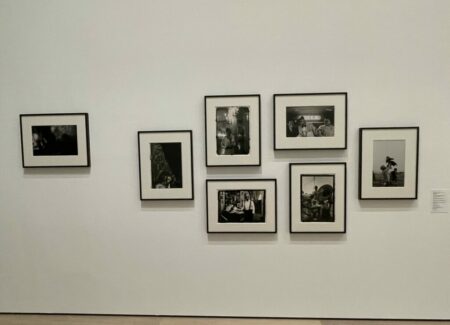

JTF (just the facts): A total of 52 black-and-white photographs, most framed in black and matted, and hung against white walls in a single room gallery space on the ground floor of the museum. The exhibit was organized by Oluremi Onabanjo and Thelma Golden, with assistance from Kaitlin Booher and Habiba Hopson.

The following works have been included in the show:

- 15 gelatin silver prints, 1972, 1979, 1981, 1985, 1987, 1989, 1991, 1992, 1998, sized roughly 12×18, 18×12, 12×19, 13×18, 18×13, 13×19, 19×13, 14×19, 19×14, 20×14 inches

- 17 pigment prints, 1973, 1974, 1976, 1979, 1980, 1981, 1989, 1990, 1991, sized roughly 12×18, 18×12, 13×18, 18×13, 13×19, 19×13, 19×14, 20×14 inches

- 2 oil paint on gelatin silver prints, 1978, 1998, sized roughly 18×12, 19×13 inches

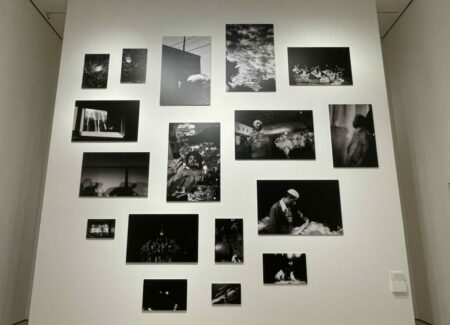

- 17 UV prints on Dibond, 1972, 1972/1991, 1977, 1978, 1980, 1981, 1985, 1991, sized 16×24, 24×36, 36×24, 40×60, 60×40, 47×72, 72×47 inches

- 1 vinyl wallpaper, 1980, sized roughly 148×262

(Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: The positioning of Ming Smith’s current show at the Museum of Modern Art walks a very delicate line. MoMA was the first institution to purchase Smith’s work back in 1979, but its support of Smith and other Black photographers of her generation in the intervening years since has been decidedly uneven. Coming on the heels of the successful survey show of the Kamoinge Workshop photographers (of which Smith was the first female member), and gathering interest in Smith’s work in particular, in the form of a run of gallery shows, art fair booths, and a monograph in the past few years, this MoMA exhibit is carefully billed as a “critical reintroduction” of her work.

As I read that phrase, I thought about alternate ways to think about those precise words – “critical” as in thoughtful and scholarly, “critical” as in urgent or overdue, and “critical” as in perhaps the institution examining itself and finding its own history wanting, with “reintroduction” offering room for a fresh eyes interpretation of her work as well as an acknowledgment that there will be some who will have been paying close attention to Smith all along. While any such MoMA show is of course an occasion to be celebrated for the artist, there is an undercurrent of lingering awkwardness here (on the museum’s part, in the form of missed opportunities in the past), that gives the proceedings a hint of finally fixing something that was long ago broken.

Starting to the left of the introductory wall text, this exhibit lays out Smith’s work in a distinct progression, telling her artistic story in a slow circle around the room. It begins by rooting us in Smith’s subtle vision of everyday Black life in Harlem, where people alternately hang out on front stoops, look out apartment windows, walk along the streets in groups, participate in protests with raised fists, and pass the collection plate in crisp whites. In this world, a connective sense of Black history is never far from view – in the neon sign of the Apollo Theater, in Duke Ellington’s face on the television, in the persistent memory of an African burial ground, in the stern pall bearers carrying Alvin Ailey’s casket, and in the face of James Baldwin seen like a benevolent ghost hovering above in the clouds of a darkening Harlem sky.

