JTF (just the facts): A total of 32 large scale black-and-white photographs, generally framed in black and unmatted (smaller prints are matted), and hung against white and dark grey walls in the main gallery space and the entry area. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- 7 gelatin silver prints, 2005, 2014, 2016, 2019, sized 20×24 inches

- 5 gelatin silver prints, 1998, 2009, 2016, 2018, sized 24×35 inches

- 5 gelatin silver prints, 2016, 2017, sized 35×47 inches (or the reverse)

- 8 gelatin silver prints, 2009, 2018, 2019, sized 35×53 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 2016, sized 53×39 inches

- 2 gelatin silver prints, 2016, 2017, sized 47×63 inches (or the reverse)

- 2 gelatin silver prints, 2009, 2017, sized 71×47 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 2005, sized 60×80 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print, 2019, sized 60×90 inches

The prints are available in open editions. Larger and smaller sizes are also available for all the images.

A monograph of this body of work was published in 2021 by Taschen (here). Hardcover, 14.1 x 10.2 inches, 528 pages.

Comments/Context: For most of the people who use a camera to see and document the world, the words “photographer” and “artist” usually suffice to describe their role or professional status. And for those in particular who use photographs to communicate news and tell visual stories for various publications, the word “photojournalist” can be a more specific definition for what they do. But for Sebastião Salgado, while all of these words apply to his work, none quite does justice to the breadth and intent of his photographic activities, and so we often find “activist”, “adventurer”, and other descriptive words appended to his lengthy photographic biography.

For the most recent decade or two of his photographic career, Salgado has focused his attentions on the visual preservation of the natural world, traveling on expeditions to the literal ends of the Earth to photograph endangered lands, animals, plants, and human populations. His ambitious 2014 project Genesis (reviewed here) was his first foray into making climate change and its diverse effects a central focus, and his efforts took him to various continents and ecosystems to document the rapidly changing world, putting particular emphasis peoples, places, and things that were disappearing at an alarming rate.

While the Brazilian photographer has been traveling to the Amazon region since the 1980s, and Genesis included some images made there, his newest project Amazônia narrows his attention to the indigenous tribes and their local environments there, with a flurry of new images made on trips and expeditions in the past decade or so. Between mining and oil drilling operations, illegal logging and broader deforestation, wildfires, agriculture and cattle farming, and more general roadbuilding through the forests, these ecosystems and ways of life are clearly in peril, and Salgado’s photographs attempt to capture the majesty of these biodiverse places, so they can be further protected before they are irreparably damaged.

Salgado’s aesthetics have become increasingly extreme over the years, pushing standard gelatin silver prints to wider ranges of light and dark contrast, effectively giving up some middle grey tonal richness in exchange for increasing the blown out drama of the scenes. Ansel Adams was known to employ similar techniques in some of his landscapes, adding layers of moody grandeur to his views of Yosemite and elsewhere with careful darkroom manipulations; Salgado has taken those lessons and intentionally amplified them several steps further, making many of his images feel almost dreamlike and surreal. To my eye, Salgado walks a knife edge with this aesthetic approach – when it is most successful, the images feel symphonic and operatic in their natural grandeur, but when he pushes too far, which he does often enough to be noticeable, that artificial theatricality feels forced and pompous, the amplifications drawing attention to themselves and unintentionally undermining the inherent force and awe of his compositions.

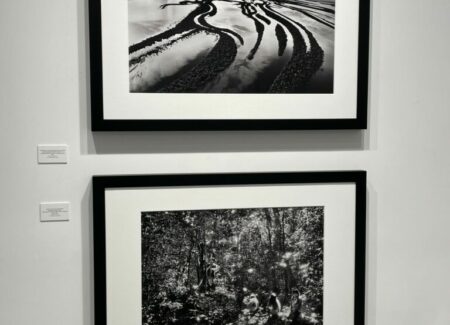

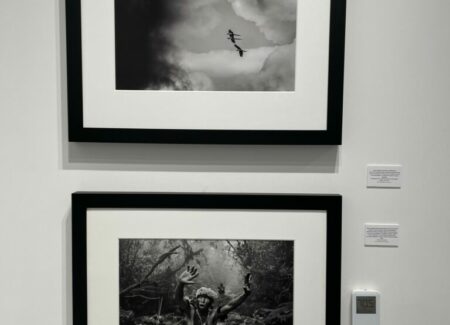

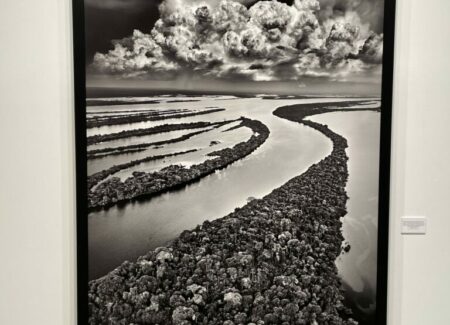

Many of Salgado’s most dramatic Amazon scenes have been taken from elevated positions or from the air. Looking down on seemingly untouched expanses of dense forest, river valleys, and sweeps of terrain, the images often balance the land with massive cloudscapes in the skies (and even one rainbow), creating pairings that alternately feel ominous and glorious. From above, the rivers turn into ribbons of light that twist and turn through the textured darkness of the jungle, with delta areas mixing rippled (or flat) water and dark sandbars into striped patterns. Some of the cloud formations Salgado has documented are toweringly astonishing, and when the contrasts are further heightened, the implied power of the weather systems is even more thick and imposing, almost to the point of caricature. The strongest of these broad landscape compositions delivers a punch of irreplaceable natural wonder, without feeling so exaggerated that we lose our willingness to go along with Salgado’s poetic license.

