JTF (just the facts): A total of 43 black-and-white photographs, variously framed and matted, and hung against white walls in the main gallery space, the entry/reception area, and the office areas.

The following works are included in the show:

- 1 gelatin silver print on carte postale, 1919, sized roughly 3×4 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1920/1950s, sized roughly 8×9 inches

- 1 gelatin silver contact print, c1920, sized roughly 2×2 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1919, sized roughly 2×2 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1921/1960s, sized roughly 11×14 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1919, sized roughly 2×2 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print on carte postale, mounted to vellum, 1925, sized roughly 3×3 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print on carte postale, 1925, sized roughly 3×4 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print mounted to vellum, 1926, sized roughly 3×4 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print on carte postale, 1927, sized roughly 5×3 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1926, sized roughly 3×6 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1933, sized roughly 7×9 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1926, sized roughly 9×7 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1928, sized roughly 9×5 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1929, sized roughly 9×7 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1930, sized roughly 9×7 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1931-1933, sized roughly 9×7 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1914, sized roughly 3×4 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print on carte postale, 1927, sized roughly 4×3 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1926/c1960s, sized 10×8 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1933, sized roughly 9×7 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1933, sized roughly 9×6 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1930, sized roughly 9×7 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1933, sized roughly 7×9 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1926/c1944, sized roughly 10×8 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1930, sized roughly 7×10 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1936, sized roughly 14×10 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1928/c1967, sized 8×10 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, c1927, sized roughly 8×6 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1936, sized roughly 5×5 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1928/c1960s, sized 14×11 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1926/c1967, sized 14×11 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print on original mount, 1929/1960s, sized roughly 11×14 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print on original mount with signed overmat, 1929/c1960s, sized roughly 10×14 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print on original mount, 1928/c1960s, sized roughly 9×8 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1933/c1940s, sized roughly 9×7 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1928/c1970, sized 10×8 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1927/c1940s, sized roughly 10×8 inches

- 1 ferrotyped gelatin silver print mounted to board, 1929/c1950s, sized roughly 9×8 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print on carte postale, 1926, sized roughly 5×3 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1931, sized roughly 9×7 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print 1927, sized roughly 9×7 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1927/c1940s, sized 10×8 inches

(Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: In contrast to the summer group shows that take little or no thinking to visually consume, this compact survey of some of the aesthetic trends found in the early works of André Kertész asks us to look more closely at how the young photographer was developing his eye. Covering roughly the first two decades of the artist’s career (from the mid 1910s through the mid 1930s) and following his move from Budapest to Paris, it’s a smart vintage show filled with visual experiments and subtleties, with an argument to be made about his evolving sense of Modernism.

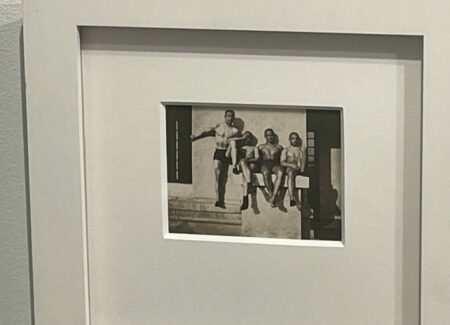

The show begins with a 1914 image made in Hungary, when Kertész was just 20 years old. In it, a group of shirtless young men sit on the stone steps of an unnamed building, and while these men might go onto to become soldiers in World War I, for the moment, they are lounging, looking into the brightness of the sun. But Kertész does more with this casually posed scene than we might expect, using the geometric patterns of the steps, windows, and shadows to build up a more complex composition, leveraging the contrasts of light and dark to energize the scene. Other pictures made in these early years in Budapest offer a similar sense of trying out visual possibilities, like a 1920 from-the-back view of a couple peering through a fence at the circus, where the lines of the wall, sidewalk, and wooden slats further arrange the surrounding space.

