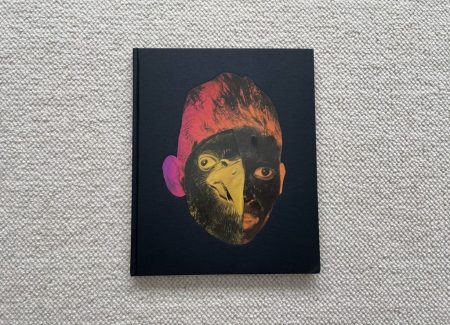

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2020 by Chose Commune (here). Hardcover (24.5×30 cm), 136 pages (40 shorter in width), with 80 color reproductions of photographs and collages. Includes a poem by Meena Kandasamy and a list of plates with locations and dates. In an edition of 1000 copies. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: While many contemporary photographers move from one project to the next iteratively, sporadically, or even improvisationally as the case warrants, Vasanatha Yogananthan has instead settled into a long term rhythm that feels resolutely methodical. Using the story of the Ramayana as a foundation, he has spent the last half dozen years slowly working through the framework of the narrative, re-interpreting each chapter of the ancient Indian epic through photography. The overall effort will ultimately stretch to seven discrete projects gathered together under the title A Myth of Two Souls, with each one published as its own stand alone photobook. The sequence began in 2016 with Early Times (reviewed here), and has since continued step-wise through The Promise (reviewed here), Exile, Dandaka, and Howling Winds in the subsequent years.

Along the way, Yogananthan has liberally experimented with different modes of visual storytelling. He has mixed straight documentation with staged scenes, added traditional overpainting and cartoon inserts, and deliberately wandered back and forth between a literal following of the text and more allegorical, metaphorical, and allusive responses to the events of the famous story. To date, it has been an impressively consistent effort, with each successive chapter finding its own artistic voice while still keeping a measure of continuity with its predecessors. Afterlife is the sixth book in the series, and in many ways, yet again pushes out into uncharted artistic territory for Yogananthan.

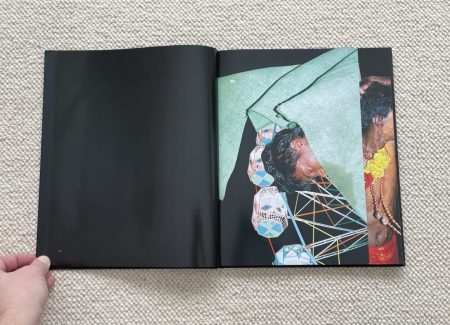

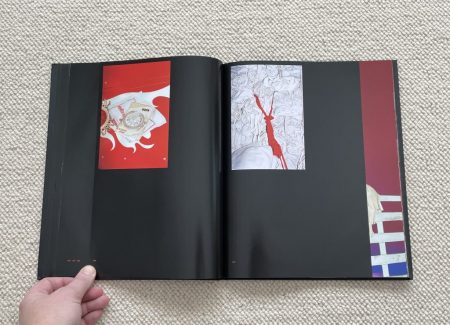

This part of the story centers on the war between Rama and Ravana, fought over the kidnapping of Rama’s wife Sita. And while battle, wars, and archery/sword fighting in particular might have offered Yogananthan plenty of artistic options, Afterlife takes a decidedly atmospheric approach to representing the disorienting struggle. The cover of the photobook immediately tells us we’re in for something different than before – it’s entirely black, except for a tipped in collage that splits a head in half, combining a blackened face tinted orange and pink and a bird mask. Perhaps offering us the dualities of life and death, good and evil, or the two sides in the aforementioned war, it’s a far cry from direct documentation, however expressively defined.

