JTF (just the facts): A total of 25 black and white photographs, framed in black and matted, and hung edge to edge against white walls in the smaller project room gallery space. All of the works are gelatin silver prints, made between 1970 and 1972. Each is sized roughly 8×8 inches and no edition information was provided. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: In 1970, Ralph Eugene Meatyard discovered he had terminal cancer, and began to work on what would be his last artistic project. The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater was designed to be a photobook, a carefully sequenced “photographic poem” consisting of seventy portraits of his wife Madelyn and his children, friends, and neighbors wearing a pair of rubber Halloween masks purchased at the drugstore. After Meatyard died in 1972, the book was posthumously published in 1974 and subsequently became his most widely recognized body of work.

A licensed optician and self-taught photographer who first picked up a camera in the mid 1950s, Meatyard began making an artistic name for himself quite quickly. He studied with Minor White and Henry Holmes Smith in 1956, had his first two-man show with Van Deren Coke at A Photographer’s Gallery in New York in 1957, and was selected by Beaumont Newhall for the “New Talent in Photography USA” section of Art in America in 1961.

What made Meatyard’s pictures stand out (especially against the backdrop of the photoconceptualism of the late 1960s) was their unexpected strangeness, particularly their placement of mystical darkness and eccentricity within a seemingly typical Midwestern family life setting. Children cavorted amid rotting barns, in empty rooms, and amid nearby forests, their play often turned gothic by dark shadows, blurs, and mirrors. The deliberate moodiness of the photographs hinted at the secrets, undercurrents, and shifting psychological states in the residents of his patch of Kentucky farmland, and was reinforced by a unique brand of lyrical formalism that situated his subjects amid the lines and contrasts of the rural architecture.

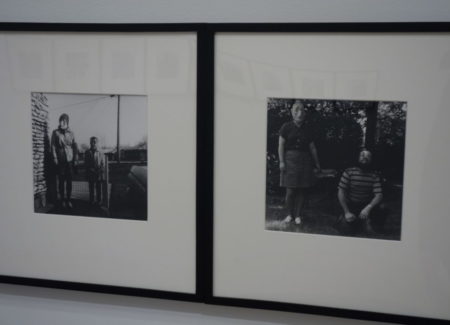

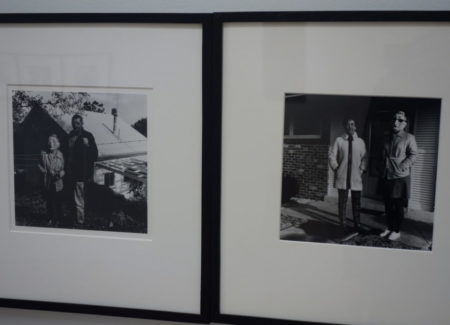

While Halloween masks had made a few intermittent appearances in his works prior to the Lucybelle Crater series – adding a sense of uneasiness and ominous friction to otherwise serene portraits – Meatyard leveraged what he learned in these initial experiments and went on to embrace the unsettled weirdness of the mask motif more fully in his final project. The images in the series all have the same general format – two figures pose in what, at first glance, appear to be standard American outdoor portraits, the kind you might find in mid-century family albums from all across the country. The first figure is consistently Meatyard’s wife, wearing a witch mask with a warty nose, bulging eyes, and hair in a bun. The other figure is drawn from a rotating cast of family, friends, and neighbors, each of whom (regardless of age or gender) wears a transparent mask of an older man’s face. The two figures typically stand side by side, or perhaps sit together somewhere outside.

Aside from the masks, the trappings and details of these portraits are resoundingly modest and white middle class. Madelyn often wears a khaki trench coat, with a dark skirt and white shoes, or a humble blazer; men are either in suits or in 1970s casual; and kids are in flared pants, or combinations of shorts and tank tops. The settings are equally predicable and mundane – in backyards, on patios, near front doors, next to parking areas and garbage cans, or close to ivy walls or prickly wintertime bushes, with playground equipment and drying peanuts providing the only deviations from the parade of typical real estate features.

But the masks of course make all this conventionality seem altogether odd and almost comic. Familiar faces are now sort-of unknowns, and that inconclusiveness is unsettling. The inversions of ladies as men, kids as men, and bearded men as clean shaven ones (although their beards still show through just a bit) created by the second mask add to the puzzling sense of being deliberately wrong-footed. Meatyard then enhances this uneasiness with his conscious control of shadows, allowing trees to cast spooky craggy forms on nearby walls or encouraging shadows to directly interrupt the portraits, with dark dappled leaves blocking faces. And in a few cases, the artist even throws his own looming shadow into the mix, inserting a third figure into the composition. All of this creates pictures that have the structure of something forgettably straightforward but the essence of something quietly freakish and dramatic.

It is this balance between the quaint and the peculiar, or the everyday and the grotesque, that gives these photographs their durable vitality – they’re as compelling today as they were forty years ago. If this show had been a full restaging of the entire Lucybelle Crater series, I think it would have been even an more powerful introduction for those who aren’t already familiar with the work. But even as a sampler of pictures, Meatyard’s masked figures retain their incongruous deviant energy, turning a family album into something altogether original.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced at $9500, $11000, or $11500. Meatyard’s work is consistently available in the secondary markets, with a handful of lots coming up for sale every year. Prices for his vintage works have generally ranged between $2000 and $35000, with most under $10000; a few posthumous prints/portfolios were also made, and these prints have typically been sold for under $2000.

I rate the optician from Normal, Illinois, as one of photography’s greatest. How many people can make snapshots of their family and out-weird Arbus or confound more than Jeff Wall? He was a visionary, who somehow made it all look so incredibly easy.