JTF (just the facts): A total of 24 album pages with black-and-white photographs, along with another 31 black-and-white photographs, all framed in black and matted and hung against light grey/orange walls in a series of 3 connected gallery spaces on the second floor of the museum.

The following works have been included in the show:

Berenice Abbott

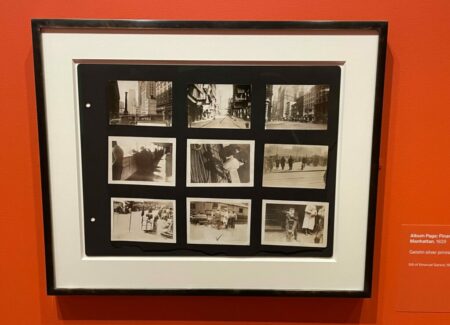

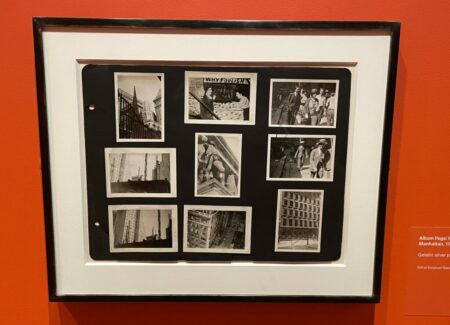

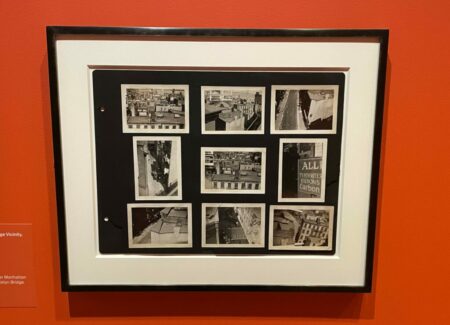

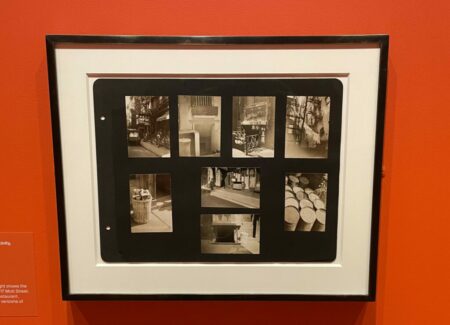

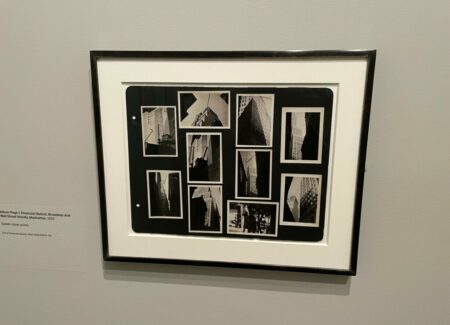

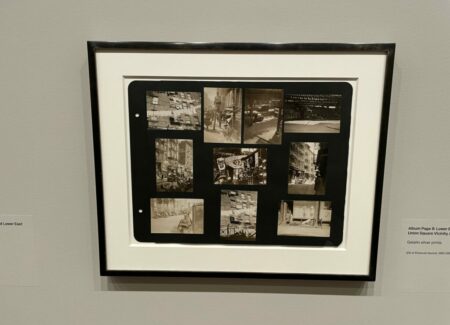

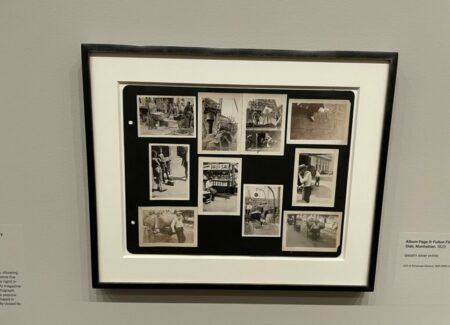

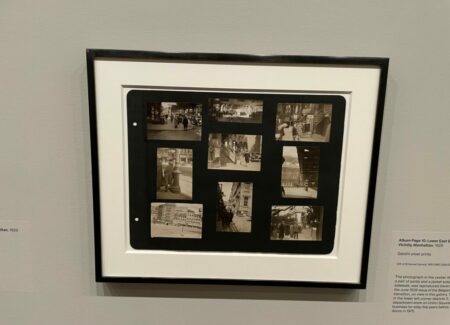

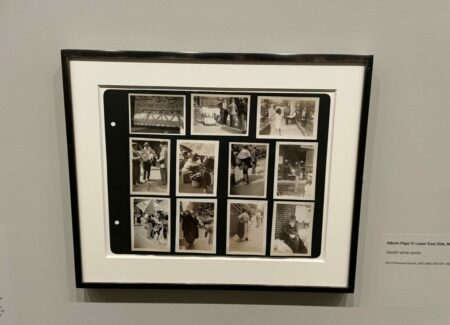

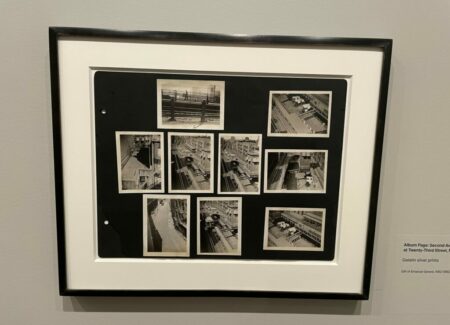

