JTF (just the facts): A total of 15 black-and-white and color photographs, framed in silver and matted, and hung against white walls in the main gallery space.

The following works are included in the show:

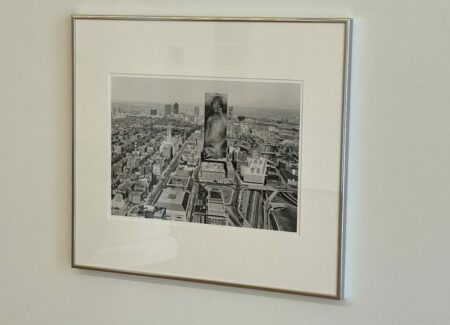

- 13 gelatin silver prints, 2023, sized roughly 9×14, 10×14, 11×14, 12×14, 14×12, 14×14 inches, in editions of 3+2AP

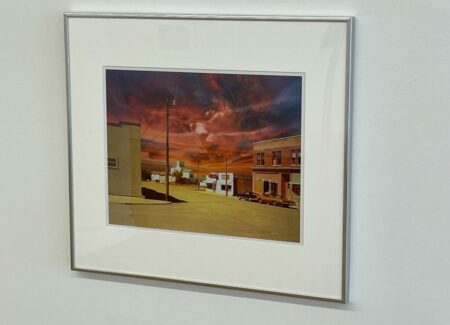

- 2 chromogenic prints, 2023 sized roughly 11×14 inches, in editions of 3+2AP

(Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: For a young contemporary photographer like Erin Calla Watson, just getting her start and still finding and refining her own artistic voice, the photographic trends and historical movements of decades past might very well feel quite removed from the realities of her early career. Coming out of an esteemed MFA program at CalArts, Calla Watson was surely exposed to the milestones and masters of photographic history, but that academic timeline could have easily felt distant (and even less than entirely relevant) when compared to the seductions of the ever-evolving medium in its contemporary digital form.

So it is altogether surprising that Calla Watson would choose the landmark “New Topographics” show from 1975 as the inspiration for her first solo show in New York. Originally curated by William Jenkins at the George Eastman House, “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape” brought together the work of ten then-contemporary photographers whose work was redefining landscape photography. In contrast to the majestic grandeur of nature found in the work of Ansel Adams (and many others), the New Topographics photographers were interested in capturing the changing surfaces of industrialization and suburban sprawl, primarily as seen in America, particularly in the West. Their work was often pared down and austere, documenting housing developments, business parks, warehouses, industrial facilities, and other overlooked structures with matter-of-fact severity. It was an unidealized, conceptual, and sometimes even provocatively bleak vision of the land, with threads of unease sifting through its unvarnished presentation of environmental disregard and sprawling expansion.

Calla Watson was born in 1993, so she was neither alive for the show’s first run, nor particularly old when the show was reprised by Britt Salvesen at the Center for Creative Photography in 2009, so her introduction to the work likely came at school or via the reprinted catalog. But the enduring influence of the New Topographics “movement” on generations of downstream photographers is undeniable, both in its rigorously precise aesthetics and in its prescient documentation of man’s continuing exploitative approach to the land. What’s fascinating is that Calla Watson doesn’t seem to have been drawn to either of these typical entry points to the work, but has instead grafted her own interest in masculinity and male-dominated spaces onto some of the original pictures.

Of the ten photographers originally included in the show – Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, Nicholas Nixon, John Schott, Stephen Shore, and Henry Wessel – only one was female, but the idea that the broader New Topographics vantage point was particularly gendered or male dominant hasn’t been explored in much depth. In a sense, most of the spaces depicted by the photographers were essentially empty or unoccupied, in that there were few if any people overtly captured in the pictures. Calla Watson’s approach has been to repopulate the photographs with a particularly masculine presence, using the male supermodel Jordan Barrett from Australia as her muse. The result is a set of interventions that make the landscapes more “male”, or at least infuse them with a more visible male spirit, which in turn alters our interpretation of the scenes.