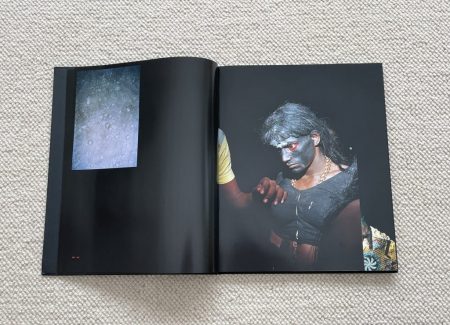

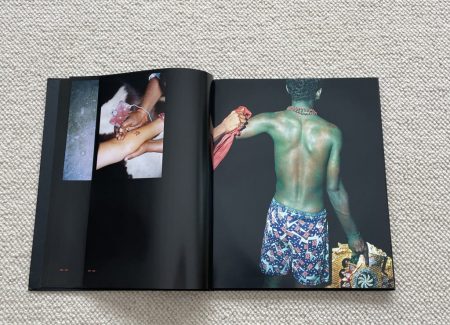

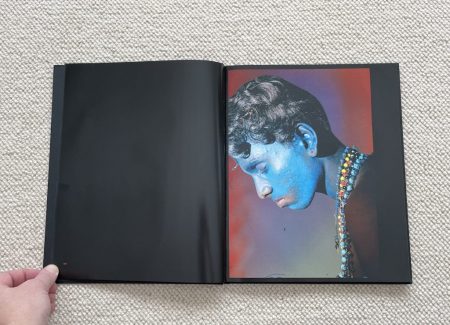

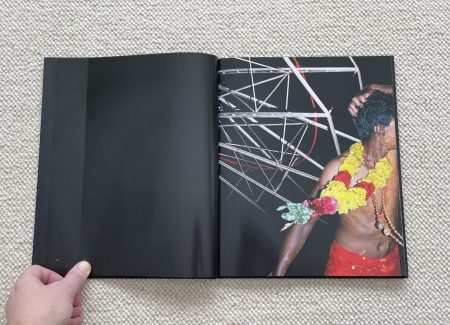

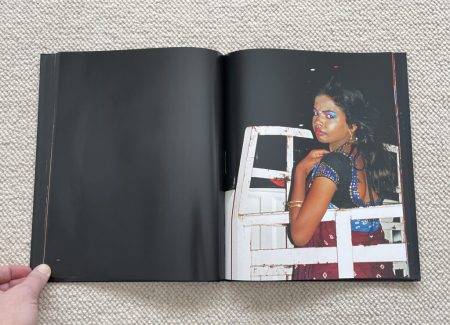

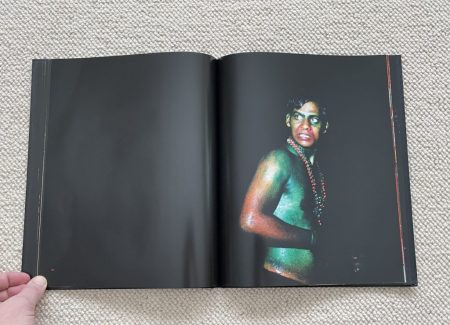

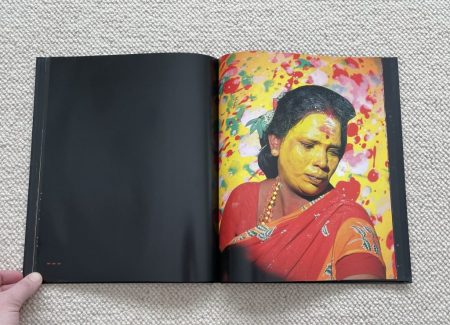

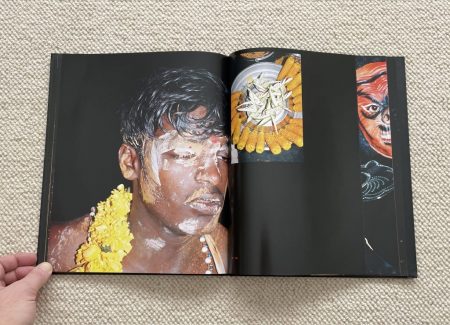

Thick, enveloping darkness is the dominant motif of the photobook, stretching from the covers and endpapers through glossy black pages and images that turn the surrounding night into a flat void. And for the first time, Yogananthan has actively used flash, the brightness of the light amplifying the colors in his photographs, sometimes to the edge of harsh, vivid, almost surreal saturation. Set against the darkness, his pictures take on a sense of dramatic theatricality, where emotions have been heightened to the breaking point.

