietrich, Greta Garbo, Ingrid Bergman, Elizabeth Taylor, Liza Minelli, and other starlets from Hollywood’s golden age. Also mixed in to the project are a few homages to relevant artists and photographic artworks, from Man Ray to Andy Warhol, which can again be checked off with some sense of accomplishment.

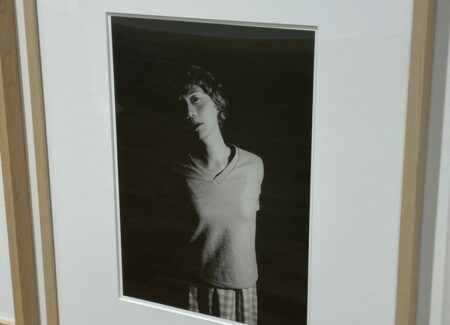

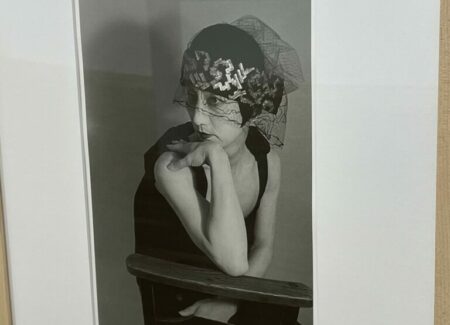

But this kind of around-the-room identification only goes so far, especially when not all of us are old Hollywood experts enough to place the specific allusion or reference Morimura is making in any given picture. And it was in this spot that I started to see Morimura’s photographic art a bit differently – when we know who Morimura is inhabiting, we naturally test the fidelity of his performance against what we can remember about the original (and her often strikingly unique persona or presence). Morimura’s craftsmanship is consistently superlative, so often the singular friction, dissonance, or hollowness we observe is that of a male portraying a female (and in particular, a Japanese male portraying a Western female.) But when we don’t immediately know the person Morimura is mimicking, something different occurs – we’re not entranced and impressed by a famous visage being recreated, but instead see Morimura more clearly, trying on alternate possibilities for himself. In a sense, in the quieter faces and poses we can’t place, we can feel Morimura better, and can pay closer attention to the tiny emotive details he has mastered to create each and every one of these looks.

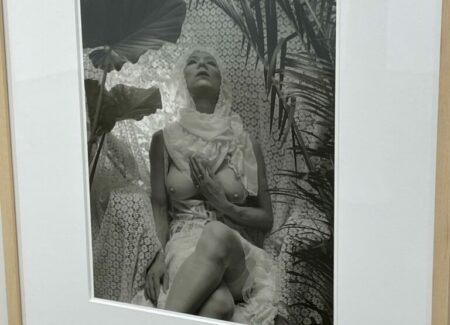

Some of Morimura’s most powerful works deliberately avoid a straight on portrait and use skew and steep camera angles (particularly from above and below) to isolate a moment of reflection, contemplation, or expressive engagement, in some cases with flares of light set behind to cast warm highlights. His face is almost never a smile; sometimes it’s a deliberately vacant stare, but most often Morimura reaches for a deeper kind of interaction that feels consistently inward and introspective, like he is seeing (and constructing) a version of himself from outside his own body.

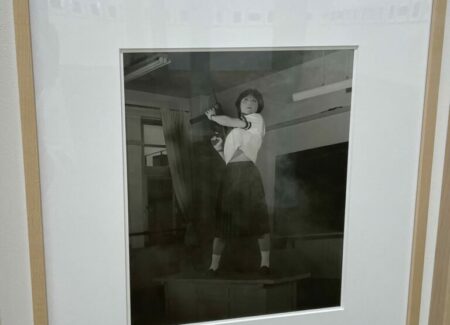

More elaborate scenes get beyond facial posing and find him lounging among bedroom sheets, smoking cigarettes, strutting through the subway, and provocatively twisting in a bubble bath. He tries on kittenish poses, leggy looks in a bra and panties, and overt role playing in a nurse’s uniform or a kimono. Compositionally, he sees himself through a wineglass, organizes a reflected scene in a dressing room mirror with flanking lights, and variously brandishes a machine gun. In looking at picture after picture in this long series, it becomes clear that Morimura does so much with so little – a splash of messy hair, the turn of a shoulder, a dramatic look upward, or a swirl of headscarf is all he needs to create an alternate identity.

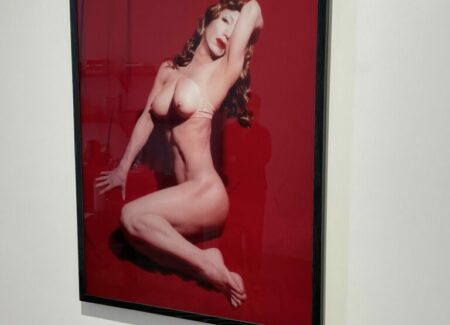

A couple of larger scale color images hung in the entry area offer a reminder that Morimura has often of late opted for more elaborate staging and complex costumes and props, the theatricality of these set pieces overwhelming the pared down intimacy that he regularly found in his smaller black-and-white works. The bigger color works are impressive in their own way, but can also feel so controlled and manicured that there isn’t much room for Morimura to interject himself. The black-and-white portraits feel more loosely improvisational and authentic (of course they are neither), but they offer us more personal entry points as viewers; with an elaborately triumphant Morimura as Elizabeth Taylor (wearing a towering gold headpiece), there is really only one plausible reaction – an acknowledging head nod to Morimura’s astonishing dedication to performative drama.

This smart show felt like an invitation to re-see Morimura at his most elemental – stripped down and unplugged, rather than with his full band. The works on view stand up to that renewed scrutiny well, taking us back to the first principles that have provided the essential foundation for his long and deservedly renowned artistic career.

Collector’s POV: The black-and-white prints in this show are individually priced between $2500 and $4000, depending on the place in the edition. The color prints are priced at $25000 each. Morimura’s prints have been intermittently available in the secondary markets in the past decade, with prices ranging from roughly $2000 to $66000.