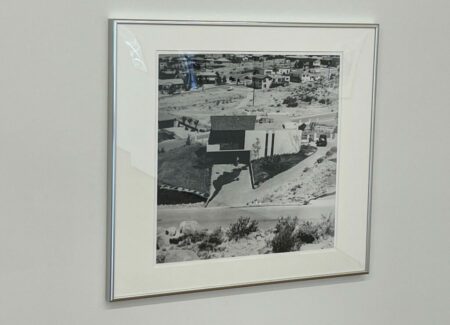

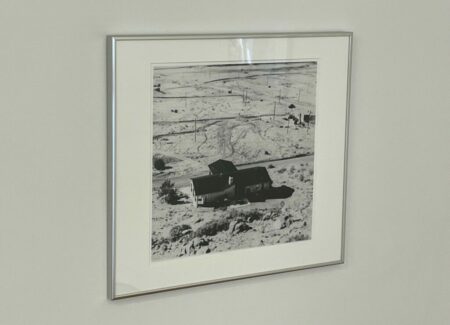

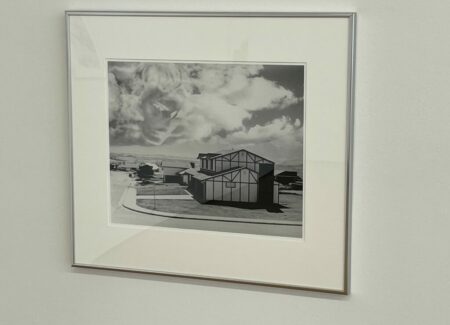

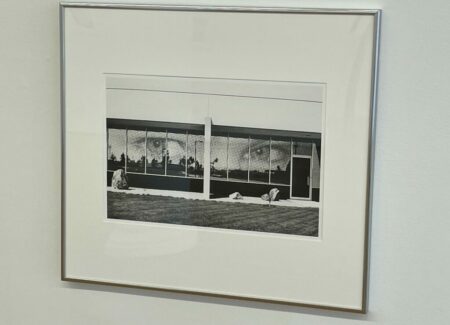

If Calla Watson’s images look a bit grainy and fuzzed, it’s largely due to the accumulated noise from her iterative process. Starting with scans from the catalog, she then digitally manipulates the images (primarily inserting Barrett in one way or another), prints them out, and then rephotographs the prints with 35mm film, bringing the process back around to an analog endpoint. The works have then been matted and framed in shiny silver frames like those used in 1975, mimicking the look and feel of the original show.

Calla Watson’s interventions range from the quietly subtle to the eerily ominous. In a few images, it takes some detective work to find Barrett. He’s been tucked into the shadows under the eaves in Henry Wessel’s house with tall grasses in front, placed in an upstairs window in Stephen Shore’s house with a roof antenna, and stands talking on his phone underneath the porch overhang of John Schott’s diner, and in each case, his presence shifts the narrative somewhat, making him the protagonist in an implied story.

In other images, Calla Watson’s approach is more akin to outdoor advertising, with Barrett’s face and body splashed across building surfaces, in a few cases with such fidelity that it’s hard not to assume that his form wasn’t there all along. Barrett’s big eyes look out from the plate glass windows of one of Lewis Baltz’s flat-roofed industrial buildings, and then his shirtless form gets supersized, covering an entire glass skyscraper in a picture appropriated from Nicholas Nixon. These works are some of Calla Watson’s most successful, mostly because her interventions insert the hypermasculinity with such incisive deftness.

Many more of Calla Watson’s works push her interventions into the realm of fantasy, having playful fun with the different ways Barrett’s visage can be shoehorned into an existing composition. She adds Barrett’s face and silhouette as a water stain on the driveway (in an Albuquerque image by Joe Deal), as a thin shadow in the street (in a Minnesota view by Frank Gohlke), as scrapings in the dirt (in another Albuquerque picture by Deal), and as a pruned bush (in a Route 66 motel scene by Schott). She then goes further, adding Barrett’s face to the clouds, the sun, and the sky above images by Robert Adams and Shore; in some cases, the supermodel is benevolently smiling, and in others, he is staring open mouthed and blank eyed as though angry or possessed, his hovering omnipresence almost God-like.

While the original images included in the “New Topographics” show had their own subtle balances and tensions, Calla Watson’s interventions transform the pictures in powerful ways, introducing seductive male beauty into scenes that were often called ugly when they were first shown. Barrett’s presence adds a charge of energy to nearly every picture, as though the force of his personality was somehow overwhelming the natural rhythms of the various scenes and landscapes. For those raised on the truths of the “New Topographics” photographs, Calla Watson’s pictures muddy the definition of homage, in a sense updating the concerns embedded in the images with new strains of thought. It takes a measure of artistic confidence to embrace an iconic body of work and then boldly reimagine it, and the strongest of the images here deliver on that promise, mixing reverent familiarity with a fresh conceptual twist.