JTF (just the facts): A total of 12 color photographs, framed in white and matted, and hung against white walls (with one divider) in the main gallery space. All of the works are archival pigment prints, made between 1980 and 2001 and printed later. Each print is sized 16×20 inches, and is available in an edition of 30. (installation shots below.)

The show also includes 4 sculptures, from 1980, 1989, and 1990. Each is polyester resin casting on bronze base with patina, mounted on oval base. Physical sizes range from roughly 12x8x9 to 20x11x9 inches, and the works are available in editions of 30.

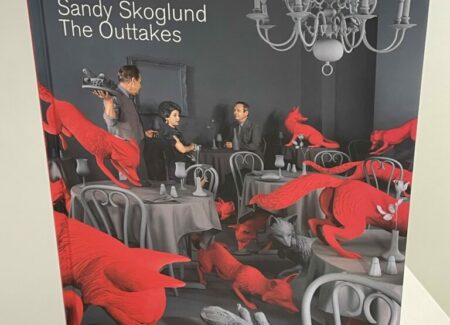

A monograph of this body of work was published in 2022 by Silvana Editoriale (here). Hardcover, 23×28 cm, 40 pages, with 30 color illustrations. (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: First drafts, variants, outtakes, and other alternate versions of well known artworks are tantalizing raw material for dedicated and obsessive fans. Process-centric remnants like these offer a refreshing mix of the familiar and the unexpected. Our awareness of the original works sets the trap – we think we know what’s coming, and can therefore easily anticipate the melody, the composition, or the story line, but then that familiarity is upended by a fresh new artistic interpretation. Perhaps a simple improvised change of notes or gestures has been included, or maybe a more fully reconfigured and reimagined artwork has been created, and so our experience of both the original and its relative is enriched and transformed, in that we can make a real time comparison between the two, and consider the choices, decisions, or rethinking that took place in between.

Photographically, it is often the case that a photographer will make multiple exposures of a single subject, particularly in the case of fast moving situations (like sidewalk street scenes) where the composition and framing are in flux. But even in more static studio setups, photographers generally make multiple images, to meticulously work through specific variants of positioning, lighting, and other details, eventually providing options for selecting the one that best captures their intent. In the pre-digital world, a contact sheet of an entire roll of film exposures was the common venue for this process of comparing, editing, and choosing, which is why they can offer so much insight into how a photographer’s mind works – we can literally watch as the artist refines a composition from frame to frame, and then see which picture was ultimately preferred over all the others.

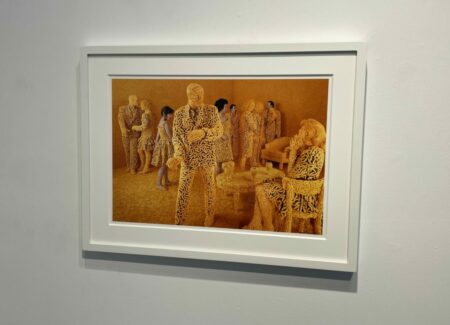

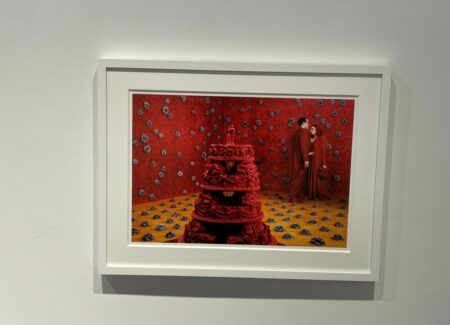

During the lockdown months of the pandemic, Sandy Skoglund went back into her archives and unearthed many of the variant images she has made during her long career. This show brings together a dozen of those pictures, each a single outtake from one of Skoglund’s best known installations, along with four sculptures of the colorful dogs, cats, and foxes that originally inhabited the scenes. Together, they partially pull back the curtain on Skoglund’s process, encouraging us to think more carefully about what it must have felt like to physically build her astonishingly elaborate setups and then to stage single frame photographic narratives inside those surreal worlds.

