JTF (just the facts): A total of 83 photographic/video works by 17 artists/photographers, variously framed and matted, and hung against white/yellow walls in a series of connected spaces on the third floor of the museum.

The following artists/photographers have been included in the show, with the number of works, their processes, and their dates as background:

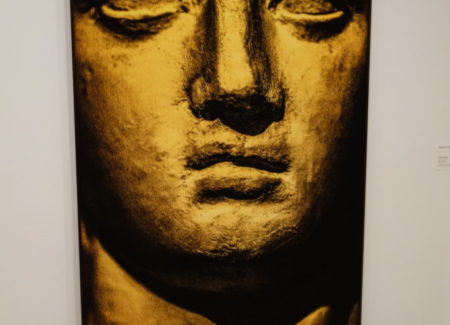

- Sofia Borges: 3 pigmented inkjet prints, 2014, 2017, 1 UV printed wallpaper, 2014/2018

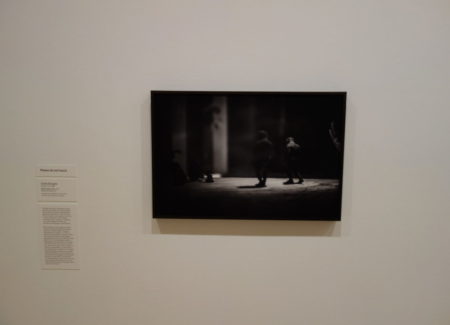

- Matthew Connors: 15 pigmented inkjet prints, 2013, 2016

- Sam Contis: 3 pigmented inkjet prints, 2014, 2015, 3 gelatin silver prints, 2015, 1 two channel video, 5 minues 5 seconds, 2018

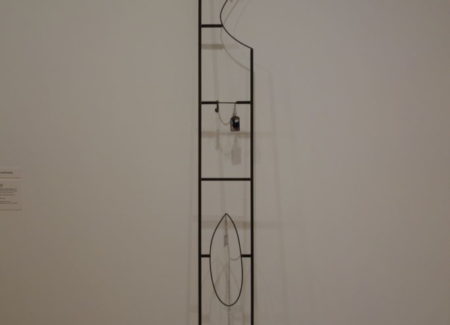

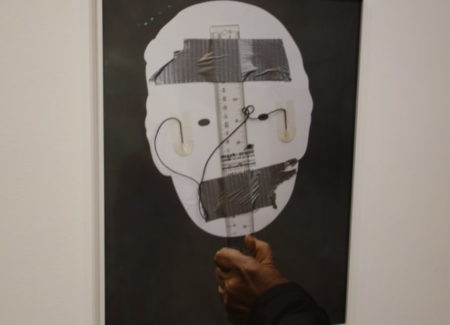

- Shilpa Gupta: 4 works made from pigmented inkjet prints in split frames, 2014

- Adelita Husni-Bey: 4 chromogenic color prints, 2018

- Yazan Khalili: 1 video, 7 minutes 30 seconds, 2016

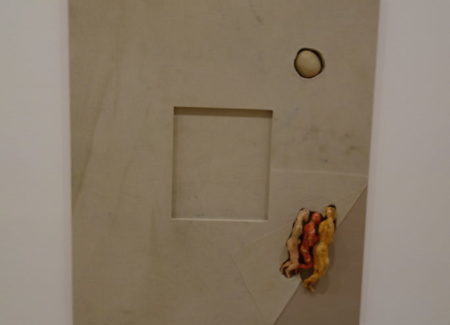

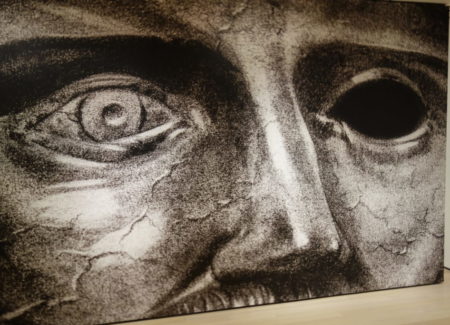

- Harold Mendez: 1 pigmented inkjet print with graphite, 2017-2018, 1 pigmented inkjet print, 2017-2018, 1 cotton, graphite, spray enamel, toner, litho crayon on ball grained aluminum lithographic plate on dibond, 2017-2018

- Aïda Muluneh: 5 pigmented inkjet prints, 2016

- Huong Ngo and Hong-An Truong: 1 work made from pigmented inkjet prints (9) and laser cut prints (6), 2016

- B. Ingrid Olson: 3 UV printed MDF, PVA size, Plexiglas, screws, 2017, 2 inkjet print and UV printed mat board in aluminum frame, 2016, 2017

