JTF (just the facts): A total of 24 photographic works, hung unframed against white walls in the main gallery space and the entry area. All of the works are digital archival pigment prints, originally executed as diazotypes in 1973 and reprinted as facsimiles in 2023. Each is sized 22×17 inches, and is available in an edition of 3+1AP.

The show also includes 3 sculptures, arranged in the center of the main gallery. Each is handwoven sisal and chair, from 1972; the works are sized 35x25x25, 42x24x24, and 35x85x85 inches, and are unique. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: Over the past decade, Bortolami Gallery has done an exemplary job of consistently presenting the photographic work of Barbara Kasten. In gallery shows in 2022 (reviewed here), 2019 (reviewed here), 2017 (reviewed here), 2015 (reviewed here), and back even further, and supported by a 2015 retrospective at the ICA in Philadelphia and inclusion at various art fairs, the gallery has thoughtfully shown us the range of Kasten’s output across five decades of art making. This show continues to methodically fill in the larger arc of her career, jumping back to her very early days and a show she had in 1973 at the California College of Arts and Crafts.

Back in the early 1970s, Kasten was exploring the link between painting and textiles, in her graduate work in weaving at the CCAC and then during a fellowship with Magdalena Abakanowicz in Poland in 1972. While there, she experimented with hand-dyed sisal weavings, which she wrapped around simple bentwood chairs to create draped, bulged, and sinuously sculptural forms. Her textiles reimagined the underlying architecture of the chairs, making them feel more like distorted or amplified bodies, with exaggerated folds and undulations that resembled hips, buttocks, torsos, and breasts. Kasten then returned to California in 1973, and paired an installation of these colorful sculptures with a series of photographic diazotypes, where she posed a nude female model on a similar chair in a variety of formal arrangements. This exhibit conceptually reprises that 1973 show at CCAC, albeit with fewer sculptures and facsimiles of the original blue diazotypes.

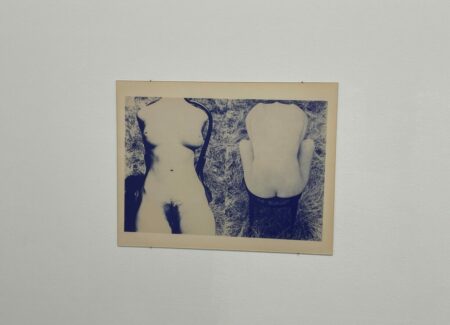

Given that the sculptures were made before the photographs, an artistic translation from the roundness of three dimensions back to the flatness of two is taking place, with tactile and physical characteristics being reduced back to pared down visuals. In the photographs, Kasten takes the elements of chair, body (we never actually see a face), and surrounding grass and systematically and iteratively rearranges them. Her matter-of-fact gaze turns the body into anonymous sculpture, but her eye is also undeniably feminist; it is a female gaze that appreciates how the simple wooden structure of the chair can represent the roles and conformities imposed on women by society, and how a woman is forced to contort her body (and her self) to fit into those limitations.

