JTF (just the facts): A total of 16 black-and-white and color photographs, framed in silver metal and unmatted, and hung against white walls in the front gallery space, the smaller middle gallery, and the office area.

The following works are included in the show:

- 3 digital silver gelatin prints, 2023, sized 39×26 inches, in editions of 5+2AP

- 6 digital silver gelatin prints, 2023, sized 27×18 inches, in editions of 5+2AP

- 6 digital silver gelatin prints, 2023, sized 20×16 inches (or the reverse), in editions of 5+2AP

- 1 archival pigment print, 2023, sized 20×16 inches, in an edition of 5+2AP

- 3 mixed media, 2023, sized roughly 88x70x3 inches, unique

(Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: For the Bronx-born photographer Elle Pérez, their Puerto Rican heritage and diasporic identity, and a broader effort to sensitively document underrepresented people and places, have been consistent undercurrents in the early evolution of their work. Their newest images have been gathered together under the title guabancex, who was the goddess of storms for the indigenous Taino peoples of Puerto Rico and elsewhere in the Caribbean, and variously associated with weather, spiraling winds, hurricanes, chaos, and destruction. As a kind of muse, the spirit of guabancex hovers over this project (and its presentation as a gallery show), becoming momentarily visible in literal floodwaters and translucent plastic sheeting, and more symbolically present in an ongoing struggle between light and dark.

Pérez’s previous gallery show in 2018 (reviewed here) was a subtle examination of selves and identities, as seen in portraits and images of bodies exploring (and celebrating) the fluidity of gender; the pictures were tender, intimate, and in some cases private, but not without a rumble of expectant tension. In this new body of work, Pérez largely steps back from that concentrated human engagement, turning their attention to the contours and moods of anonymous spaces, both natural and man-made.

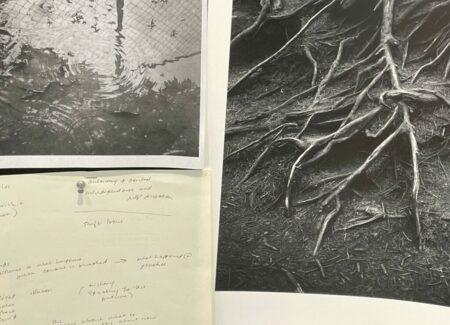

Several images use flooding (presumably in Puerto Rico) as a compositional element, with watery reflections, seepages, and shiny surfaces activating what might otherwise be mundane observations. In one photograph, the water rises over the curb to meet the angled line of a chain link fence; in another, a look down at a flooded area is decorated with the dark reflections of nearby trees and plants overhead, as well as the pattern of the fence again; and in a third, lazy droplets interrupt the flat reflecting surface of the floodwaters which have overrun a walled in area. In each case, Pérez makes sophisticated compositional use of the available tonalities and reflections, using layering and doubling to enrich the complex visual confusion.

A second group of photographs dives deeper into the swamplands, where the roots of the mangrove trees meet the still water and the lush undergrowth dapples the light. Pérez controls the interplay of light and dark in these shadowy areas with suppleness, transforming the lines of the roots into thick gestural marks which then cast shadows that densely mottle nearby natural surfaces, to the point of near abstraction. They apply a similar aesthetic in an image of a textural cave wall, the craggy darkness seeming to dissolve into approximation.

In many of the strongest images in this show, Pérez pushes the tonalities until they verge on atmosphere, in an almost Minor White style vision of the psychological possibilities of photographic uncertainty. In two photographs of a dining shed at night, what looks like translucent plastic sheeting covers the windows, allowing filtered light to shimmer out of the darkness. One work features a drift of sparkling highlights, the drapery appearing almost like waves or seductive watery contours, while the other is somewhat more recognizable, with silhouetted plant forms seen in front of the misty window-like screening. Pérez is similarly successful with the undulating ripple of plastic in a park trash can, where thin criss crossed shadows give the bag a tactile vegetal quality. When they return to more overtly urban subject matter on the subway, Pérez adapts this mysterious aesthetic to the machined surfaces, catching a fleeting glimpse of overhead lights reflected in a window and trying to decipher the message communicated by a fogged snippet of erased graffiti.

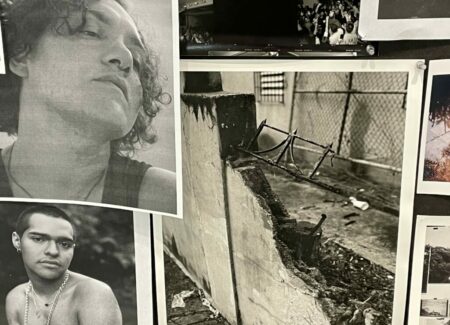

The only two photographs in the show that might be called portraits capture a man named John shadowboxing against a blank wall. Pérez is a boxer themself, and their choice of poses highlights a mix of power and vulnerability. One image finds John covering up with his gloved hands, with sweat beaded on his bare back; in the other, he stretches out with one leg bent, seemingly about to kick, his arm extended and his body open. The two could easily be hung as a diptych, the opposing forces and instincts balancing each other.