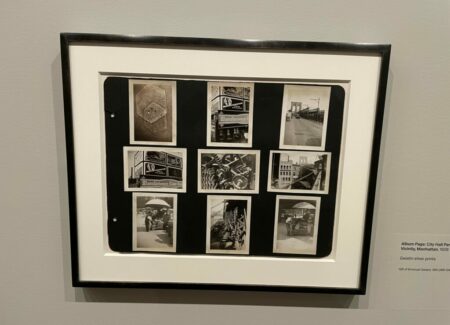

- 24 album pages, with 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, or 12 gelatin silver prints each, 1929

- 5 gelatin silver prints, 1925, 1926, 1926-1927, 1927, 1929

- 12 gelatin silver prints, 1935, 1936, 1937, 1938

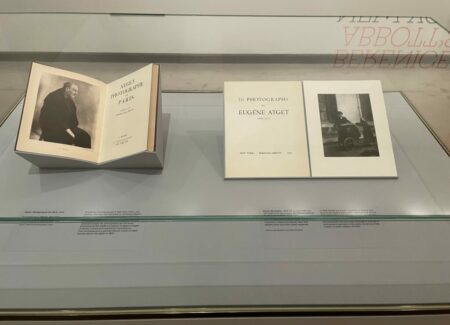

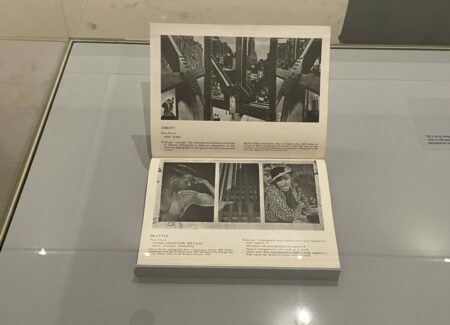

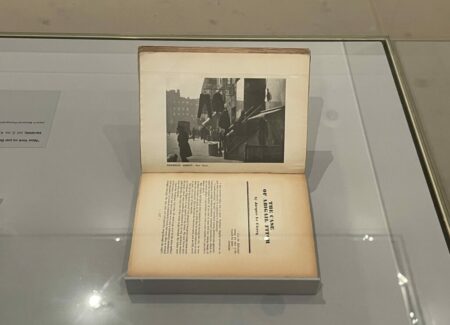

- 1 image in photobook, 1932 (in vitrine)

- 1 image in photobook, 1929 (in vitrine)

- 4 images in magazine, 1929 (in vitrine)

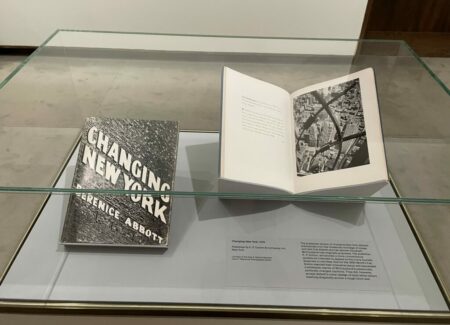

- 1 photobook, 1939 (in vitrine)

Eugène Atget

- 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, c1910

- 6 gelatin silver prints from glass negative, 1912, 1922, 1925, 1926, 1927

- 1 photobook, 1930 (in vitrine)