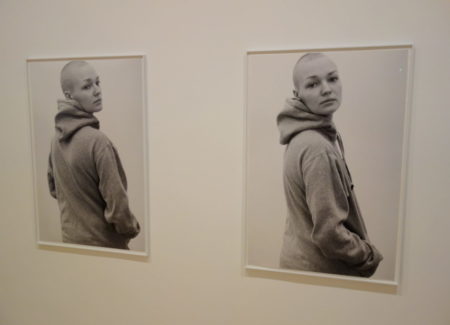

- Joanna Piotrowska: 5 gelatin silver prints, 2013-2014, 2016

- Em Rooney: 6 multi-media works, various made from hand colored gelatin silver prints, chromogenic color prints, steel, leather, picture key chains, and other materials, 2015, 2016, 2017

- Paul Mpagi Sepuya: 6 pigmented inkjet prints, 2015, 2016, 2017

- Andrzej Steinbach: 9 pigmented inkjet prints, 2015, 2017

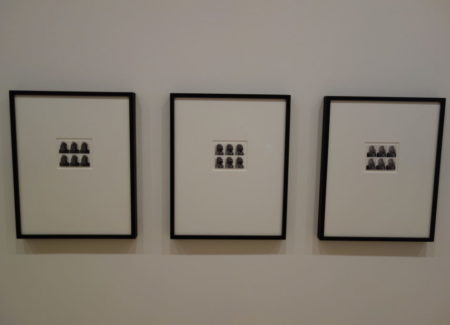

- Stephanie Syjuco: 7 pigmented inkjet prints, 2013-2016, 2013-2017

- Carmen Winant: 1 installation made from found images, tape, 2018

The exhibit was curated by Lucy Gallun, Assistant Curator, Department of Photography.

(Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: The thematic group show is a staple of the art world summer. In many ways, these shows are a predictable response to a collection of stubborn realities – it’s often hot in a place like New York (sometimes stiflingly so), the crowds of real collectors have noticeably thinned and been replaced by casual tourists making the rounds, the overall intensity of activity is way down, and few artists are particularly eager to show their new work during the off cycle. So galleries respond by putting together catchy thematic shows, often drawn from the gallery’s own stable and augmented by a few key loans from other places, bringing together a broad group of work that covers a lot of bases. And while there is sometimes an element of fun in all of this, the downside to such an approach is that these shows tend to be wildly uneven in terms of quality (almost by definition) and as a result are largely forgettable (and forgotten). But the weather is warm and everyone is thinking about vacation, so no one protests too much.

While the Being: New Photography 2018 version of MoMA’s now every-few-years survey of what’s going on in contemporary photography actually opened in March, it mostly feels like a gallery summer group show expanded for the wider scale of an institutional setting. No longer a tightly edited review of two or three notable new photographers, the survey was significantly expanded in the revamped 2015 version of the once annual event, and that broader, more inclusive template has been applied once again here. Being draws 17 photographers/artists under its expansive thematic umbrella, each one (or pair) represented by a handful of works displayed on a wall or two. So instead of the grab bag of single works found in many summer gallery shows, here that framework has been supersized, giving each photographer a bit more breathing room to communicate his or her story with a slightly larger sample of work.

When MoMA rolled out the new structure of this series with Ocean of Images: New Photography 2015 (reviewed here), the first theme focused on how photographic images were circulating in our networked world, how they were being used and reused, and how the medium itself was being transformed by this process. This approach was necessarily inward looking, with a heavy dose of conceptual photography-about-photography undercarriage, and was generally right on target for what was happening at that moment in contemporary photographic time. But the exhibit’s cerebral coolness and conceptual dryness left some visitors appropriately wondering if photography was losing its ability to actually relate to the real world in an engaged manner. It was largely an ideas show rather than a people show, and that separation felt significant.

So it is not altogether surprising that the theme for this year’s version of the exhibit has emphatically swung back toward humanity – not only did the curatorial balance need righting, the wider world has become enflamed by definitions of who we are (and aren’t), what categories we fall into (or don’t), and how we measure and consider ourselves. Whether by gender, or sexuality, or nationality, or political leaning, or citizenship status, or any number of other signifiers or labels, we are of late constantly being forced to choose sides, to impose boundaries, and to self-identify, and the photographers who are included in this show are broadly wrestling with these issues.

“Broadly” is the key modifier here, because Being is about as sprawling a theme as one could reasonably use to organize a group of pictures, and this is where the power of the concept starts to unravel a bit. Questions of why these particular photographers and not others, or why these hot button subjects and not those, or why these photographic strategies and not alternates, become harder to answer given such an amorphous construct as the organizing principle. Nearly any contemporary photographer who takes pictures of humans, either directly or indirectly/abstractly, could have reasonably been included within these confines, and that flexibility undermines the ultimate incisiveness of what has been chosen here, leading the whole exercise back into the mundane realm of the summer group show.

The good news is that aside from one wonderfully bold and provocative exception, most of the photographers included here have taken indirect approaches to thinking about the humanity of their subjects, and this deliberate misdirection leads to some unexpected insights and perspectives.

