JTF (just the facts): Published by Edition Patrick Frey in September 2019 (here). Hardcover, 104 pages, with 48 black and white illustrations. In an edition of 800 copies. Includes writings by the artist. Designed by Brian Paul Lamotte. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Marcia Resnick made her artistic name documenting New York City’s “bad boys” in the late 1970s and 1980s – a group of high profile male artists, writers, and musicians, including William Burroughs, John Belushi, Mick Jagger, David Byrne, and Andy Warhol, and others. The daughter of two artists, Resnick grew up in South Brooklyn, and her parents always supported her artistic inspirations. She had her first show at the age of five; her drawing of a blonde Asian woman standing on a stage was shown at the Brooklyn Children’s Museum. Resnick later moved to Manhattan to attend New York University and later Cooper Union, and almost right away got drawn into the counterculture of the 1960s. She did her masters at CalArts (studying with John Baldessari) and returned to NYC in the mid 70s.

As Resnick got immersed herself in NY art scene, she became an insider who captured the cutting-edge world of punk. Inspired by the feminist movement, she embraced the idea of a confident independent woman, and given that there were very few women photographing famous men at that point, her work was pioneering. Resnick says “the Women’s Liberation movement motivated me to turn the tables and photograph men,” subjecting them to the female gaze. Her lesser known series Wild Women documented the creative energy of women artists, including Susan Sontag, Lydia Lunch, and Joan Jett.

In 1975, Resnick had a car accident, crashing into a pole in the West Village, and was hospitalized for two weeks. The accident forced her to look back at herself and her life memories. Soon, she started to use photography to explore identity, and as a result, in 1978 she released a photobook consisting of a series of staged photos of a female model exploring adolescence. It was published by the Toronto-based Coach House Press and titled Re-Visions. This year, forty-one years later, the Swiss publisher Editions Patrick Frey has re-published the book, thereby introducing Resnick’s landmark series to a wider audience.

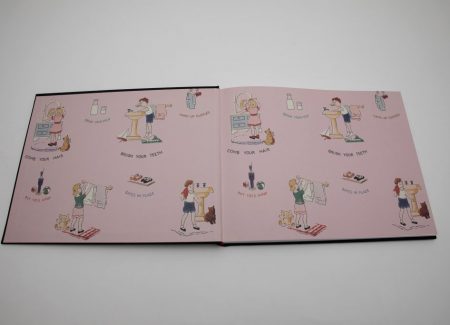

Re-Visions is dedicated to Humbert Humbert, the narrator of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. The photograph on the book cover is inspired by the film poster of Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita; it is a close up portrait of a young girl looking straight at us as she seductively lowers her heart shaped glasses. Resnick says that for her this image “represents the idea that behind the veneer of normalcy (the glasses), the traumas and sexual confusion of adolescence resides.” The book is covered in a lush black fabric, and the artist’s name and the title are elegantly placed on the spine in red. The end papers feature innocent illustrations depicting a girl and a boy doing their daily routines – “comb your hair”, “drink your milk”, “hang up clothes”, “put toys away”, it reads like a happy sing-song list of parental tips. But the visual flow that follows shows that coming of age is all about breaking these kinds of rules.

In the series, Resnick creates intimate portraits of a fictional teenage girl and combines them with short writings, recording the experience of growing up as a woman. The unnamed protagonist is referred to in the third person “she”, becoming a more universal reference to an everywoman female character. Just like the original edition, the book opens with appraisals and blurbs by a number of Resnick’s contemporaries. “Not bad, really” reads a quote by William Wegman, and “… the essence of adolescence”, notes another from William S. Burroughs.

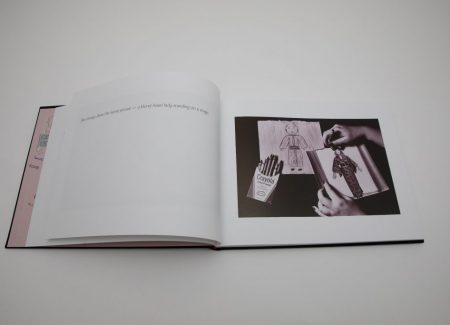

The first photograph depicts an initial moment of reflection: a girl in saddle shoes embraces her legs as she sits with notebooks and a pencil, with chocolate cookies, cupcakes, marshmallows, and a glass of milk sitting nearby. The text on the left reads “She learned about morality at an early age. Innocence gave way to Good and Evil … everything appears to be black and white.” The cleverness of this image and its word-play, and the contrasting tonalities and physical layering of schoolwork and treats in the photograph, lets us know that Resnick is approaching her chosen subject with witty sophistication. This image is followed by another built on a reference to her original drawing a blond Asian lady, bringing a personal element of her own story into the project.