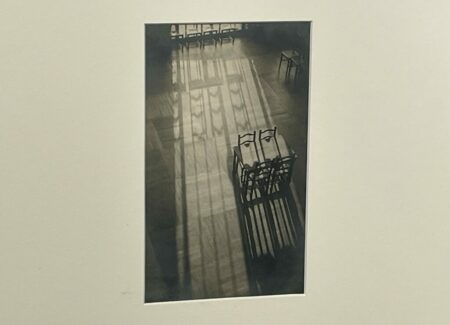

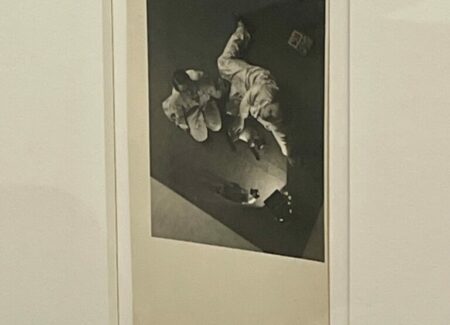

Kertész moved to Paris in 1925, and throughout the next decade, he continued to actively challenge and refine his photographic vision, extending some of the visual ideas he had begun to explore back in Hungary. Steeper camera angles, which later became a signature approach for many Modernist photographers, were a particular area of testing and investigation. The show gathers together a handful of images where Kertész looks down from above, reorienting the scenes and flattening the spatial distances. He peers down at visitors on the platform at the Eiffel Tower, at beachgoers at Dieppe, at a nude woman sunbathing in a rooftop solarium, at the chairs and elongated shadows at a reading room in the American Library, and at his friends Edwin and Peggy Rosskam, each view turning the expected into something more avant garde. He also tries a sharp side angle along the Boulevard des Invalides, pulling us down the sidewalk as the large letters on the nearby wall stretch out.

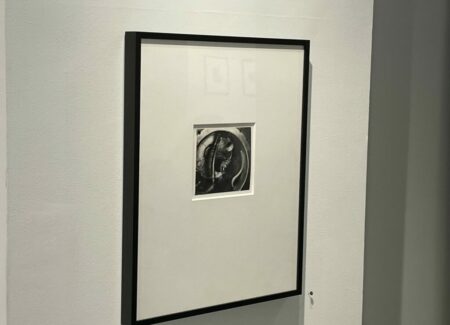

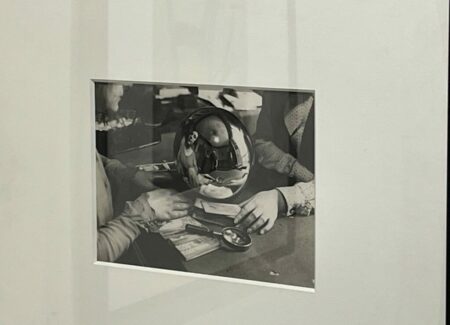

The playfulness of Surrealism and Dada were undeniably in the artistic air in Paris at this time, and many of Kertész’ pictures find him actively looking for the visual strangeness hiding in plain sight. He sees the creepiness of stacked carousel horses and the back of a billboard featuring a waiter carrying a tray. He tries out various kinds of distortions, using a fun house mirror to reconfigure nudes and portraits and a mirror ball to twist a tabletop scene with a fortune teller. And he leans into perplexing poses, including his famously angled “Satiric Dancer” splayed on a couch and an even more puzzling hand grasping (or perhaps fixing) an unidentifiable metal machine.