- 1 portfolio (printed by Berenice Abbott), 1956 (in vitrine)

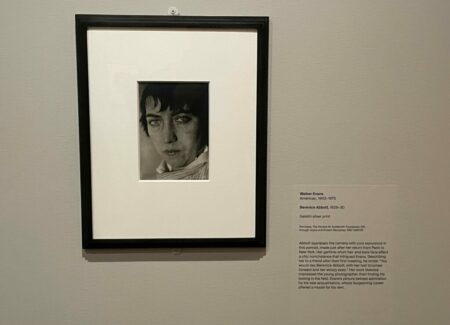

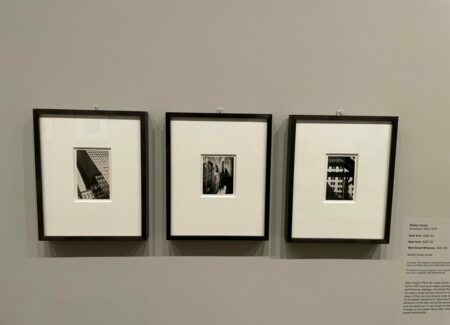

Walker Evans

- 4 gelatin silver prints, 1928-1930, 1929-1930

Paul Grotz

- 2 gelatin silver prints, 1928-1929

Margaret Bourke-White

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1930-1931

(Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: Over time, the narratives we tell about well-known artists naturally tend to get simplified down to a stream of key projects and most important works, with the messiness of the actual in-between artistic journey conveniently left out. In the case of Berenice Abbott, her story is usually centered on her now iconic “Changing New York” series from the late 1930s, and if that story is then expanded a bit, her earlier years in 1920s Paris, where she worked for Man Ray and befriended Eugène Atget, tend to be the next chapter added. If we then decide to go even deeper, still other artistic chapters in Greenwich Village in the early 1930s, at MIT in the late 1950s, and much later in Maine can be bolted on to Abbott’s story if we are building up a fuller career arc.

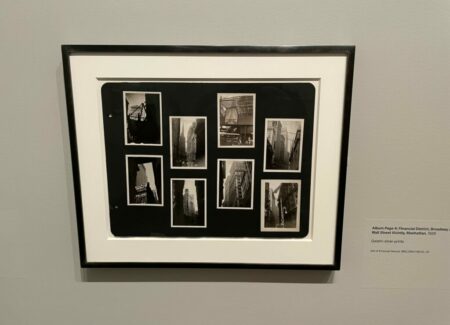

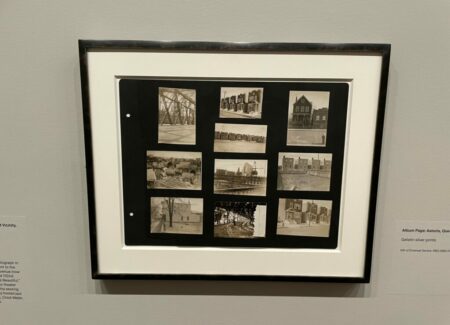

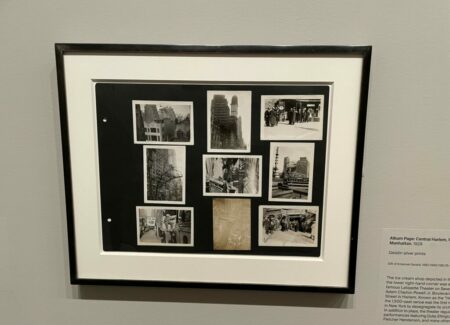

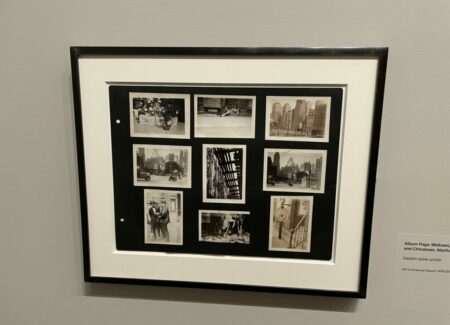

This small show slips into one of the transition zones in Abbott’s artistic life. In 1929, Abbott came back to New York after eight years in Paris, and was almost immediately transfixed by the city. Using a handheld camera, she wandered the city’s streets and neighborhoods, jotting down “photographic notes”, which she then pasted into a standard black-paged photo album and arranged by location or subject matter. Ultimately she filled 32 pages in this album, covering ground from the Financial District and Chinatown to Harlem and Astoria. Abbott would later switch to a large format camera for her “Changing New York” pictures, so this album represents an early set of looser and more improvisational urban experiments, and a testing ground for ideas and compositions she would refine later.