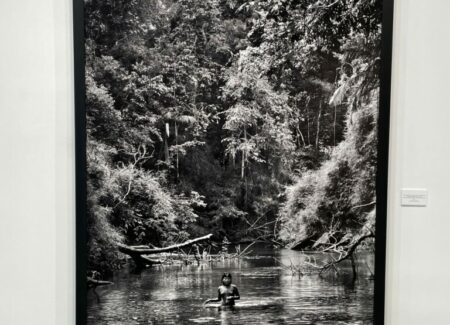

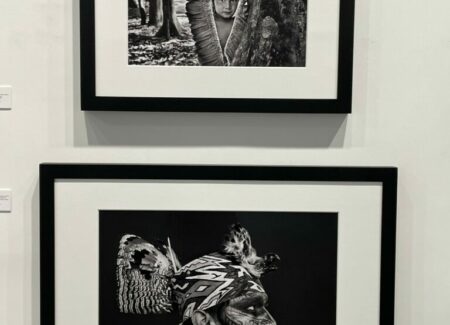

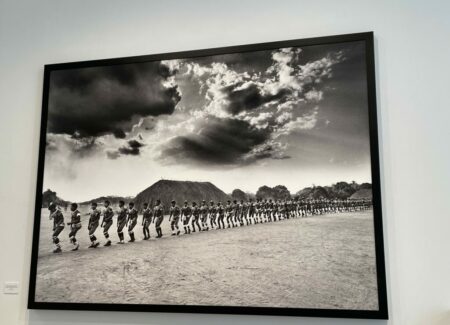

At the other end of the scale and grandeur spectrum are much more intimate portraits of indigenous peoples and their various daily rituals, as seen from close up. Salgado spent time with the Yanomami, the Yawanawá, and the Zo’é, among others, building up enough trust to be allowed to be present at everyday events like fishing, bathing, and simply resting, in addition to special occasions and rites of passage when decorative clothing and body paint were in use. A massive print of a marching line of warriors dominates one wall (over the reception desk), but many more of the images of daily life are less imposing. A pair of silhouetted figures paddle along at daybreak, a young woman bathes in an edenic stream, and families fish in canoes underneath the backdrop and overhang of the enveloping forest. Salgado also brought along a makeshift studio setup, where he made isolated portraits against black linen. His portraits, several of which are installed along a dark grey wall, are unexpectedly beautiful, almost disconcertingly so, with penetrating stares doused in dark makeup and elaborate feathered headdresses surrounding intricately painted faces. Of course, some of these pictures edge towards a “noble savage” trope, but again, the strongest pictures of people resist the urge to make the images unusually dramatic, leaving some mystery and magic in the gestures and shadows.

Many of Salgado’s in-between photographs revel in textures discovered in the landscape. Some feature palm leaves and trunks seen up close and washed to tactile patterned contrasts. Others use rivers and lagoons as the host for eye popping reflections and doublings. And still others encourage the amplified contrasts to dissolve into graininess, which takes on expressive qualities in the rain, or almost Impressionistic painterliness when seen in ripples of water or misty fogs.

My overall response to Salgado’s Amazônia was meaningfully conflicted. On one hand, I was successfully seduced by many of his magnificent natural landscapes and precious textural specimens, and I appreciated his ability to communicate their beauty and their perilously endangered value; on the other, I was often turned off by his too muchness, and his instinct to push something understated and lovely into something overwrought and bombastic, as if we couldn’t appreciate the scenes without a dose of visual exaggeration. As I walked through the galleries, I was pushed and pulled, both entranced and somehow annoyed by his overt attempts at emotional manipulation. Perhaps a slightly different edit of the material might tone down some of this aesthetic gamesmanship and forefront some of the images that revel in more depth and nuance. It feels like Salgado’s head and heart are in the right place, and in many ways, he’s found a plausibly workable approach to the problem of documenting a natural world threatened by climate change in a way that the public at large will embrace and understand. If only he had an editor who would pull him back now and then from his most affected and mannered aesthetics, I think we’d better feel the collective urgency he’s trying to communicate.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show range in price from $11000 to $100000, based on size, with additional smaller and larger sizes available at a range of prices. Salgado’s prints are routinely available in the secondary markets, with recent prices ranging from a few thousand dollars (later prints, in large editions) all the way up to $126000.

After similar misgivings I now wonder if it is specifically the massively over-blown photographs that are likely the important pictures in this show, and everything much else less so and perhaps rather safe.

I somehow anticipate that Salgado’s brutal Jungian vision of jungle, coiling river and mad, boiling sky will be waiting for me when I sleep tonight. I sense his compression of light and dark has punctured some membrane that separates one world from another, apt in more ways than one.