Two photographers we have reviewed previously employ photographic illusionism as a pathway into a deeper exploration of self. Paul Mpagi Sepuya uses mirrors, drapery, and multiple layers of studio-based rephotography to interrogate his own sense of being black and gay, and the recent images included in the show create interrupted barriers to seeing, collapse space, and slice imagery into thin strips of fragmented possibility, all part of a complex sense of identity construction. And B. Ingrid Olson offers two unique approaches to seeing herself, one using imagery printed on the surrounding mat boards, creating a telescoping set of references and layers, and a second adding the depth of a clear Plexiglas box to further confound our understanding of (and interaction with) the mirrored photographic inversions. Also included in this group of illusionists is the German photographer Andrzej Steinbach. At first glance, his selection of large scale portraits looks like a chopped up fashion frieze, with adjacent individuals separated out into single frames. But a closer look reveals that the work is made up of only three women, who change positions (standing, sitting, and crouched/kneeling) and rotate outfits, creating a interwoven nest of possible personalities and relationships. For all three artists, the discrete individual becomes multiplied out, quickly extending from one to many.

Another cluster of photographers come at the idea of identity by unpacking the signifiers, descriptors, and surfaces that define who people are, often incorrectly. Stephanie Syjuco dresses herself in densely patterned garments and fabrics purchased at big box stores, mimicking the “exotic” “ethnic” dress of people from different cultural backgrounds; she also covers the faces of individual sitters in passport-style headshots, reducing our ability to see them as anything but misinterpreted stereotypes. Shilpa Gupta’s works represent people who have intentionally changed their surnames. Using divided images that are shuffled and reassembled in mismatched order, the constructions feel like lives turned into slippery misaligned fragments, where meaning and identity are constantly in flux. And Matthew Connors travels to North Korea, where the controlled surfaces of a carefully managed culture provide both a propaganda-style reality and fleeting glimpses of something more real. In all of these bodies of work, the exterior largely fails to represent the personal nuance and complexity of what lies underneath.

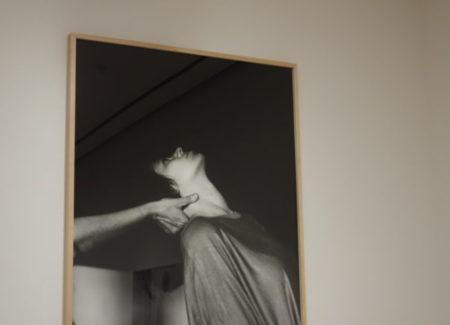

Two of the most durably powerful studies of human interaction on view here come in the form of old school photographic attention to gestures, where the placement of a hand, the turn of a head, or the gentleness of an embrace speak volumes about the subtle relationships of people. For Joanna Piotrowska, a tangle of bodies, a hand supporting a neck, a touch on the shoulder, and a fort made of a table and chairs all signify an intimate sense of closeness and belonging. And for Sam Contis, a tight embrace, the pull of a bloody cloth, the gender ambiguity of a cowboy hat or a denim dress, and the oil stained fingers of a working hand sensitively interrogate the layered meanings of masculinity and companionship.

But the showstopper in this uneven survey is undeniably Carmen Winant’s engrossing installation My Birth. Hung floor to ceiling on two relatively narrowly spaced walls (thereby pulling visitors into close proximity with the imagery), Winant’s found images of childbirth don’t need any of the indirectness, reconsideration, or thoughtful abstraction that the other works in this show employ to convey their messages. Instead, they confront us bluntly and openly with something profoundly human, showing the many stages of childbirth, from early term pregnancy to the physical pain and emotional intensity of pushing and delivery, pulling back the curtain on the joy, anguish, tenderness, fear, and love that make up the wrenching and life changing process of giving birth to a child. Given that these kinds of images haven’t been and still aren’t shared in popular culture very often, their power here seems doubly enhanced – and Winant’s forceful and honest installation thunderously reclaims this most natural of female realities from those who would push it into the shadows. (The photobook version of this work has been reviewed here).

It used to be the case that the New Photography exhibits at MoMA brought with them a sense of institutional approval and well informed advocacy, a feeling that the artists who were selected for these shows were being anointed as figures who were likely to be important to the development of the medium on a going forward basis. This is really no longer true. Perhaps because the medium has expanded to such an extent that understanding all of its facets has become an almost impossible task, the broader thematic shows that now bear the New Photography title don’t pretend to make such profound pronouncements, and the wide range of work on view in Being can’t help but have a questionable mix of quality.

But beyond the often insightful conclusions of its included works, what Being really signals is a more sustained commitment on the part of the museum to being inclusive rather than authoritative, at least as far as these samplers of what’s new in photography are concerned. I for one will miss the riskiness that taking a stand on durable importance forced on the curators, and stepping back from those kinds of tough choices inevitably dilutes the results. In the end, bringing together a collection of related pictures that will mildly appeal to all is of course a safer path forward, but it unfortunately misses the chance to radically change or redirect the wider conversation.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum show, there are of course no posted prices. While many of the included artists have established gallery relationships, few have a secondary market history that can be tracked in any quantifiable way. So given the large number of artists included in the group show, we will forego our usual in depth discussion of these relationships and market results.