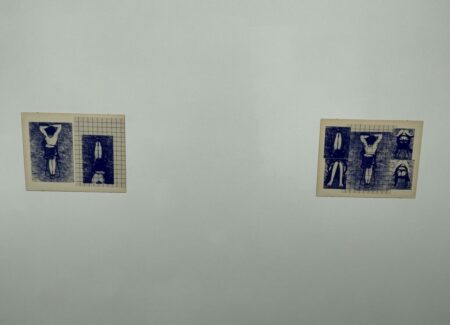

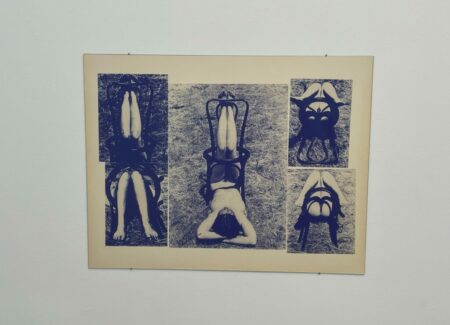

There actually aren’t that many ways to sit in an armless chair like the one Kasten was using, but her pictures document plenty of possible configurations of body and chair, at least the ones that have some sense of symmetry or balance. Of course, the model sits on the chair facing forwards with her arms held behind, and then turns around facing backwards straddling the chair. Various poses twisting, draping, shifting, leaning, and tucking legs up make appearances, as do flipped setups with the model’s knees upside down and back. In a few arrangements, Kasten has removed the seat of the chair, creating more provocative see through options for buttocks and crotches, especially when the chair is laid down on the ground and legs end up in the air. Many seated poses play with butterfly legs and arms, alternately pulling and spreading, with heads down or up, creating mirrored patterns of legs and arms. There’s even one pose with the model precariously perching on the back of the chair, which is then followed by a complex setup of the model’s legs inverted and pushed through the chair (both the seat and the back), like a thread through a needle, creating yet another set of formal interactions between her limbs and curves and the structure of the chair itself. Seen in the context of the woven sculptures nearby, the photographs seem to merge the chair and body into hybrid configurations; instead of a woman on a chair, they are transformed into an integrated, almost inseparable combination of the two, where the positional ideas of above, below, on, under, and through are reoriented in intertwined formal experiments.

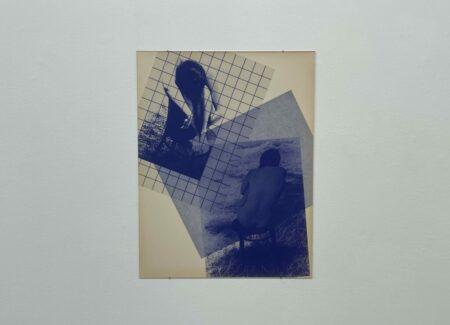

Photographically, Kasten’s toolbox only held a handful of techniques, which she then remixed in different combinations. She had standard exposures and their negatives, giving her light and dark inversions, and she added tinted squares (of soft light blue) and dark blue gridlines, which she layered on top of the photographs. Each print was an arrangement of photographs and interventions, with the images variously resized and reoriented, and placed in singles, pairs, triplets, and small groups of as many as five images.

As shown on the walls here, the prints feel meticulously iterative, with Kasten working through ideas in sequences and series. Three seated nudes are shown in a light-dark (inverted)-light configuration, and then that same triptych is then further embellished by squares of gridlines and tints on the light figures. Pairs of knees are seen dark (inverted)-light pairings, and then flipped, with another tinted square added in. Kasten actively plays with contrasts, reversals, mirroring, the appearance of “measuring” or “blocking” with the woven gridlines and “veiling” or “covering” with the tinted squares, and ultimately allows the formality of the arrangement of the prints themselves to loosen up and wander into more overlapped groups and collage-like gatherings. As she does so, the structure of the artworks seems to become more and more malleable and open-ended, her visual layerings (and their symbolic implications) evolving toward more complex impressions.

Kasten’s early works are likely under known in the context of early 1970s feminist photography, but they deserve to be better appreciated. These works also offer the aesthetic seeds of Kasten’s eventual move toward precisely seen abstraction and geometric arrangement, as well as her embrace of lesser known photographic techniques like the cyanotype and diazotype. While there is an inherent formal simplicity to these photographs, the images resonate with much more conceptual crackle and power than most contemporary studio-based nudes that play with similar bodies and arrangements – Kasten’s incisiveness in building up a visual vocabulary was apparent from the very beginning of her career. For many that think they know Kasten’s work well, these early pieces will be an altogether surprising discovery, but one that feels unexpectedly aligned with and supportive of what came later.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced at $5000 each, or at $100000 for the full set of 24 prints. Kasten’s photographs have been sporadically available in the secondary markets in the past decade, with only a few lots coming up for sale in any given year. Prices for those sales (which are likely not representative of market for her best work) have ranged between roughly $1000 and $12000.