JTF (just the facts): A total of 64 black-and-white and color photographs, variously framed and matted, and hung against white walls in the main gallery space. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- 17 gelatin silver prints with pencil (from Re-visions), 1978, sized roughly 6×8, 7×9, 16×20 inches

- 3 gelatin silver prints, 1975, 1977, sized 8×10 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print with applied metallic paint, 1974, sized 16×20 inches

- 3 gelatin silver prints with pencil (from See Changes), 1974, sized 16×20 inches

- 2 gelatin silver prints with applied oil pint, 1974, sized 16×20 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print on linen, 1974, sized roughly 50×73 inches

- 4 gelatin silver prints with pencil (from Soho Weekly News), 1980, 1982, sized 14×11 inches

- 3 gelatin silver prints (from See), 1974, sized 16×20 inches

- 3 gelatin silver print diptychs (from Landscape/Loftscape), 1976, each panel sized 16×20 inches

- 3 gelatin silver prints (from Landscape), 1974, 1975, sized 16×20 inches

- 15 gelatin silver prints, mid-1970s, 1978, 1978/2016, 1979, 1979/c2015, 1980, 1980/c2015, 1981, 1981/2016, sized roughly 10×8, 11×14 (or the reverse), 17×14, 20×16 (or the reverse) inches

- 1 gelatin silver print mounted on board, 1968, sized roughly 8×12 inches

- 1 gelatin silver print on RC paper, 1979, sized 8×10 inches

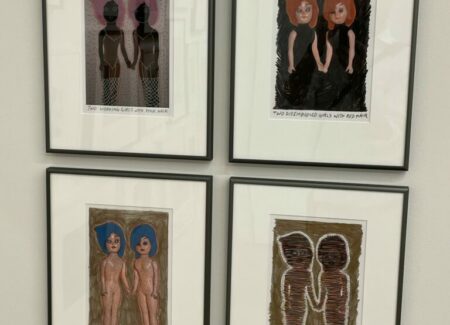

- 4 archival pigment prints with applied oil paint, 2018, sized 10×8 inches

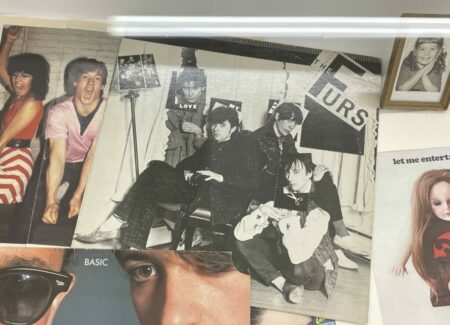

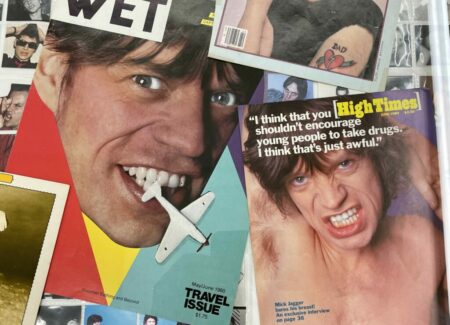

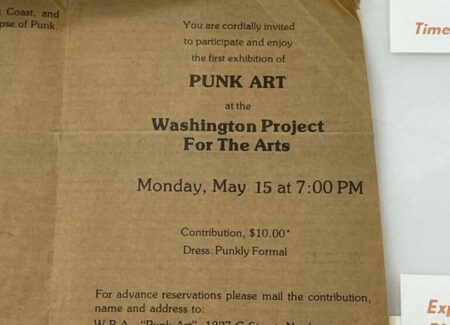

- (2 vitrines): various album covers, newspaper clippings, magazine spreads, exhibition announcements, and other ephemera

A traveling retrospective of Resnick’s work was recently on view at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and the George Eastman Museum. A catalog was published in 2022 to accompany the exhibition (here). (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: As historians and gallerists continue to methodically invest the time and energy required to further fill out the arc of the medium of photography, the last few decades have been sprinkled with plenty of deserving rediscovery stories and the re-emergence of many artists who had previously been overlooked, excluded, or under-appreciated. Over the past decade or so in particular, Marcia Resnick’s star has been on the rise, consistently supported by the efforts of gallery owners Deborah Bell and Paul Hertzmann/Susan Herzig, and culminating last year in Resnick’s first major museum retrospective, which traveled to three venues. This show reprises that retrospective on a smaller scale, slimming the fuller presentation of Resnick’s life’s work down to a densely hung single room arrangement that satisfyingly summarizes the key high points of her photographic career.

Coming out of a run of education at Cooper Union and CalArts in the early 1970s, Resnick took the conceptual and experimental ethos learned in those programs and merged it with the performative energy of the artistic and music scenes found in downtown New York at that time. Over the next decade, Resnick would tap into a flourishing vein of creativity, delivering a half a dozen different photo projects of note, one right after another. Some of her earliest works explored how various overpainting techniques could interrupt the documentary reality of a photograph and introduce other interpretations and memories; in one work, she adds color to a snapshot of her parents in the backyard, and in another, she removes the context surrounding a sleeping girl, leaving her to float in a flat void of metallic silver.