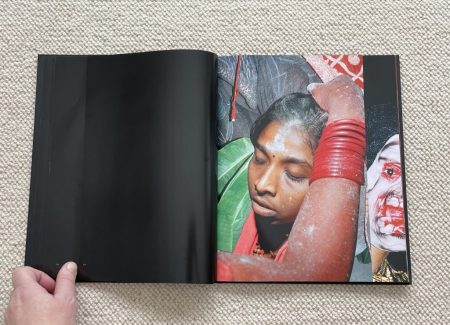

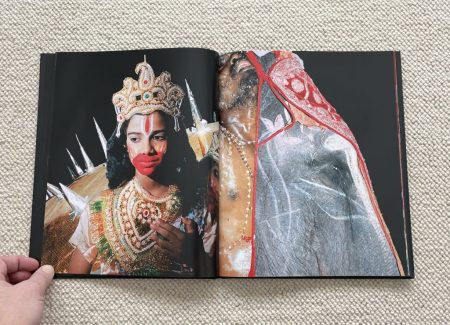

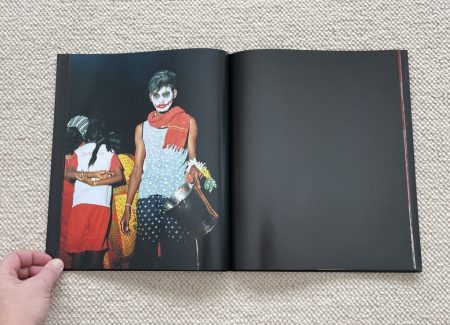

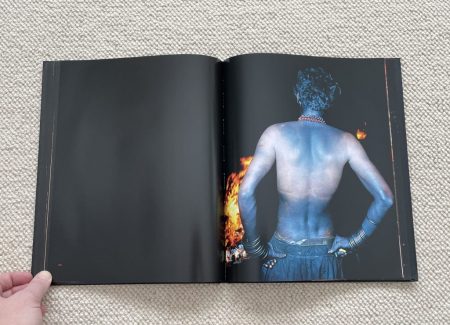

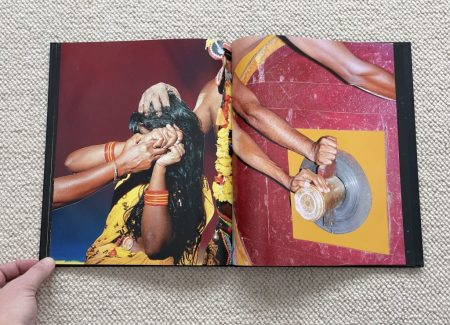

Rather than show us the war between Rama and Ravana as a physical struggle, Yogananthan turns it into a mental battle. Using the festival of Dussehra as his ostensible subject, he looks away from the obvious ceremonies and attractions and instead points his camera at the revelers. With painted faces and bodies, and dressed in elaborate and sometimes frightening costumes, they work themselves into a frenzy, trying to achieve a trance-like, ecstatic state. It is these moments of internal struggle that Yogananthan is after, and his pictures show us a parade of glassy-eyed stares, blank expressions, and hazy out-of-it faces, each person trying to find an elusive moment of grace.

Like war, this set of encounters is often harrowing. Faces are painted black with red eyes, bodies are covered in beads and flowers, and beaded headdresses make some look like gods and goddesses themselves, and the personas get even more frightening as ghoul masks, fake machetes, thick strands of black hair, and costumes made of rags take over. And while the faces and expressions tell much of the story here, Yogananthan is also very much aware of the gestures of touch and embrace. Hands reach in to gently dab foreheads with paint, heads lean in to momentarily touch, and arms grapple, make music, and rise up in ballet-like floating movements, all with a sense of collective tenderness and subtlety.

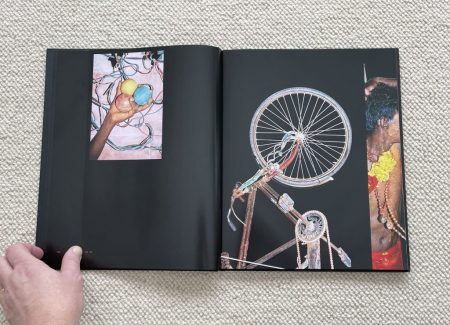

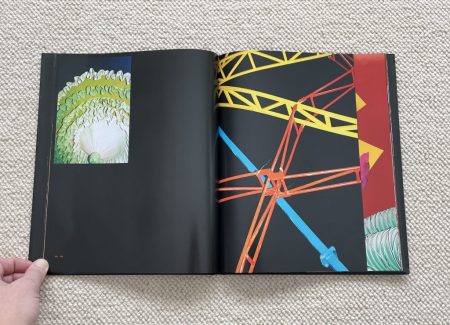

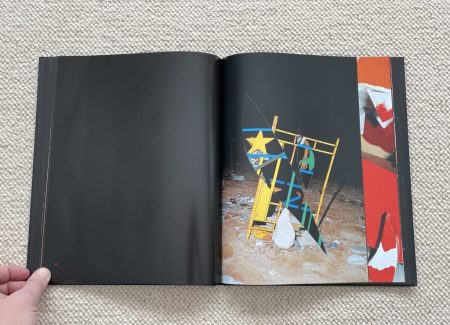

Still life images provide context for these dream-like visions, turning the obvious ever so slightly toward the perplexing. A clock stuck at midnight opens Afterlife, letting us know the witching hour has begun. Carnival infrastructure, like the metal struts and enclosed cars of rides, and stripes of electrical wires create geometric patterns against the blackness, and treats like fried dough and corn on the cob are similarly arranged in neat patterns. In Yogananathan’s hands, elephant skin turns mysterious, an old bicycle rears up like a totem, and a rip in a patterned tapestry might just offer a door into another world.