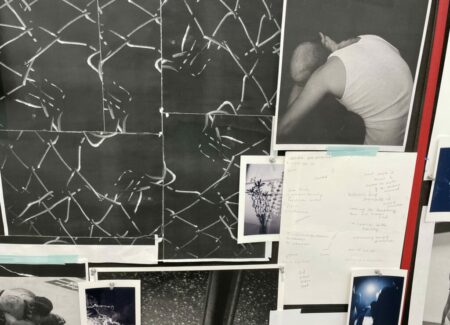

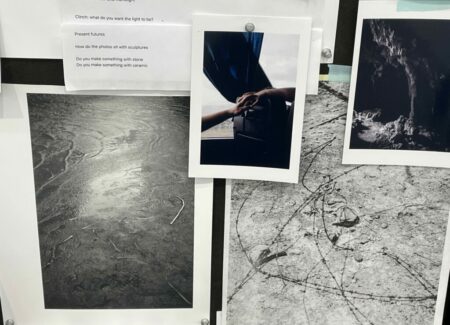

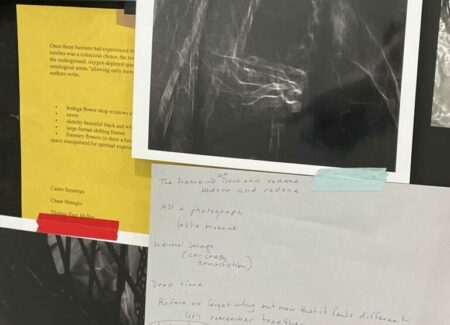

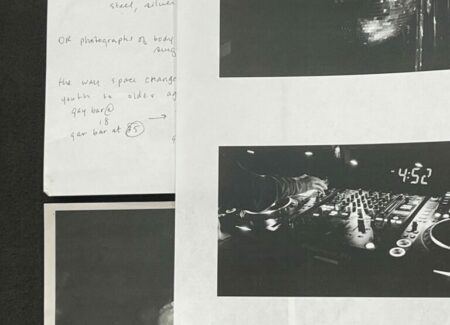

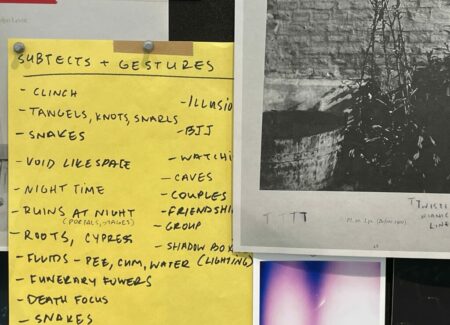

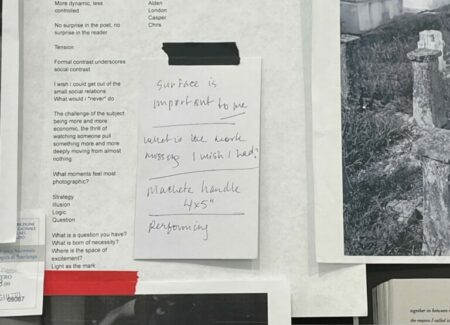

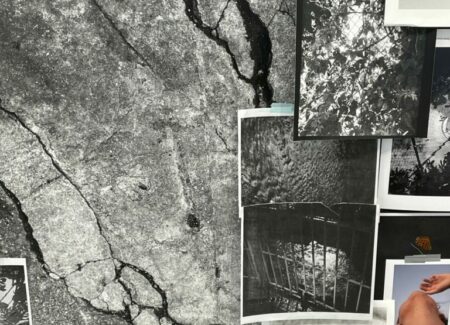

Pérez then leverages the boxing motif one step further, using black padded mats (from the gym) as the substrate for a set of three large scale collaged works, each of which includes a variant image from the boxing shoot in a prominent location. Each work is an assemblage of prints in various sizes (in both black-and-white and color), found imagery, book plates, images of text pages with underlining, and gatherings of lists and note pages (both printed and hand-written). More than mood boards but less than structured arguments, these works follow along as Pérez makes formal and visual connections, tries out combinations, and generally thinks things through, the richness of their ideas coming through strongly. In particular, the texts and note pages allow us to loosely follow their train of thought, the surrounding imagery reinforcing themes and motifs they are exploring. Cracks and dark lines seem to anchor two of the assemblages, while the third mixes florals with bodies and voids, the intermittent text monologue peppered with questions and impulses and the nearby imagery filling out checklists of subjects and gestures. The result is something akin to layered stream of consciousness, where the work of the mind is directed and intentional, while still being artistically open-ended and searching. These assemblages recall Lyle Ashton Harris’s studio wall collages, but with even more intimate windows into Pérez’s churn through conceptual and aesthetic possibilities.

There is a natural tendency with assemblages like Pérez’s to want to try to turn them into rebuses or puzzles that we can then decipher. In this case, that impulse feels simplistic; these works feel more internally process-centric than that, almost like Pérez’s mind wrestling with itself, iteratively problem solving until it reaches some state of equilibrium or satisfaction. When matched with the finished photographs that are hung on the nearby walls, the assemblages feel like evidence of the invisible support scaffolding that lies underneath the pictures; instead of just offering us the photographic “answers”, Pérez has shown us their work, so we can trace back the many thoughtful intermediate steps (and missteps) that led to the finished products.

This is an understated almost muted show, whose richness and complexity seem to grow with time spent. Many of the photographs slowly reveal themselves as elusively luminous and unexpectedly seductive, and the wall of assemblages then draws us into an entire world of meaty artistic thinking. In the process, Pérez reveals themself as a sophisticated photograph thinker, ready to do the artistic spade work required to eventually construct images with consistent depth and resonance. After diving into the assemblages, nothing about Pérez’s approach feels accidental. Clearly, this is a photographer coming into a fuller sense of confidence and craft, becoming more and more willing to bet on following the pathways that make their voice unique.

Collector’s POV: The photographs in this show are priced at $8000, $10000, and $12000, based on size. Pérez’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.