When Skoglund began making her installations in the early 1980s, she likely didn’t think of herself and her art as “pre” anything; today, one of the simplest, and most reductive ways to think about Skoglund is that she was gloriously “pre-digital manipulation” or “pre-Photoshop”, painstakingly hand building every eccentric detail before digital software tools and AI made such flights of fancy more commonplace. At that time, she was simply exploring the possibilities of exaggerated imagination and pre-visualized staging, and doing so by constructing rooms filled with bright color themes and fantastical scenes. And in the context of that moment in photography some four decades ago, her artworks were altogether and resoundingly original, and still are. To her credit, her playful images are easy to like; but in a backhanded twist, that very accessibility has also to some extent downplayed the conceptual rigor and sophistication that is embedded in her practice. She’s rightly known and respected as an innovator, but perhaps less so than she should be, especially by contemporary artists who are now standing on her artistic shoulders.

Looking at Skoglund’s outtakes makes clear some the aesthetic decisions she was wrestling with. (As an aside, a handy thumbnail pairing of the original/outtake versions of the scenes would make this analysis somewhat easier to envision.) Several of Skoglund’s variant selections make clear that the essential photographic question of where to put the camera wasn’t always entirely obvious, even after the installation had been fully constructed. Her original pink patio setup featuring a cloud of black squirrels placed a foreground tree trunk on the left side, but her variant choice shifts the camera right a bit, leaving that out. And her deep blue bedroom scene with floating goldfish made the fish in the foreground more prominent, while in the outtake the camera is raised, showing less floor and more ceiling (as well as the unpainted edge of the room on the left side). Skoglund gets even more radical in her revised placement choices in a variant of the jelly beans and butterflies scene, where she crops out an entire figure on the left, and the blue tiles and dragonflies setup, where the scene has been flipped left to right.

In other cases, once the stage was completed, Skoglund had choices to make about where to place the human figures, and in a few of the variants, she has opted for quite different narratives. In her white popcorn scene, in the original, a man carries a woman toward a campfire with a man and two popcorn figures huddled around it; in the variant, the two have arrived and sat down, the woman now touching the shoulder of the previously seated man, and the other man sitting back a distance. It’s as if several moments of time have passed between the two frames, and the implied or possible relationships between the people have shifted. The same might be said of the red foxes in the restaurant scene, where in the original the diners have already been served their drinks by the waiter, and in the variant, he is still walking toward the table with his tray, the apparent time in the setup rewound just a few moments.

Most of the rest of Skoglund’s variants are more subtle in their differences from the originals, with slight changes to poses, gestures, movements, and the position of figures in relation to one another. Two worth noting are the more gracefully nearby nudes in the eggs and snakes bathroom scene, and the much closer couple in the red cake room, in each case the connection between the figures has been made more intimate. This is reversed in the variant of the green living room filled with blue dogs, where the original had the couple near the fireplace sitting and touching each other, while the variant has her standing up a bit further away, creating some distance and separation. The other outtake images are even more nuanced, with the turn of a head or a deeper look into the freezer changing the mood of the moment ever so slightly.

Seen as a group, Skoglund’s outtakes make her seemingly static installations come alive with possibilities, more like settings for stage plays or self contained environments than carefully orchestrated photographic instants. Fables and fairy tales spin out from each fanciful location, and the sculptural animals become characters in and of themselves rather than frozen decoration. I came away understanding that “built to be photographed” need not necessarily be limited to a one time photographic event, but can instead be the starting point for different kinds of visual narratives. The variants expose a deeper richness and resonance than I had previously imagined, each photograph actually a window into an entire world.

Collector’s POV: Both the photographs and the sculptures in this show are priced at $7700 each. Skoglund’s work has been intermittently available in the secondary markets in the past decade, with recent prices ranging from roughly $3000 to $40000.