Somewhere along the way, Abbott’s album was unbound, and the Met acquired groups of the pages in the 1970s and 1980s, ultimately recreating the exact order of the first 11 pages, with another 13 pages saved but their original sequencing lost. So this small show offers us a window into roughly two-thirds of the album, each page densely filled with between 7 and 12 individual prints. These framed pages have then been surrounded here by a range of other works that provide some additional context to Abbott’s 1929 album: earlier pictures by Atget and Abbott, New York city photographs made at roughly the same time by Walker Evans, Paul Grotz, and Margaret Bourke-White, and a selection of Abbott’s later photographs from “Changing New York”. But it is the album pages that are the star of this show, particularly because they offer a look at Abbott’s eye as she was re-acquainting herself with the visual rhythms of New York.

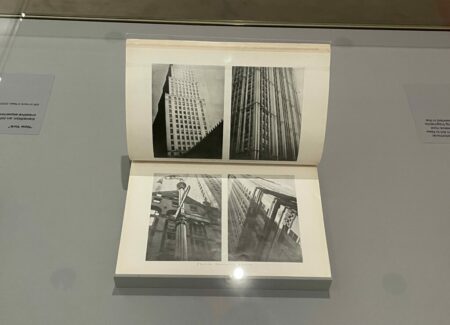

The first page of the album finds Abbott down in the Financial District, around Broadway and Wall Street, looking up at the tightly clustered buildings and urban canyons that would later feature in some of her most famous images. Steep angles and contrasts of light and dark seem to have captivated her, with looks upward using sharp building edges to frame the empty sky above. Dark buildings loom in the foreground of many of her pictures, creating crisp geometries, which she then balances with lighter buildings, construction cranes, and facades patterned by windows. She tests different weights for the various compositional pieces, and even tries an image through some ornate ironwork, a motif she would use later in a picture titled “City Arabesque”.

Several other album pages collect imagery from this same neighborhood, with Abbott reframing the available buildings in alternate ways. Some of her compositions use dark black forms on both sides of the frame, or narrow the available crack of sky down to the smallest possible size. She tries jutting flagpoles, lamp posts, and construction framing as visual interruptors, and then steps back to look at the textures of various skyscrapers, with their lines and grids of windows drawing our eyes upward, but always at an angle. Abbott nestles Trinity Church between encroaching lines of buildings, looks up at carved statuary, watches pedestrians passing by in a bustle, and climbs up to rooftops to look down with unusual steepness, restlessly trying to reconfigure the visual elements.

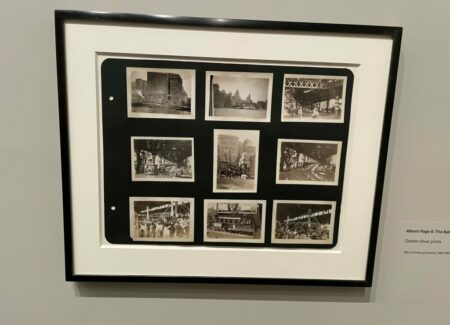

The elevated train system was another favorite subject for Abbott, and several of the album pages follow the tracks and use the station platforms as locations for photographically looking around. Underneath the tracks, she played with patterning using the crosshatched girders and the striated shadows on the streets below. At street level, she looked up at staircases and angled platform architecture. And on the platforms, she looked down the lines of the tracks, peered over the railings to the sidewalks below, and narrowed in on interruptions of light and dark that she flattened into one plane. The train infrastructure seems to have provided an endless supply of geometries to twist and reorient, as well as plenty of elevated vantage points to abstract the city into simpler forms.

