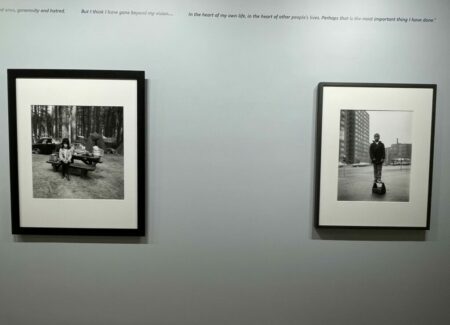

JTF (just the facts): A total of 26 black-and-white photographs, framed in black and matted, and hung against light grey walls in the single room gallery space and the entry area.

The show includes the following works:

- 20 gelatin silver prints, 1957/later, 1959/later, 1960/later, 1962/later, 1963/later, 1965/later, 1966/later, 1973/later, 1977/later, sized 24×20, 20×16 inches (or the reverse), in open editions

- 6 gelatin silver prints, 1959/c1959, 1959/no later than 1966, 1959/1970s, sized roughly 8×10, 14×9, 10×7, 6×10, 5×8 inches

A monograph of this body of work is forthcoming from Steidl (here).

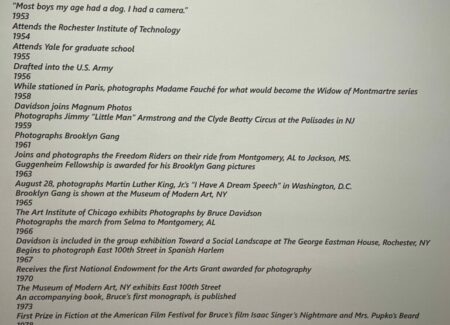

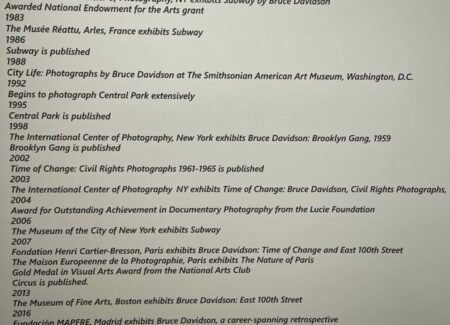

Comments/Context: As Bruce Davidson approaches his 90th birthday, it seems altogether appropriate that he would be thinking about the summation of his long photographic career, and perhaps musing to himself about the “ones that got away” for one reason or another. This small but handsome show, and a larger accompanying photobook, finds the master photographer taking another personal foray into his archive, unearthing previously unpublished images from various projects, assignments, and geographies, including selections from some of his most famous series from the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.

The word “another” is important here because back in 2010, Davidson released a mammoth three-volume boxed set of images drawn from a similarly broad sweep of his own photographic time. Weighing in at more than 800 images, we might have assumed that “Outside Inside” (as the set was titled) would represent Davidson’s definitive final word on which pictures he thought deserved attention. But here we are, more than a decade later, with Davidson still digging through the storage boxes and contact sheets, and offering up even more variants, outtakes, overlooked images, and other rarities.

Back at the time of Davidson’s first edit for now well-known projects like “Circus” (1958), “Brooklyn Gang” (1959), “Time of Change” (1961–65), and “East 100th Street” (1966–68), he was naturally forced to make hard choices and to leave certain images out, likely making determinations that they were too similar to pictures he had already included or not strong or additive enough to make room for. Such decisions may have been constrained by page counts, particular themes or narratives he wanted to create, or even by his view of their resonance with the broader cultural moment around him.

What’s intriguing about Davidson’s nested rediscovery process of the past two decades is that it has allowed for reappraisals and revisions of those initial judgments. Simply put, pictures that weren’t “good enough” to get in the books back then (for whatever reason) can now be seen again with fresh eyes, and with both the benefit of hindsight and an acknowledgment of the changing cultural atmosphere. Particularly for pictures that might have been the 55th or 60th “best” in a group previously limited to 50, we can now see these omitted images outside that strict context as individual stand alone photographs, and judge them solely on their merits.

The good news is that nearly all of the photographs included in this show feel warmly familiar, to the point that those less deeply versed in exactly which pictures were included in which books could easily conclude that these outtakes were indeed primary selections. This of course tells us important things about the long term consistency of Davidson’s eye and the depth of the archive from which his projects were drawn – many of the images that ended up on the cutting room floor were solid, and are still very much worth considering.

Davidson’s “Brooklyn Gang” project is the best represented in terms of the number of inclusions in this show, and the understated subtlety found in the photographs is what ties them together. Several of the images capture the teenagers lounging and smoking underneath the boardwalk or quietly enjoying the beach. One picture featuring a tangle of resting arms is emblematic of the kind of emotional intimacy Davidson was often documenting, the struggle of their young lives released for just a moment while snoozing on the sand. Other photographs notice particular details or small gestures that seem to cut against the rough stereotype of “gangs” – the broad back of a white t-shirt at a dance, the careful combing of hair using a storefront window as a mirror, and even the catching raindrops in cupped hands on a wet sidewalk.

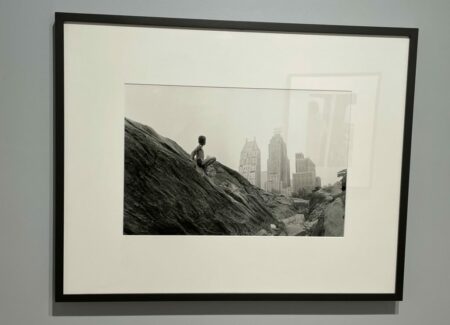

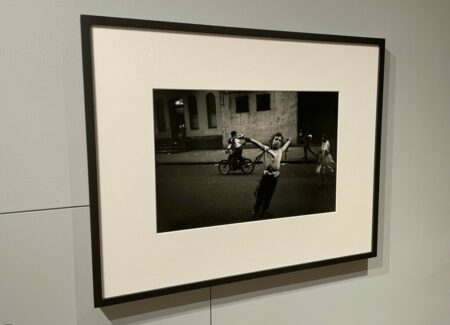

Davidson’s empathetic humanism comes through in a range of other images, many seemingly single frames made outside the more directed gaze he employed during his longer projects. The people of New York City are a common subject, with children playfully standing under the water streaming off a Lower East Side awning, looking upward at the looming skyline from the massive rocks in Central Park, and exultantly parading arms wide through the streets; these scenes are then bookended by images of grumpier looking adults caught in a cafeteria (with a full glass of milk) and on a subway platform. In each case, Davidson finds a thread of fleeting emotion or humor in the moment, where a picture becomes the beginnings of a story.

In many ways, The Way Back is an exercise in nostalgia, with faint refrains from visual tunes we already know and love meandering through the air. But the show also points to the durability of Davidson’s world view, and its consistent return to observing people with attentive compassion. The fact that his overlooked outtakes are still engaging and compelling is proof positive that he’s been doing something right all along.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced as follows. The vintage (and roughly vintage) prints are $18000 each, while the modern prints are $5500 or $9000, based on size. Davidson’s work has become more consistently available in the secondary markets in the past few years. Recent prices have ranged between roughly $1000 and $30000.