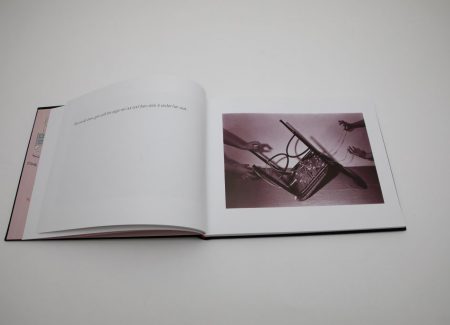

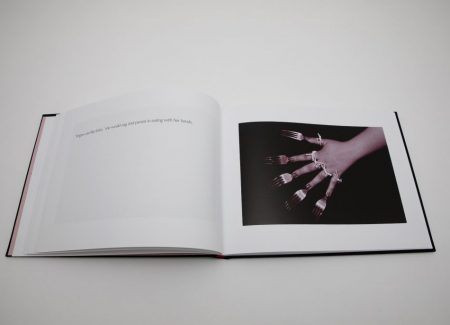

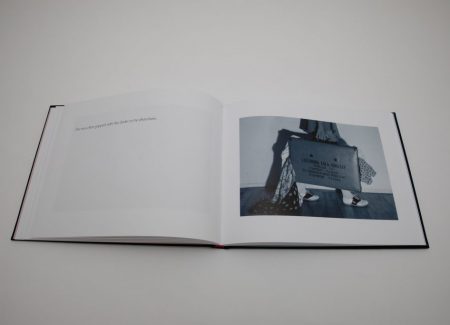

The photographs and writings, in bold and often bitingly funny ways, track various moments and struggles of growing up female. A photo of an upside down desk chair with a dozen blobs of chewing gums suck underneath and two pairs of hands pulling them into sticky strands is paired with “she would chew gum until the sugar ran our and then stick it under her seat.” Resnick’s heroine appears as she misbehaves at school, avoids a spin-the-bottle game, scotch-tapes her nose before a date, stuffs her bra, and dresses up in striking outfits. A number of the images reference the feeling of not fitting in, or being isolated, in ways that feel authentic.

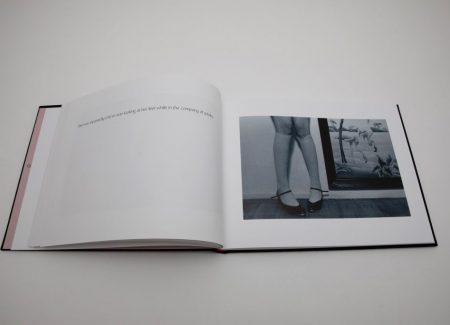

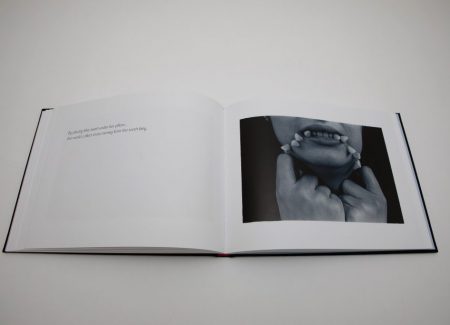

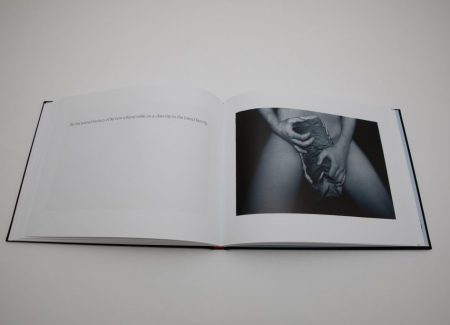

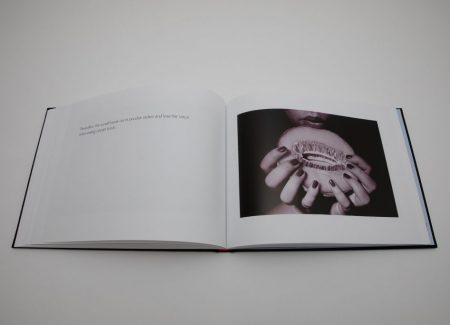

Other images explore adolescent sexuality – they feel slightly naughty and stress a self-awareness of no longer being entirely innocent. “She secretly lusted for her television idols” is paired with a strange photo of a girl tongue-kissing a Howdy Doody doll. Another picture shows a cropped nude body tensely gripping a loaf of sliced bread between her legs, with the caption “she first learned the facts of life from a friend while on a class trip to the bread factory.” Resnick amplifies her girlhood memories to dramatic and humorous effect, her ingenious makeshift staging adding to the sharpness of the scenes.

Resnick says that working on the Re-Visions prepared her to be “sensitive to independent, self-aware, creative women functioning in a “man’s world.” Re-Visions is an important photobook by a woman photographer that deserves to be more consistently included with other feminist photography classics from the 1970s. These images are filled with a healthy and knowing sense of irony, and should be more often mentioned in the same breath with Cindy Sherman’s early work, as well as projects by Birgit Jürgenssen, Martha Rosler, and others who explored the conflicts between women’s roles and their interior lives at that time. This current reprint edition, with its meticulous attention to color reproduction and printing quality, seems as relevant and engaging today as it originally was in 1978.

Collector’s POV: Marcia Resnick is represented by Deborah Bell in NYC (here). Her work has not found its way to the secondary markets with much regularity, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.