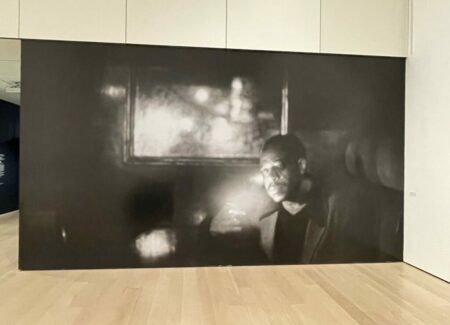

Many of these images have the straightforward aesthetics of documentary imagery, bringing a sense of personal immediacy and authenticity to Smith’s choices. But Smith really shines when she lets loose her more impressionistic side, where deliberate blurs, shadows, and drifts of light transform her moments into something more elusive and ethereal. This vision powerfully captures the fleeting invisibility of the Black experience, glimpsing figures that disappear and dissolve rather than coalescing into clarity. Nighttime images punctuated by the flare of streetlights offer moody views of a shiny hubcap passing a local dry cleaner and the striding stick figure of a man, the moments partially erased and approximated into expressive slices of feeling. Even more poignant is a photograph titled “Invisible Man, Somewhere, Everywhere”, with a Black man trudging through the gloomy city, his struggle seemingly overlooked by the indifferent world around him.

This particular gallery space features a towering middle wall, which the curators have filled with a salon hanging of unframed enlargements, where Smith’s interest in the properties of photographic light ties together a range of subject matter studies and portraits. Some of the strongest works see various jazz musicians as anonymous squiggles of light or multiplied shadows, the improvisational energy of the music seemingly captured by Smith’s lens. Other images of Arthur Blythe and Sun Ra add a more cosmic element to the proceedings, the figures surrounded by pinpricks of light like stars. And when Smith turns her camera toward the movements of dancers, she lingers on moments of collective joy and spirituality, where ensembles jump with contagious abandon or raise their hands in solemn praise.

Smith’s introspective side also comes out on this huge wall, in understated works that turn inward with quiet but surprisingly compelling intimacy. Smith’s iterative moonlight studies seem related to Kikuji Kawada’s similar looks skyward, and her images of windows and ephemeral transparent curtains have even more nuances of atmosphere and aspiration to share. The pairing of “Roxbury Interior, Boston, MA” (from 1978) and “The Window Overlooking Wheatland Street Was My First Dreaming Place” (from 1979) provides a lovely point and counterpoint – one image taken from the inside, where darkness surrounds and envelops the softness of the closed window, and another where the window is opened, and the framed glass provides both a reflection of the scene outside and a separation from the curtains inside. Both pictures are resonant in their sense of place, and in the significance that those windows had as representations of portals to something larger.

Much of this stylistic experimentation is toned down in a selection of images from Smith’s series “August Moon for August Wilson,” seemingly traded for a more modest kind of lyrical understatement. There is certainly sinuous grace to be found in the movement of pool players, and honest endurance is etched on the faces of families on the bus and ordering at a diner, and Smith celebrates these small human stories. Her framing of a woman in the kitchen through the opening in a cupboard is particularly smart, blocking us with domesticity but leaving us a space to make a connection.

After a short interlude of Smith’s worldly visual experimentation, that jumps from from Egypt (in a shifting double exposure) and Japan to France and back to the exuberance of the West Indian parade in Brooklyn, the show wraps up with an eclectic gathering of Smith’s documentation of Black accomplishment. Composer Edward Boatner is seen standing near his piano and surrounded by faces from the past. US Representative Eleanor Holmes Norton and activist Dorothy Height warmly share the crowded back seat of a car. Jazz musician Charles Mingus poses with kids in a New Orleans brass band. And dancer and choreographer Judith Jamison stands with regal grandeur near an ornate mirrored wall. These high points are then matched by the simple joy of a man tossing his infant into the air, the loving flight supported by the supportive tenderness of his outstretched arms, the measurement of success coming in many forms.

As curators and scholars dig deeper into Smith’s archives, unearthing more and more of her long and winding artistic story, it is my hope that Smith’s more expressive tendencies will come to the forefront, as it is some of these original aesthetics that separate her most clearly from her contemporaries. This show delivers an engaging mix of the known and the unknown, and ably provides the tightly-edited “critical reintroduction” it claims as its goal. Smith still needs to be better slotted into the ever-evolving arc of 20th century photography history, but likely that broader re-appraisal challenge – one that brings many of the key photographic voices that were previously overlooked or marginalized back into a more inclusive and multi-faceted conversation – is already taking place behind the scenes.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum exhibition, there are of course no posted prices. Smith’s work is represented in New York by Jenkins Johnson Gallery (here) and Nicola Vassell Gallery (here), where she had a solo show in 2021 (reviewed here). A monograph of Smith’s work was also published by Aperture in 2020 (reviewed here). Her work has little consistent secondary market history, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.