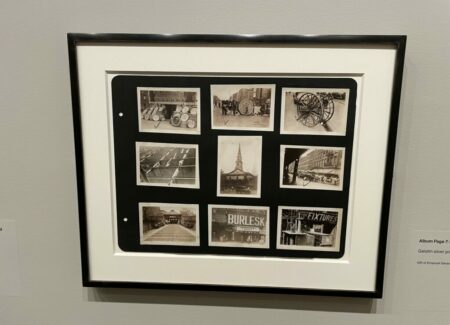

When Abbott ventured down to the Lower East Side and Chinatown, she tended to stay at street level, and the album pages from these neighborhoods feature many more images of streets, tenements, storefronts, and local residents. Lines of fluttering white laundry strung from the windows and boldly lettered signage caught her eye again and again, but like Atget before her, she was drawn to the shop windows, storefront displays, and traditional vendors selling merchandise from carts. Images of stacks of tires and barrels of spices are filled with repeating patterns, and mannequins behind glass offered familiar opportunities for found surrealism. One album page is filled with mostly street portraits, where Abbott was singling out individuals from the larger crowds. Other pages offer small discoveries: a man on stilts, huge wheeled carts, shoeshine boys, barbecued ducks hanging in a restaurant window, vendors working under umbrellas, and below-ground basement shop entrances, each visually unexpected.

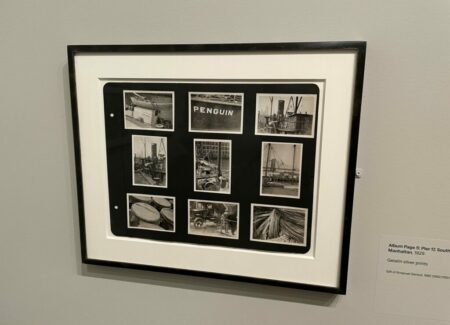

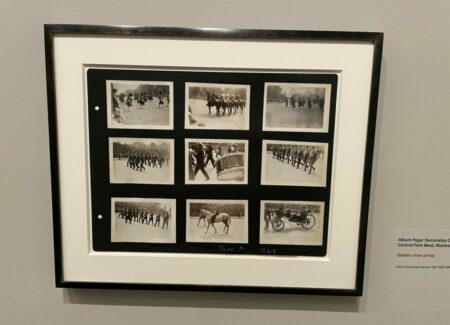

Abbott’s album pages from the Battery, South Street Seaport, and the Fulton Street Fish Market briefly step away from urban subjects and take in life along the city’s docks and piers. Boats, masts, and rigging were an obvious subject, as were the tugboats set against the city skyline, but Abbott sees them with freshness, pulling on angles and seeing through rope lines. On the docks, she narrowed in on piles of barrels and metal hoops, and at the market, cranes and weights dominate her compositions. And still other album pages were dedicated to various other city sights and unexpected finds: a parade in Central Park, painted advertisements on brick walls, row houses in Queens, patterned manhole covers, and even the Brooklyn Bridge.

What these album pages show us is an Abbott unencumbered by the slowness and formality of a large camera, where the voraciousness of her visual curiosity was allowed to roam more freely. Like the photographic equivalent of sketchbooks, the album pages are full of trial and error, of photographic risks taken, and of ideas tried out, and as a backdrop for what we know would come later, they are a treasure trove of first drafts, with vantage points, compositional alignments, and subject matter all being tested out. While there are fewer standout images buried in these pages than we might have guessed, it’s almost as if Abbott wasn’t looking for the singular picture (or two) on these city wanderings, but was instead actively trying to get her arms around a larger aesthetic perspective which she could then refine later. Each day was a kind of photographic workout, building her muscles and getting stronger, with the map of “her” city becoming clearer with each neighborhood visited.

In this way, the power of this show lies in process rather than product – what is on view is Abbott’s approach to seeing the city, and her meticulous documenting, mapping, and ordering of her impressions. Seeing these albums, it is clear to conclude that “Changing New York” as we know it just doesn’t happen without all of this preliminary work – the aesthetic lessons she learned on these ambling photographic walks became the foundation on which she constructed the subsequent landmark project. These album pages show us her ideas assembling and coalescing, her raw visualization of the city offering her possible clues and potential pathways for how to ultimately see it with more clarity and precision.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum exhibition, there are of course no posted prices. Aside from these unique album pages, Abbott’s work is consistently available at auction, with dozens of prints coming up for sale in any given year, with prices ranging from roughly $1000 to $90000.

Thank you so much for your thoughtful and engaging review of the exhibition! So little has been written about the album, it’s wonderful to see the work through someone else’s eyes.