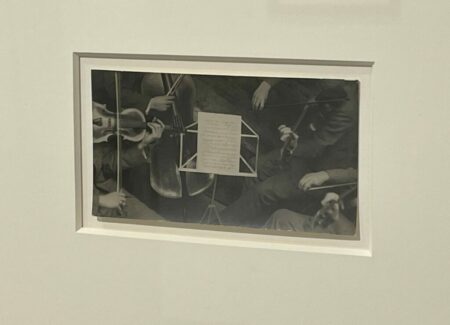

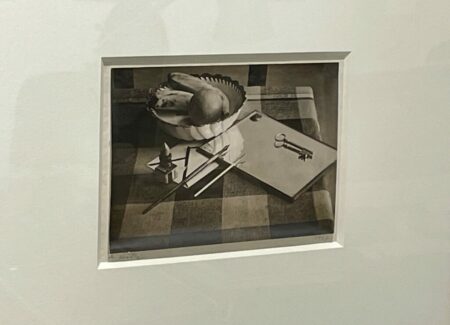

There are several strong still lifes in this selection of works, showing how Kertész was paring down at least some of his compositions to the elemental forms for which between-the-wars Modernism has come to be known. His 1928 study of a fork leaning on a white dinner plate is a well known classic, but his tightly cropped view of a musical quartet (from 1926), with their instruments and music stand pushed into close proximity, is equally inspired. A still life study of a key sitting on a mirror, with various writing instruments and a bowl of fruit placed atop a plaid table cloth, is filled with carefully controlled angles, squares, and curves, as is his view of a horn hanging off the side of a simple chair, the shiny brass providing a contrast to the muted textures of the woven rush seat. Each of these photographs is a precise study of form, the available objects arranged with exacting clarity and care.

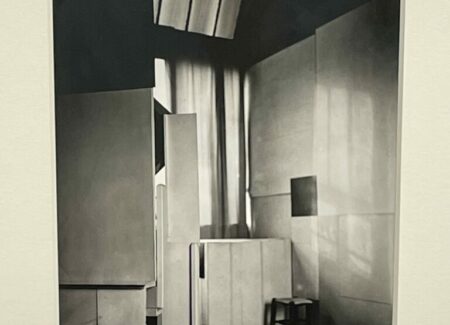

Kertész was part of a vibrant community of artists in Paris, and his portraits of Chagall, Brancusi, Calder, and Mondrian attest to the closeness of these relationships. More intriguing are Kertész’s portraits of artist’s studios, as the aesthetics of their work spaces often tell us more than their faces. Mondrian’s studio (as seen in a 1926 photograph) is all flat planes and strict geometries, the panels, curtains, and windows chopped into layers of blocks and rectangles in light and dark. Leger’s studio is more cluttered and eclectic by comparison, filled with a jumbled selection of formal inspiration, from a toy truck and a shoe tree to a wine bottle and one of his own sculptures.

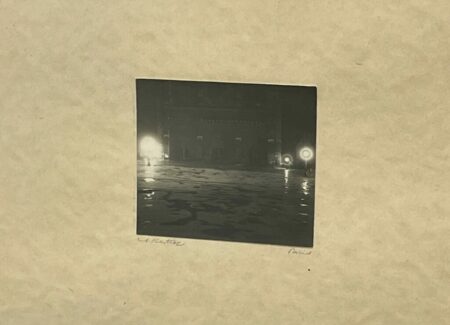

Most of the rest of the works on view come from in and around Paris, with both known and unknown images included in the mix. Of particular note is an eerie nighttime view of Notre Dame from 1925, its empty front plaza flanked by two bright lights and puddles of overnight rain. More familiar will be Kertész’ view through the clock face toward the Pont des Arts, as well as a number of images of Parisian parks, wet streets, and areas along the Seine. Another famous picture is Kertész’ well timed 1928 shot of the train viaduct at Meudon, with the passing train (and its trail of smoke) matched by a top-hatted man in the street below carrying a large parcel.

But this flourishing Paris period was soon to end. Kertész emigrated to the United States in 1936 and settled in New York, opening up an entirely new chapter in his artistic life. This show is a thoughtful summary of how his formative years in Budapest began his artistic journey, and how in the following decade or so in Paris, he expanded and distilled that photographic vision. As seen here, Kertész’s best known photographs from these early decades continue to thrill (especially as presented in lushly tactile vintage prints), and the lesser known rarities on view remind us of his consistency as a photographer, the power and sophistication of these more overlooked pictures nearly equal to some of his most iconic masterworks. As the summer rolls on and the city starts to cook, this show will provide a welcome respite from the ungainly group shows around town, its narrow slice of time and place providing more than enough raw material for Kertész and his Modernist impulses.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced between $9500 and $95000, with several marked POR. Kertész’ works are routinely available in the secondary markets, with many prints (and portfolios) coming up for sale in every season. Recent prices have ranged between roughly $2000 and $200000.