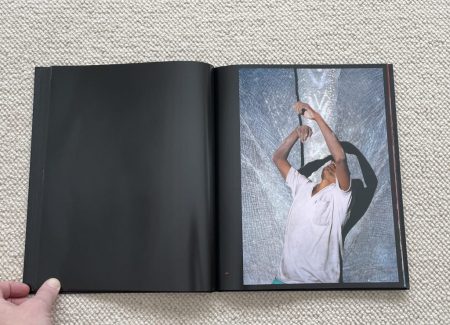

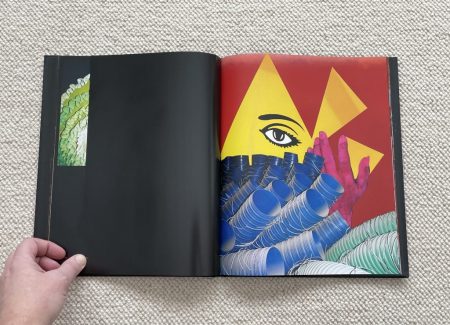

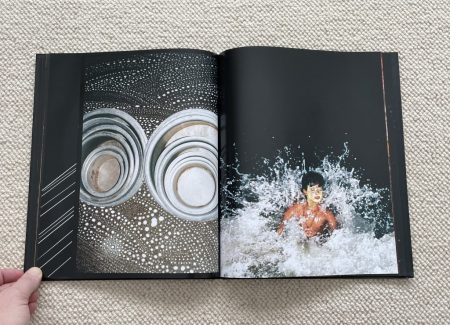

If all of this bright visual electricity wasn’t enough to disorient us, Yogananthan goes one step further in a selection of collages that are intermingled into the visual flow of the photobook. Using straightforward cutout techniques, he replaces backgrounds, layers images, and creates unlikely pairings, confusing our sense of reality. In one composition, a boy with a painted face looks dazed as he spins within a maelstrom of what might be milk. In another, a dancing man lifts his arms against the textured grey of elephant skin. And in a third, stacks of colored buckets and a pink tinted hand wrestle with a bold red and yellow backdrop with one all-seeing eye – while the ultimate meaning is obscure, the colors are screamingly bold. Part of the reason these collages are so effective is that their juxtapositions and recontextualizations all seem plausible within the context of this very strange night, and a number of narrower pages create additional overlaps between the images on different pages, breaking up any semblance of normality even further.

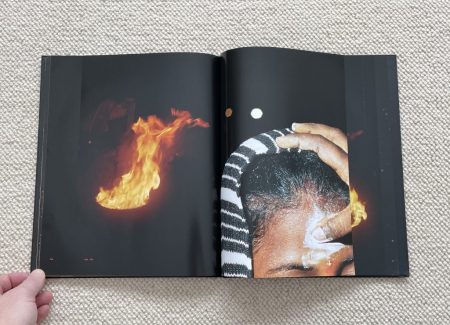

The last section of Afterlife is the most literal, in that it closely follows the episode in the Ramayana when Sita returns from being kidnapped and asks to be tested by fire to prove her purity; she walks through the fire unharmed, thereby verifying her chastity. To mimic that test, Yogananthan creates a sequence of dark images that interleave images of jumping flames with a woman being marked on her forehead with white paint. They are particularly effective, as they come after various scenes of revelers splashing in water or being pounded by waves, the contrast of water and fire made explicit.

Yogananthan’s ability to keep innovating photographically while re-telling this long tale is impressive. This particular installment is darker, moodier, and more deliberately uncertain and visually extreme than the others, but those aesthetic choices match the content of the source material. By continuing to challenge himself, he’s kept us guessing, which has similarly kept us coming back for more. When the seventh and final chapter arrives, we’ll be ready.

Collector’s POV: Vasantha Yogananthan is represented by Jhaveri Contemporary in Mumbai (here) and Polka Galerie in Paris (here). His work has little secondary market history, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.