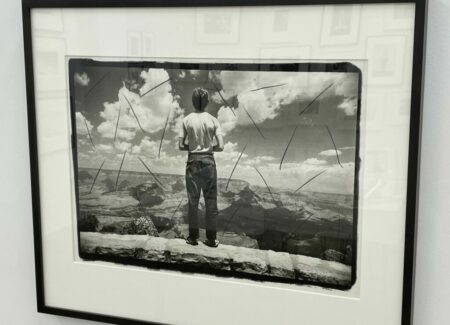

An image Resnick took of classmate (and fellow photographer) James Welling at the Grand Canyon on a road trip back from the West coast in 1973 became the starting point for two projects she worked on in 1974. Welling stands on a stone wall with his back to the camera, interrupting the majestic view of the canyon below and the fluffy cloudscape in the sky. Resnick replayed that pose dozens of times with various other strangers in her project “See”, each subject with his or her back to the camera and facing some landscape or vista, often with the compositional inclusion of a wall, fence, path, staircase, or other barrier to help arrange the frame. The works telescope the seeing (in that we effectively stand behind the featured person, watching them watch the landscape), creating a layered experience that she then multiplied out into a theme and variation exercise. The “See Changes” project returned to the actual Welling image and proceeded to iteratively reinterpret it with drawing, applied graphite, and even the removal of Welling’s figure in a few cases. The examples here get progressively darker, with the pencil markings becoming more densely expressive as the memory becomes more obscure.

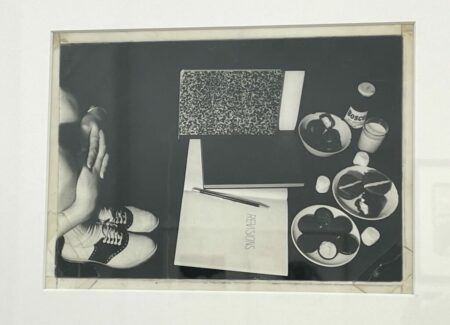

In the mid-1970s, Resnick briefly turned to unpacking the visual frameworks of landscape photography. In her “Landscape” series, she severely unbalances her compositions, giving the land only the tiniest sliver of attention at the bottom of the frame, turning mountains into molehills and leaving expanses of sky to fill the available space; in many ways, it’s an intentional turnabout from the traditional tenets of landscape photography, with its focus on the grandeur of those very same mountains and vistas. Resnick’s “Landscape/Loftscape” diptychs of a few years later are infused with more playful conceptual wit, pairing one image made outside with a second recreation made in her studio. Her tabletop constructions are surprisingly faithful to the original views, their modest materials becoming stand-ins for mountain ranges, boulders, and even discarded tires (which are cleverly represented by chocolate donuts.)

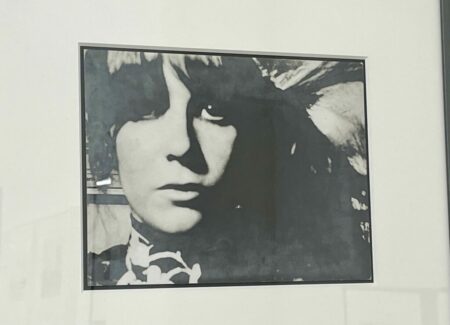

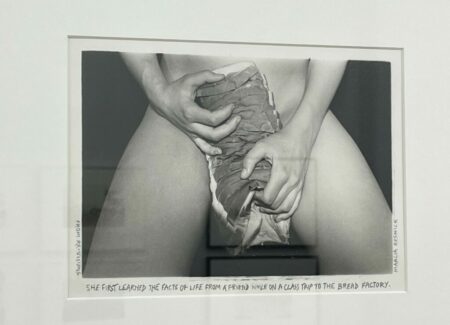

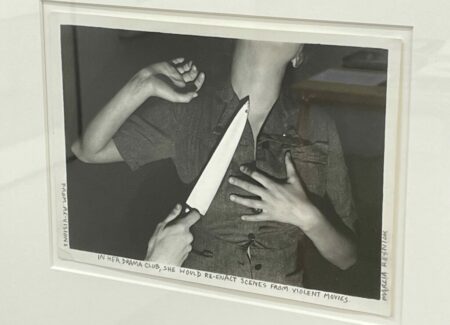

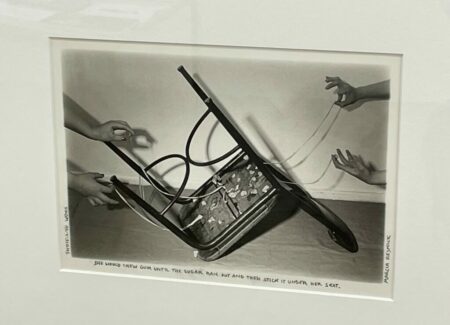

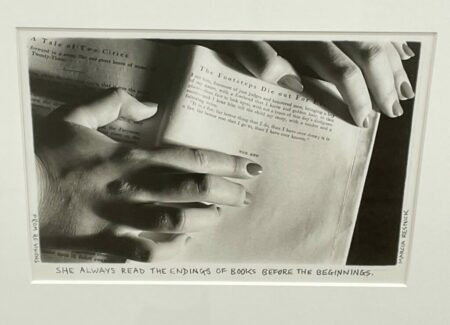

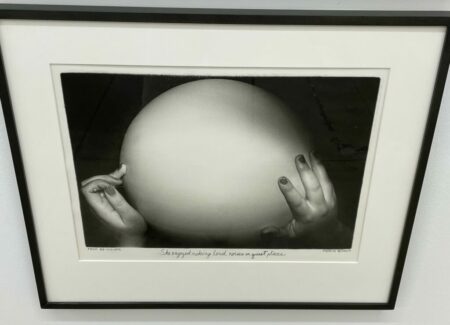

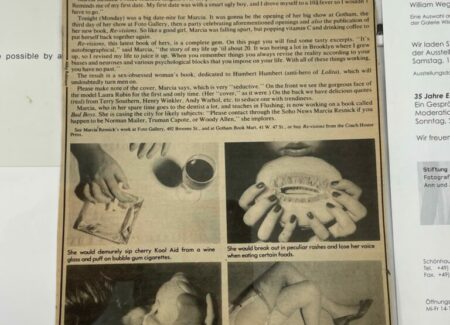

Many of the ideas percolating around in these previous efforts come together in 1978 in “Re-visions”, in what has deservedly become Resnick’s best known project. Having dug into this project at length over the years, in both a previous gallery show (reviewed here) and a re-issued monograph (reviewed here), it’s possible that their subtle provocations and introspective insights (in the context of carefully staged episodes in the life of an adolescent girl) could become too predictable, but seeing more than a dozen prints from the series (in various sizes) here only seemed to reinforce their consistent brilliance and enduring resonance. Each scene was meticulously crafted by Resnick, using a 17-year old model as the protagonist, with text annotations added in pencil to expand on the storytelling possibilities of the images. Her text/image results thrum with visual intelligence, and simmer with the sensual richness of the young woman’s thoughts, impulses, dreams, and surreal obsessions. The “Re-visions” pictures still crackle with wry humor and uneasy energy, adding a more overtly personal voice and performative element to Resnick’s work.

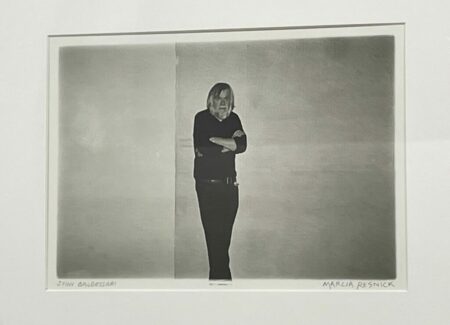

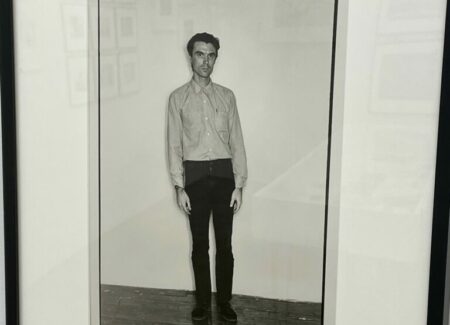

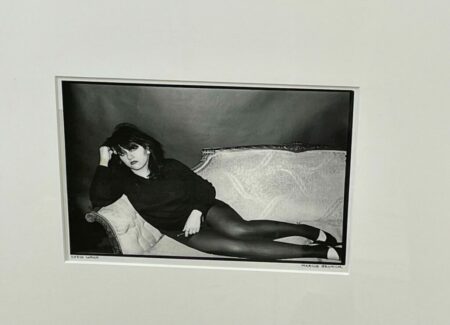

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Resnick turned her attention to portraits, including many of the artists musicians, actors, writers, and other relative celebrities of the downtown scene, while also doing projects for the Soho Weekly News. Her “bad boys” portraits ultimately tallied up at more than 100 individuals, a sampling of which are collected here. David Byrne, Peter Tosh, Johnny Thunders, Iggy Pop, and John Belushi make notable appearances, and there’s even an early self-portrait of Resnick (from 1968) snuck into the mix. Some of these pictures ended up as covers or editorial shoots for SWN, and two overstuffed vitrines gather up some of this material, including images which became album covers, a handful of her “Resnick’s Believe-It-or-Not” scenes (including the classic “Persistent Pony Tails”), and an invitation to a party with the suggested dress code of “punkly formal”.

While those that have been following Resnick’s re-invigorated career over the past decade will find much that they have seen before in this show, the tight edit here creates a succinct introductory sampler that makes a persuasive argument for Resnick’s ongoing artistic relevance. Seeing this survey of her work from the 1970s and 1980s (along with a handful of recent pieces from the past few years which find her returning to overpainting), what stands out is Resnick’s commitment to conceptual experimentation and her sharp sense of inventiveness and wordplay. These two come together in a unique style of shrewd artistic banter, layering artistic playfulness on top of incisive thinking like a well paired double feature.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show range in price from $3000 to $18000. Resnick’s work has little secondary market history, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.